Treatment of Subcondylar Fractures of the Mandible: A Shifting Paradigm

Open reduction with plating outperforms maxillomandibular fixation for displaced subcondylar fractures.

Sam L. Oyer, MD, and Kieran S. Boochoon, MD, for the Committee on Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

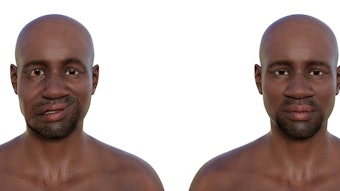

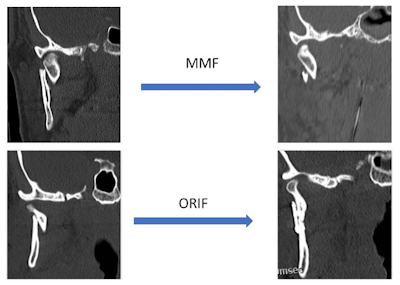

Subcondylar fractures are one of the most common sites for fractures of the mandible, accounting for 20.6% of all mandible fractures.1 These fractures extend from the sigmoid notch through the posterior mandibular ramus below the level of the condylar neck. Traditionally, subcondylar fractures have been managed with closed treatment using a short course of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) rather than open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), which is the mainstay of treatment for fractures in other portions of the mandible. Treatment with MMF, often using elastic bands rather than rigid wires, restores a functional dental occlusion for the patient, while permitting some movement of the temporal mandibular joint (TMJ). Long-term (> 4 weeks), rigid MMF can lead to TMJ ankylosis and should be avoided.2 True bony reduction of the fracture is not typically achieved with MMF treatment alone (Figure 1). Over time and following jaw physiotherapy, the patient’s occlusion can be maintained through retraining the muscles of mastication and possible remodeling of the TMJ itself.

Figure 1. Comparison of bony reduction before and after closed reduction with MMF (top row) and ORIF treatment (bottom row). Note that following MMF treatment, the bony segments remain somewhat displaced despite establishing dental occlusion. In the ORIF treatment, mandibular height has been restored and the fracture has been fully reduced.

Figure 1. Comparison of bony reduction before and after closed reduction with MMF (top row) and ORIF treatment (bottom row). Note that following MMF treatment, the bony segments remain somewhat displaced despite establishing dental occlusion. In the ORIF treatment, mandibular height has been restored and the fracture has been fully reduced.

While closed treatment has been the mainstay for subcondylar fractures, there are some commonly accepted indications for ORIF of these fractures based on the severity of the fracture. Historically, these indications proposed by Zide and Kent included displacement of the condylar segment into the middle cranial fossa, lateral displacement of the capsule out of the glenoid fossa, foreign body present within the fracture, or inability to achieve occlusion with MMF.3

Challenges with ORIF repair of subcondylar fractures center around difficulty with surgical exposure and limited bone stock available for rigid fixation. External approaches to the subcondyle require extensive dissection either through or behind the parotid gland and put the patient at risk for developing facial paralysis from nerve injury or stretch. These limitations have largely driven the practice patterns of managing most subcondylar fractures with MMF rather than ORIF, despite the fact that fractures of essentially all other portions of the mandible are routinely managed with ORIF.

Newer reports have raised some concerns with long-term functional limitations of MMF treatment of subcondylar fractures, including persistent TMJ pain, decreased jaw range of motion, and bite misalignment from loss of vertical mandibular height.4 With increased awareness of the limitations of MMF management for subcondylar fractures, the following updated indications for ORIF of these fractures were proposed: displacement of the bony segments by > 10 degrees, ramus height shortening of > 2 mm, bilateral subcondylar fractures where at least one side should be treated with ORIF, other associated midfacial fractures where reestablishing appropriate facial height is key, or for some edentulous patients who cannot be placed in MMF.5

Mounting evidence suggests that for patients who meet these criteria with significantly displaced, angulated, or foreshortened fractures, improved outcomes may be seen with ORIF compared to MMF. A randomized controlled trial of 40 patients treated with either ORIF or MMF demonstrated improved mouth opening and jaw range of motion along with decreased pain in patients treated with ORIF compared to MMF.6 Multiple additional studies with a variety of methodologies have demonstrated similar findings, and several systematic reviews have been carried out to summarize these findings.7,8 The most recent systematic review from 2023 evaluated 32 studies including 1,010 patients.9 The authors found superior mouth opening and lateral excursion along with decreased rates of malocclusion, chin deviation, and trismus among patients treated with ORIF compared with MMF. One included study also demonstrated better psychosocial well-being among the ORIF group as measured by the FACE-Q quality-of-life instrument.10

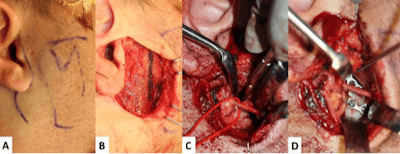

Figure 2. External approach for ORIF of a right subcondylar fracture. Pre-auricular skin incision and surface markings of the mandible are shown (A). After elevating the skin flap, a separate incision in the parotidomasseteric fascia is marked (B). Exposure of the fractured segments through the parotid gland is shown in C with a red vessel loop marking a buccal branch of the facial nerve. After bony reduction and plating the fracture is stabilized with a dynamic 3D plate (D).

