Completing the Care Cycle in the Adult Patient with Cleft Lip–Palate

The otolaryngology-head and neck surgeon is well suited to address the unique unmet needs of these patients.

David A. Shaye, MD, MPH, Krishna G. Patel, MD, PhD, and Travis T. Tollefson, MD, MPH, Chair, Otolaryngology Cleft and Craniofacial Committee

A child born with a cleft lip–palate in the United States receives comprehensive cleft care in a multidisciplinary clinic until young adulthood. The specialty of otolaryngology is integral to this care, with expertise in the communication sciences of hearing and speech, maxillofacial reconstruction, and soft tissue surgery.

Across the U.S. and Canada there are 197 accredited, multidisciplinary cleft lip and palate programs providing a graduated approach to cleft lip–palate care from birth to adulthood. For a variety of reasons, young adults commonly exit the care pathway prior to completing the available treatments. Patients may have poor access to a multispecialty cleft team and miss certain key surgical steps such as bone grafting or rhinoplasty. Other returning adult patients, having reached their allostatic load of repeated examinations, interventions, and surgeries as teenagers, become psychologically ready to revisit their cleft care as an adult. Some adult cleft patients immigrate to the U.S. from regions with less access to care. Despite the cause, there remains a need for adult cleft care, and otolaryngologists are key to addressing this gap.

Cleft Lip Deformity

When we communicate, the nose and lips are an area of focus second only to the eyes. Stigmata of the congenital cleft lip deformity can continue to cause undue psychosocial distress and discrimination well into adulthood. Surgical treatment for the adult cleft patient is grounded in a solid foundation in primary cleft lip techniques. The surgical goal is to establish the concentric muscular sling of the mouth with a symmetric Cupid’s bow structure and establish natural lip volume and a concealed scar. Cleft surgeons draw on a variety of repair techniques, such as the rotation-advancement flap, subunit repair, and other geometrically designed repairs to improve the scar and bring the Cupid’s bow into anatomical alignment.

Lip volume and contour is an important consideration in the adult cleft patient. Fat transfer, fascia, and dermal grafts expand the armamentarium of the otolaryngologist whose training included wedge resections and reconstructions for cutaneous cancers. Injectable hyaluronic acid fillers are popular and may offer a “trial run” for adding volume to areas such as a depressed cleft lip scar. However, while filler can be very effective, it must be repeated to maintain the result and introduces some scarring and foreign material into a potential surgical site. Informed consent should contrast the relative ease and costliness of filler treatment with more definitive and economical surgical options.

Management of the poorly scarred lip is an important aspect of cleft care in adult and pediatric populations alike. Adult cleft lip scar camouflage techniques may treat depressed, red, or misaligned scars, with an eye toward makeup application and facial hair patters. Laser, dermabrasion, steroid injections, and medical tattooing may provide nuanced nonsurgical options. The severely scarred lip may require a surgeon adept at more complex reconstructive designs, such as an Abbe flap, to restore contour.

Cleft Nasal Deformity

Nasal symmetry and relief of nasal obstruction are equally important to the adult cleft patient. Reversing the effects of congenital deformational forces on the nose is a formidable challenge to even the most experienced rhinoplasty surgeon. Recognition of these sequelae and proper referral to a surgeon who is experienced with rhinoplasty are often the most helpful contributions to the patient with a cleft nasal deformity.

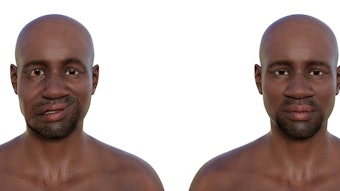

Figure 1. Adult patient with cleft lip nasal deformity before and after definitive septorhinoplasty.

Figure 1. Adult patient with cleft lip nasal deformity before and after definitive septorhinoplasty.

Figure 2. Adult patient with cleft lip nasal deformity from base view.

Figure 2. Adult patient with cleft lip nasal deformity from base view.

