Out of Committee: Lassa Fever and Tuberculosis in ENT Practice in Africa

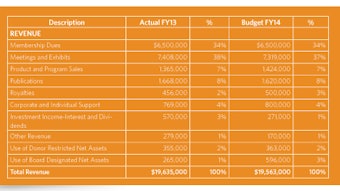

Titus S. Ibekwe, MD, FWAC, University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Abuja, Nigeria Segun Segun-Busari, MD, FWACS, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria Tulio A. Valdez, MD, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Simsbury, CT Our awareness of a certain pathogen as a possible etiology for an otolaryngological (ENT) problem depends on how prevalent this pathogen is in the region where we practice. In ENT practice in Africa, it is important to be aware of the manifestations of infectious diseases, which may not be as common in other places in the world. Lassa fever (LF) and tuberculosis (TB) are common diseases in Africa with well-known otolaryngological manifestations. Lassa Fever LF is an acute arenaviral hemorrhagic infection transmitted by Mastomys natalensis (multimammate rat) prevalent in West African sub-region. It is highly contagious via the droppings and urine of the host carrier. LF can also be transmitted through airborne particles and contact with body fluids of infected humans. There have been reported cases of nosocomial, hospital-acquired infection, transmission from contaminated medical equipment, and other inanimate objects.1 Lassa virus can generate exaggerated immune responses, involving high titres of IgG and IgM.2 The resultant autoimmune responses culminate in loss of cochlear hair cells during the convalescent phase. Direct invasion of the spiral ganglion may result in the loss of integrity of the vestibulocochlear nerve.3 All these pathogenic processes occur during the acute phase of viral infection resulting in sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). About 57 percent to 60 percent of patients recover spontaneously during convalescence.4 The mode of presentation of LF is non-specific, hence the difficulty in clinical diagnosis (Table 1). The classical modes of presentation include high-grade fever >38°C, sore throat, retrosternal pain, cough, odynophagia, conjunctivitis, petechial hemorrhages, abdominal pains, vomiting, and diarrhea. Neurological symptoms (tremors, convulsions, meningitis symptoms, etc.) are not commonly present at this early stage, however SNHL is sometimes present. Recent research suggests that early SNHL and other CNS features predict a poor prognostication.5 Diagnosis is commonly made via ELISA (sensitivity 57 percent and specificity 77 percent6) and confirmed by Lassa Virus-PCR. Ribavirin remains the drug of choice for the management of LF and is efficient when commenced within the first week of active infection. Tuberculosis Africa is currently home to 11 percent of the world’s population, however it carries 29 percent of the global burden of tuberculosis cases and 34 percent of related deaths. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the average incidence of tuberculosis in African countries more than doubled between 1990 and 2005, while throughout the world the incidence remained stable or declined.7 Tuberculosis, an aerosol-transmitted communicable disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 1), primarily affects the lungs. Extrapulmonary TB involves the ear, nose, and throat, lymph nodes, the brain, kidneys, bones, etc. A single cough can produce 3,000 infectious droplet nuclei.8 The size of the infecting tubercle bacilli and the immune status of the host determine the risk of progression from infection to disease. Hence, HIV infection remains the most common single predisposition to TB. Primary tuberculosis of the external ear is not uncommon. Tuberculosis of the middle ear, usually in coexistence with miliary pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), is characterized by painless otorrhea, abundant granulation tissue, multiple tympanic perforations, bone necrosis, and severe hearing loss. However, most of our patients present with the first two clinical features. Our experience showed that otogenic complications such as facial palsy and SNHL appear more frequently in tuberculous otitis patients than in cholesteatoma. The laryngeal tuberculosis is a complication of PTB, which develops as infiltrates and curdled disintegration of tubercles presenting as ulcers with pharyngalgia and (cough) tussis. Tussis is not a characteristic attribute of laryngeal tuberculosis as it depends on changes in the lungs. Lesions of the vocal folds manifest as hoarseness, hyperemia, thickening, and infiltration. The changes are mainly present in the posterior third of the folds. There is characteristic ulceration on the superior surface due to pooling of mycobacterium-laden fluid around the arytenoids during sleep. Tubercular involvement of the nose is rare and is usually secondary to primary PTB.9 It is even more rare to see a case of nasal tuberculosis with simultaneous involvement of the lymph nodes without primary involvement of the lungs. Nasal and sinus tuberculosis remains silent and asymptomatic until well advanced. Patients with nasal tuberculosis usually present with nasal obstruction and discharge. Other symptoms include nasal discomfort, epistaxis, crusting, post-nasal drip, ulceration, recurrent polyps, and sometimes eye symptoms from nasolacrimal duct blockage. Nasal tuberculosis occurs in patients older than 20 years and women are affected more than men by a margin of 3:1.10 It is important to consider nasal tuberculosis in differential diagnosis. An outline on the mode of presentation is shown in Table 1. The quest to exclude malignancy may lead to unacceptable delays in treatment. The diagnosis of nasal tuberculosis is based on: histological identification of granulomatous inflammation (Figure1); positive testing for acid-alcohol resistant bacilli; and positive culture. Newer diagnostic tests have the advantage of speed and improved accuracy, but are not as yet completely evaluated for the diagnosis of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis.11 Several standard anti-Koch’s regime have been proposed with duration of therapy ranges between six and 12 months. Acknowledgement: We thank Farrel J. Buchinsky, MD, chairman, Infectious Disease Committee, AAO-HNS, for editing this article and all the members of the committee for their support. References Inegbenebor U, Okosun J, Inegbenebor J. Prevention of Lassa Fever in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104(1):51-54. Emmerich P, Günther S, Schmitz H. Strain-specific antibody response to Lassa virus in the local population of west Africa. J Clin Virol. 2008;42(1):40-44. Buchman CA, Levine JD, Balkany TJ. In: Essential Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery. Lee KJ, editor. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2003. Infections of the ear; pp. 462-511. Okokhere PO, Ibekwe TS, Akpede GO. Sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever: two case reports. J Med Case Report. 2009; 3: 36. Ibekwe TS, Okokhere PO, Asogun D, Blackie FF, Nwegbu MM, Wahab KW, Omilabu SA, Akpede GO. Early-onset sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(2):197-201. Ibekwe TS, Nwegbu MM, Asogun D, Adomeh DI, Okokhere PO. The sensitivity and specificity of Lassa virus IgM by ELISA as screening tool at early phase of Lassa fever infection. Niger Med J. 2012;53(4):196-199. WHO report 2007: global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. (WHO/HTM/TB/2007.376.) Bates JH, Stead WW. The history of tuberculosis as a global epidemic. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77(6):1205-1217. Harries AD, Dye C: Tuberculosis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100(56):41531. Abebe M, Doherty M, Wassie L, Demissie A, Mihret A, Engers H, Aseffa A. TB case detection: can we remain passive while the process is active? Pan African Med J. 2012;11:50. Masterson L, Srouji I, Kent R, Bath AP. Nasal tuberculosis—an update of current clinical and laboratory investigation. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125(2):210-213.

