Do Dietary Habits Affect Sinonasal and Respiratory Health?

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the association between diet and respiratory health, including allergic disease, rhinitis, and asthma.

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the association between diet and respiratory health, including allergic disease, rhinitis, and asthma. A growing body of evidence suggests that certain dietary habits are associated with favorable respiratory health, while other dietary habits have a detrimental effect.

Most studies exploring the effects of diet on asthma, allergies, and rhinitis have originated in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Dietary traditions and movements—including low-carb, vegan, and modified Mediterranean diets—have all reportedly led to some reduction in frequency and severity of rhinosinusitis symptoms, with variable results. Reports from some parts of the world suggested that specific dietary habits in children may be protective (or non-protective) in the development of rhinitis.1-6 Despite minimal published research from the United States, anecdotal evidence suggests that changes in dietary habits may lead to abatement of rhinitis symptoms.

As westernization increases in low-resource countries, traditional diets have shifted toward greater consumption of fast food and other energy-dense, low-cost foods. Fast food intake in Latin America is common in children, particularly adolescents, with nearly 20% reporting eating fast food more than three times per week.4 A study of Latin American children demonstrated that children characterized as high fast-food consumers (i.e., greater than three times per week) and low-fruit consumers had increased risk for recurrent wheezing.1

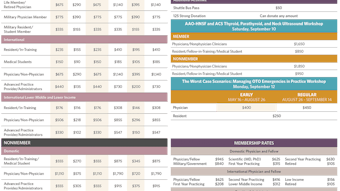

Table. Summary of Dietary Patterns with Observed Effect on Respiratory Health

Table. Summary of Dietary Patterns with Observed Effect on Respiratory Health

Studies in Europe pointed to the Mediterranean diet as protective against allergic rhinitis (AR) with modest protection for wheezing and atopy; in particular, intake of common fruits such as grapes, oranges, apples, and fresh tomatoes showed no association with atopy but were protective against wheezing and AR.5 Of note, the Western diet consisting of red and processed meats, high-fat dairy products, and low vegetable intake contradicts the tenets of a whole food, Mediterranean diet.6 The risk of RCJ was found to be three times higher in children who consumed animal fats more often than three times per week compared to children who consumed animal fats one to two times per week or not at all.3

Cross-sectional studies in Italy and England demonstrate that intake of vegetables, tomatoes, and fresh fruit rich in vitamin C were protective factors for wheezing symptoms and found to be positively associated with ventilatory function, with an even stronger association among children with a history of wheezing.5,7 Furthermore, similar evidence in European countries suggests a strong positive association with rhinitis and other allergic symptoms in children eating candies and lollipops more than three times per week.3

Comparable associations have also been found in Asian countries, relating certain dietary patterns and the frequency and severity of allergic symptoms and rhinitis. With grains as a primary staple in most Asian diets, rice consumption more than three times per week has been associated with reduced risk of rhinitis.2

A study of primary school children in Hong Kong found that a dietary pattern of legumes, butter, nuts, and potatoes was associated with a significantly increased risk of rhinitis.2 Leguminous crops have been considered a source of IgE-mediated allergic sensitivity in both Mediterranean and Asian countries. As such, proposed mechanisms of this immunologic pathogenesis include cross reactivity among different legumes and other allergens. A high intake of saturated fatty acids may ultimately influence arachidonic acid in cell membranes, affecting lymphocyte function and bronchial reactivity.2

The contribution of greater intake of fruits and vegetables to a decreased prevalence of sinonasal and respiratory disease may derive from the role of oxidative stress, which contributes to inflammatory processes in the clinical expression of asthma and other allergic conditions.5-7 Further, the growth of airways during childhood may be vulnerable to oxidative exposures and thus suboptimal antioxidant intake during this critical period may result in oxidative airway damage, reductions in airway compliance, or both.5 Consequently, fruits and vegetables rich in antioxidant vitamins and flavonoids help reduce and modulate both airway and allergic disease. Additionally, high dietary intake of certain omega-3 fatty acids are associated with decreased risk of AR and an inverse association with allergic sensitization.8

From a microbiological standpoint, a study has shown that, relative to industrially produced products, organically derived foods may protect against the risk of asthma and allergies.4 Moreover, fruits and vegetables are densely covered with microbes, and the existence of this ubiquitous plant microbiota has been a subject of recent interest.9 It is theorized a low gut microbiota may be linked to diminished respiratory and allergic health in children and that a rich microbiota facilitated by freshly produced plant-based foods may reduce those outcomes.4,10,11 Additionally, as frequent colonization of S. aureus occurs in the nasal cavity, staphylococcal enterotoxin B has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of food allergy and, subsequently, allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis.12-14 Involuntary ingestion of these bacterial by-products may lead to an immunologic cascade that induces AR via IgE-mediated mechanisms.13,15-23 This may explain the presence of large amounts of IgE antibodies to Staphylococcus enterotoxins in patients with persistent AR and suggests that immunomodulation contributes to the pathogenesis of AR via sensitization of the upper airway.12,13,15,16,23-25 Moreover, the presence of Th1/Th17 inflammation of the sinonsal mucosa may facilitate colonization of unfavorable, dysbiotic microbial flora.26 Patients with chronic sinonasal inflammation may plausibly benefit from dietary modifications as an adjunct to existing medical therapy.

In conclusion, a limited but growing body of evidence suggests that dietary habits influence health beyond the widely known effects on body mass and the digestive and cardiovascular systems. As clinicians, otolaryngologists share a responsibility to educate patients on the benefits of sound dietary habits. This encompasses respiratory and sinonasal health as well as other systemic benefits. Given the substantial consumption of healthcare resources stemming from management of sinonasal and allergic disease, clinicians who evaluate and treat these conditions may consider incorporating dietary history into their clinical encounters. This additional information would enable the clinician to suggest modifications that may yield a complementary benefit in overall health while providing comprehensive otolaryngologic care.

![03 Bites Better Hearing And Speech Graphic [converted]](https://img.ascendmedia.com/files/base/ascend/hh/image/2022/04/03_Bites_Better_Hearing_and_Speech_graphic__Converted_.6268225925563.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=191&q=70&w=340)