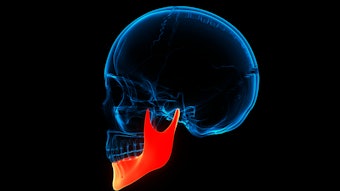

The cleft nasal deformity is often the most outwardly perceived sign of a cleft. A diverse set of cartilages and a skin-soft tissue envelope drape over dentofacial structures that are frequently undertreated. The ala of the cleft side is laterally, inferiorly, and posteriorly displaced, with poor nasal tip (dome) height. Three-dimensional computed tomography illustrates how the alveolar bone cleft results in a lack of skeletal foundation to the nasal base. Skills in the grafting of bone, cartilage, and skin are needed to achieve the desired aesthetic and functional nasal outcomes. Working together with maxillofacial (orthognathic) surgery allows for corrections to dental occlusion and the greater facial skeletal.

Figure 3. 3-D CT scan of adult patient with unilateral cleft showing unrepaired alveolar cleft and dental malocclusion that was never addressed as a child.

Figure 3. 3-D CT scan of adult patient with unilateral cleft showing unrepaired alveolar cleft and dental malocclusion that was never addressed as a child.

Figure 4. Video of 3-D CT scan showing orthodontics on an adult patient with right cleft lip showing need for dental restoration and bone grafting.

One of our American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery’s Otolaryngology Cleft and Craniofacial Committee members, Brianne B. Roby, MD, from the University of Minnesota, recently presented her Triological Society thesis on the perceptions of children viewing other children with cleft lip and palate using eye tracking software. These data shed light on lay person observations of cleft lip sequelae and may eventually guide surgeons on when to pursue further treatment.

Nasal obstruction in the adult cleft patient is one of the most frequent reasons to seek care. The caudal septum is deviated to the cleft side because the orbicularis oris muscles were aberrantly attached there at birth. Septoplasty in the patient with a cleft palate must be performed with the knowledge that there is no bony nasal floor, only a mucosal soft tissue bridge over the underlying repaired cleft palate. Endoscopic assistance can be helpful for challenging, posteriorly deviations. An experienced rhinoplasty surgeon with a firm understanding of the underlying congenital deformity can manage expectations and safely address nasal aesthetics and function.

Hearing and Speech

Adult hearing and speech are imperative areas of comprehensive cleft care that lie squarely within otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Infants with cleft palate have a significantly higher risk of eustachian tube dysfunction requiring close audiologic monitoring, tympanostomy tube placement and occasional repair of tympanic membrane perforations, and cholesteatoma treatment.

Adult patients with a history of palatoplasty may present with secondary speech issues that include air leak during velopharyngeal closure, know as velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). The evidence for adult speech surgery to correct VPD is less rigorously studied than in children; rates for a patient to require a secondary speech surgery after primary cleft palate repair approaches 10%-20%. Alternatively, adults with a history of secondary speech surgery as a child may experience worsening sleep apnea with age. Surgical management of VPD and obstructive sleep apnea is a balancing act, and consideration of the risks and benefits of surgical reversal of speech surgery is worthy of detailed discussion. The assistance of specialists with a speech, language, and sleep backgrounds may be helpful.

Otolaryngologists should advocate for adult patients with cleft lip–palate by appropriately referring them to speech and hearing professionals, dental professionals, and other specialty providers within the cleft care pathway. In a recent survey of 63 adult patients with cleft lip–palate, 27% indicated that they were unaware that additional clinical evaluation was an option, while others cited financial barriers as another hurdle (Braun, et al.). Often the most impact we can have on patients is to listen and refer them to the proper specialists within our diverse field and to our colleagues.

Conclusion

Adults with cleft lip and palate have needs that continue well past their teenage years. Surgeons trained in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery are well suited to address the unique unmet needs of these patients. When these patient present to your clinic, consider it an opportunity to identify areas where a holistic approach to their needs can be directed by otolaryngology and involve a multispecialty team. It is deeply rewarding to care for a child born with a cleft lip–palate, and an opportunity to do the same for adult patients is before us.

References

Braun SE, O’Connor MK, Garg RK. Adult cleft patients: an exploration of functional needs and treatment barriers. J Craniofac Surg. 2023;34(1):332-336. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000008931. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35984002

Mcwilliams D, Thornton M, Hotton M, Swan MC, Stock NM. Transitioning from child to adult cleft lip and palate services in the United Kingdom: are the NICE Guidelines reflected in young adults’ experiences? Psychol Health Med. 2023;28(8):2032-2044. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2022.2124291. Epub 2022 Sep 14. PMID: 36106353.