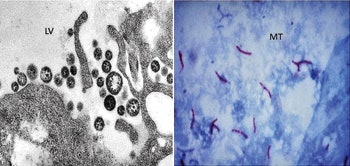

Figure 1, Micrograph Lassa Virus (LV) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT).

Figure 1, Micrograph Lassa Virus (LV) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT).Titus S. Ibekwe, MD, FWAC, University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Abuja, Nigeria

Segun Segun-Busari, MD, FWACS, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria

Tulio A. Valdez, MD, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Simsbury, CT

Our awareness of a certain pathogen as a possible etiology for an otolaryngological (ENT) problem depends on how prevalent this pathogen is in the region where we practice. In ENT practice in Africa, it is important to be aware of the manifestations of infectious diseases, which may not be as common in other places in the world. Lassa fever (LF) and tuberculosis (TB) are common diseases in Africa with well-known otolaryngological manifestations.

Lassa Fever

LF is an acute arenaviral hemorrhagic infection transmitted by Mastomys natalensis (multimammate rat) prevalent in West African sub-region. It is highly contagious via the droppings and urine of the host carrier. LF can also be transmitted through airborne particles and contact with body fluids of infected humans. There have been reported cases of nosocomial, hospital-acquired infection, transmission from contaminated medical equipment, and other inanimate objects.1

Lassa virus can generate exaggerated immune responses, involving high titres of IgG and IgM.2 The resultant autoimmune responses culminate in loss of cochlear hair cells during the convalescent phase. Direct invasion of the spiral ganglion may result in the loss of integrity of the vestibulocochlear nerve.3 All these pathogenic processes occur during the acute phase of viral infection resulting in sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). About 57 percent to 60 percent of patients recover spontaneously during convalescence.4

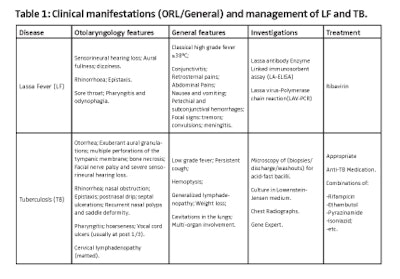

The mode of presentation of LF is non-specific, hence the difficulty in clinical diagnosis (Table 1). The classical modes of presentation include high-grade fever >38°C, sore throat, retrosternal pain, cough, odynophagia, conjunctivitis, petechial hemorrhages, abdominal pains, vomiting, and diarrhea. Neurological symptoms (tremors, convulsions, meningitis symptoms, etc.) are not commonly present at this early stage, however SNHL is sometimes present. Recent research suggests that early SNHL and other CNS features predict a poor prognostication.5 Diagnosis is commonly made via ELISA (sensitivity 57 percent and specificity 77 percent6) and confirmed by Lassa Virus-PCR. Ribavirin remains the drug of choice for the management of LF and is efficient when commenced within the first week of active infection.

