Not All Facial Palsy Is Bell’s Palsy

Otolaryngologists may be a last line of defense in the diagnostic workup that can differentiate between Bell’s palsy and other causes of facial palsy.

G. Nina Lu, MD, member of the Committee on Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

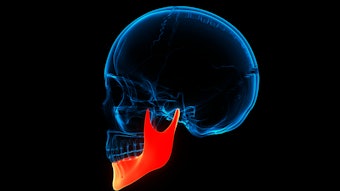

Facial palsy patients often present to otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons for evaluation, many being labeled with a presumptive diagnosis of “Bell’s palsy.” This is the appropriate diagnosis for the majority of facial palsy patients, as Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis. The incidence is around 23 per 100,000 people per year, or about 1 in 60 to 70 people in a lifetime. It affects men and women equally, with a peak incidence between the ages of 10 and 40 and occurs with equal frequency on the right and left sides of the face.1 As specialists of the head and neck, otolaryngologists are responsible for identifying the less common causes of facial palsy and catching when patients deserve further diagnostic evaluation and treatment to differentiate from Bell’s palsy. The AAO-HNSF Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell’s Palsy, published in 2013, serves as an excellent resource.2

It is critical for otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons to have a firm grasp on which facial palsy patients are unlikely to have routine Bell’s palsy and merit additional clinical studies to establish the correct diagnosis. Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. There is currently no confirmatory test for Bell’s palsy, but these patients fit into a well-defined clinical picture.

Patients with Bell’s palsy present with a history of rapid onset, unilateral palsy affecting all branches of the facial nerve equally and progressing to completion within 72 hours. Patients commonly experience ipsilateral periauricular pain, hyperacusis, and alterations in taste. Symptoms and findings deviating from this presentation should prompt immediate consideration for alternate diagnoses.

In addition to a comprehensive history and physical exam, patients should be specifically asked about and examined for hearing loss, vertigo, rash, facial or oral swelling, cranial nerve deficits, facial numbness, myalgia/arthralgia, a history of head and neck cancer (cutaneous and parotid sites in particular), and travel to Lyme endemic areas. In the United States, northeast states, Minnesota, and Wisconsin have the highest incidences of Lyme disease.3

Bell’s palsy can present similarly to Lyme-associated facial palsy. Testing is recommended in Lyme endemic areas as the initial treatment algorithm, even in the absence of reported tick bite. In other parts of the country, a history of travel with outdoor exposure in a Lyme endemic area should prompt consideration for serologic testing as well.

Even in patients who present with classic, rapid onset facial palsy, the expected timeline of recovery is a critical component to confirm the diagnosis. Importantly, patients with Bell’s palsy should show evidence of facial movement by three to four months after onset. It is highly unusual to show no signs of recovery by four to six months post-palsy. Even in a patient with classic symptoms at onset, lack of recovery by four to six months should prompt additional workup.

Dedicated, contrast-enhanced, fine cut imaging of the entire course of the facial nerve should be performed for patients with an initial presentation consistent with Bell’s palsy but who fail to show some recovery of movement by four months. MRI IAC may elucidate findings of facial nerve tumors, such as hemangioma or facial schwannoma, and MRI of the parotid bed helps to evaluate for parotid tumor. If imaging does not reveal abnormality of the facial nerve, nerve exploration with biopsy should be considered.4 Case series in the literature describe carcinoma diagnosed on nerve exploration in the absence of imaging findings, highlighting the importance of nerve biopsy in the diagnostic algorithm for persistent flaccid facial palsy.4-7 In particular, history of regional cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and history of prolonged facial pain were associated with occult malignancy of the facial nerve.5

Recovery of facial function occurs in approximately 70%-85% of cases of untreated Bell’s palsy and up to 94.4% of cases treated with prednisolone within 72 hours of symptom onset.8,9 Minor and major persistent facial dysfunction occurs in 13% and 16% of untreated patients, respectively.10 Post-facial palsy syndrome can arise over 12 months after facial nerve injury and present with synkinesis, hyperkinesis, and lacrimal gustatory dysfunction.10 The prolonged timeline of presentation highlights the importance of routine follow-up of these patients as these symptoms are treatable with a combination of facial neuromuscular retraining, chemodenervation, and, in some cases, surgical myectomy and neurectomy. Referral to a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon is warranted for those patients seeking treatment of facial palsy.

Recurrent ipsilateral or contralateral Bell’s palsy occurs in about 6.5% of patients with a range of 0.8% to 19.5%.11 This differs from a situation of synchronous bilateral facial palsy. Synchronous, bilateral facial palsy occurs when facial paralysis of each side occurs within 30 days of onset. This should prompt an immediate workup for systemic causes of facial palsy such as, but not limited to, Lyme disease, Guillain-Barre syndrome, central nervous system leukemia, human immunodeficiency virus infection, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, infectious mononucleosis, and neurodegenerative disease.12 A referral to neurology and rheumatology colleagues should be considered as well.

The term “Bell’s palsy” may be used erroneously to refer to all forms of facial palsy, but it does represent one diagnosis among many for the patient with unilateral facial weakness. Otolaryngologists may be a last line of defense in the diagnostic workup that can differentiate between Bell’s palsy and other causes of facial palsy that are more ominous.

References

- Victor M, Martin J. Disorders of the cranial nerves. In: Isselbacher KJ, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 1994: 2347-2352.

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(3 suppl):S1-S27. doi:10.1177/0194599813505967

- Lyme Disease Data Surveillance Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 27, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/surveillance-data.html

- Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010 Sep-Oct;31(5):339-42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003. Epub 2009 Jun 24. PMID: 20015776.

- Boahene DO, Olsen KD, Driscoll C, Lewis JE, McDonald TJ. Facial nerve paralysis secondary to occult malignant neoplasms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):459-465. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2003.12.013

- Mandava S, Gutierrez CN, Oyer SL. Persistent Facial paralysis diagnosed as “Bell’s palsy.” Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. Published online August 11, 2023. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2023.0100PMID: 37566521.

- Chung EJ, Matic D, Fung K, et al. Bell’s palsy misdiagnosis: characteristics of occult tumors causing facial paralysis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;51(1):39. Published online October 18, 2022. doi:10.1186/s40463-022-00591-9

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;(549):4-30. PMID: 12482166.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1598-1607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072006

- Peitersen E. Natural history of Bell’s palsy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1992;492:122-124. doi:10.3109/00016489209136829

- Dong SH, Jung AR, Jung J, et al. Recurrent Bell’s palsy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2019;44(3):305-312. doi:10.1111/coa.13293

- Gaudin RA, Jowett N, Banks CA, Knox CJ, Hadlock TA. Bilateral facial paralysis: a 13-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(4):879-887. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002599