Tuberculosis

Africa is currently home to 11 percent of the world’s population, however it carries 29 percent of the global burden of tuberculosis cases and 34 percent of related deaths. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the average incidence of tuberculosis in African countries more than doubled between 1990 and 2005, while throughout the world the incidence remained stable or declined.7

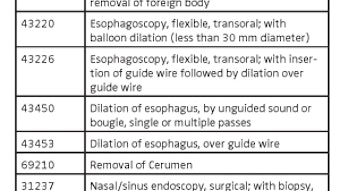

Tuberculosis, an aerosol-transmitted communicable disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 1), primarily affects the lungs. Extrapulmonary TB involves the ear, nose, and throat, lymph nodes, the brain, kidneys, bones, etc. A single cough can produce 3,000 infectious droplet nuclei.8 The size of the infecting tubercle bacilli and the immune status of the host determine the risk of progression from infection to disease. Hence, HIV infection remains the most common single predisposition to TB. Primary tuberculosis of the external ear is not uncommon. Tuberculosis of the middle ear, usually in coexistence with miliary pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), is characterized by painless otorrhea, abundant granulation tissue, multiple tympanic perforations, bone necrosis, and severe hearing loss. However, most of our patients present with the first two clinical features. Our experience showed that otogenic complications such as facial palsy and SNHL appear more frequently in tuberculous otitis patients than in cholesteatoma.

The laryngeal tuberculosis is a complication of PTB, which develops as infiltrates and curdled disintegration of tubercles presenting as ulcers with pharyngalgia and (cough) tussis. Tussis is not a characteristic attribute of laryngeal tuberculosis as it depends on changes in the lungs. Lesions of the vocal folds manifest as hoarseness, hyperemia, thickening, and infiltration. The changes are mainly present in the posterior third of the folds. There is characteristic ulceration on the superior surface due to pooling of mycobacterium-laden fluid around the arytenoids during sleep.

Tubercular involvement of the nose is rare and is usually secondary to primary PTB.9 It is even more rare to see a case of nasal tuberculosis with simultaneous involvement of the lymph nodes without primary involvement of the lungs. Nasal and sinus tuberculosis remains silent and asymptomatic until well advanced.

Patients with nasal tuberculosis usually present with nasal obstruction and discharge. Other symptoms include nasal discomfort, epistaxis, crusting, post-nasal drip, ulceration, recurrent polyps, and sometimes eye symptoms from nasolacrimal duct blockage. Nasal tuberculosis occurs in patients older than 20 years and women are affected more than men by a margin of 3:1.10 It is important to consider nasal tuberculosis in differential diagnosis. An outline on the mode of presentation is shown in Table 1. The quest to exclude malignancy may lead to unacceptable delays in treatment. The diagnosis of nasal tuberculosis is based on: histological identification of granulomatous inflammation (Figure1); positive testing for acid-alcohol resistant bacilli; and positive culture. Newer diagnostic tests have the advantage of speed and improved accuracy, but are not as yet completely evaluated for the diagnosis of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis.11 Several standard anti-Koch’s regime have been proposed with duration of therapy ranges between six and 12 months.

Acknowledgement: We thank Farrel J. Buchinsky, MD, chairman, Infectious Disease Committee, AAO-HNS, for editing this article and all the members of the committee for their support.

References

- Inegbenebor U, Okosun J, Inegbenebor J. Prevention of Lassa Fever in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104(1):51-54.

- Emmerich P, Günther S, Schmitz H. Strain-specific antibody response to Lassa virus in the local population of west Africa. J Clin Virol. 2008;42(1):40-44.

- Buchman CA, Levine JD, Balkany TJ. In: Essential Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery. Lee KJ, editor. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2003. Infections of the ear; pp. 462-511.

- Okokhere PO, Ibekwe TS, Akpede GO. Sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever: two case reports. J Med Case Report. 2009; 3: 36.

- Ibekwe TS, Okokhere PO, Asogun D, Blackie FF, Nwegbu MM, Wahab KW, Omilabu SA, Akpede GO. Early-onset sensorineural hearing loss in Lassa fever. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(2):197-201.

- Ibekwe TS, Nwegbu MM, Asogun D, Adomeh DI, Okokhere PO. The sensitivity and specificity of Lassa virus IgM by ELISA as screening tool at early phase of Lassa fever infection. Niger Med J. 2012;53(4):196-199.

- WHO report 2007: global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. (WHO/HTM/TB/2007.376.)

- Bates JH, Stead WW. The history of tuberculosis as a global epidemic. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77(6):1205-1217.

- Harries AD, Dye C: Tuberculosis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100(56):41531.

- Abebe M, Doherty M, Wassie L, Demissie A, Mihret A, Engers H, Aseffa A. TB case detection: can we remain passive while the process is active? Pan African Med J. 2012;11:50.

Masterson L, Srouji I, Kent R, Bath AP. Nasal tuberculosis—an update of current clinical and laboratory investigation. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125(2):210-213.