Figure 2. External approach for ORIF of a right subcondylar fracture. Pre-auricular skin incision and surface markings of the mandible are shown (A). After elevating the skin flap, a separate incision in the parotidomasseteric fascia is marked (B). Exposure of the fractured segments through the parotid gland is shown in C with a red vessel loop marking a buccal branch of the facial nerve. After bony reduction and plating the fracture is stabilized with a dynamic 3D plate (D).

Studies examining various plating techniques for these fractures are less abundant, but specialized subcondylar plates using a 3-D configuration demonstrate less strain in biomechanical studies compared to a single or two mini-plate system.11 In clinical studies, one mini-plate has also been shown to provide less stability than two mini-plates or a 3-D plate construct.12 Evaluations of the risk of facial nerve weakness following ORIF of subcondylar fractures via a trans-facial approach have included numerous studies and at least two large systematic reviews. Rozeboom, et al. evaluated over 2,700 patients in 70 studies and found a 12% rate of transient weakness, of which 5% resulted in permanent weakness.13 The authors found that a transparotid approach carried a higher rate of transient facial weakness but demonstrated higher rates of recovery with permanent facial weakness seen in 0.07% of patients compared with 0.4% when a retro-parotid approach was used.

Al-Moraissi, et al. evaluated 29 studies including 1,200 patients and found a transient rate of facial paralysis of 11%.14 The authors concluded that encountering the facial nerve during the approach was associated with higher rates of transient but not permanent facial paralysis. Rates of facial paralysis increased as the extent of facial nerve dissection increased; therefore, the authors recommended blunt dissection through the parotid without intentional nerve identification rather than deliberate identification and dissection of the facial nerve.

An alternative to the external approach for ORIF is the transoral, endoscopic approach.15 This has the advantage of avoiding a skin incision and minimizing risk of injury to the facial nerve, but this approach is only suitable for relatively low subcondylar fractures due to limited exposure obtained through the mouth. Plating is performed either with transbuccal trochars, as would be done for angle fractures, or with right angle drills and screw drivers. This approach requires additional instrumentation and is associated with a steep learning curve.

Continual evaluation of patient outcomes is an important part of patient care for every disease process. In the area of subcondylar mandible fracture management, there remains a wide variety of practice patterns along with some controversy over the best treatment strategy. Timing of repair should be carried out as soon as feasible to minimize the duration of pain and discomfort for the patient, yet a delay of several days or even a week is acceptable when needed to triage other associated injuries or refer to the appropriate facility for definitive management. Treatment should be individualized to each patient’s unique fracture pattern, comorbidities, and tolerance of surgical intervention.

For minimally displaced, unilateral fractures with malocclusion, closed treatment with a short course of guiding elastic MMF remains the treatment of choice. For more complicated fractures that are significantly displaced, angulated, foreshortened, bilateral, or associated with other midfacial fractures, however, there is now good evidence that the approach of careful bony reduction and ORIF provides better patient quality-of-life outcomes compared with MMF alone. Patients presenting with these fracture types should be counseled on the risks and benefits of this approach compared to MMF.

Endoscopic, transoral approaches should also be considered in the appropriate patients to further minimize surgical risk, while achieving appropriate ORIF. Referral to a high-volume trauma center with a surgeon who is comfortable with these approaches is appropriate if these surgical treatments are not available in the facility where the patient presents. Continued research and evaluation of patient quality of life is needed in this area to further refine the optimal treatment for these challenging mandibular fractures.

References

- Natu SS, Pradhan H, Gupta H, et al. An epidemiological study on pattern and incidence of mandibular fractures. Plast Surg Int. 2012;2012:834364.

- Hirjak D, Machon V, Beno M, Galis B, Kupcova I. Surgical treatment of condylar head fractures, the way to minimize the postraumatic TMJ ankylosis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2017;118(1):17-22.

- Zide MF, Kent JN. Indications for open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41(2):89-98.

- Bayat M, Parvin M, Meybodi AA. Mandibular subcondylar fractures: a review on treatment strategies. Electron Physician. 2016 Oct 25;8(10):3144-3149

- Ellis E, Kellman RM, Vural E. Subcondylar fractures. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20(3):365-382.

- Singh V, Bhagol A, Goel M, Kumar I, Verma A. Outcomes of open versus closed treatment of mandibular subcondylar fractures: a prospective randomized study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(6):1304-1309.

- Chrcanovic BR. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of mandibular condylar fractures: a meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(2):158-179.

- Al-Moraissi EA, Ellis E. Surgical treatment of adult mandibular condylar fractures provides better outcomes than closed treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(3):482-493

- Shikara M, Bridgham K, Ludeman E, Vakharia K, Justicz N. Current management of subcondylar fractures: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(5):956-969.

- Gibstein AR, Chen K, Nakfoor B, Gargano F, Bradley JP. Mandibular subcondylar fracture: improved functional outcomes in selected patients with open treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(3):398e-406e.

- Darwich MA, Albogha MH, Abdelmajeed A, Darwich K. Assessment of the biomechanical performance of 5 plating techniques in fixation of mandibular subcondylar fractures using finite element analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(4):794.e1-8.

- Marwan H, Sawatari Y. What is the most stable fixation technique for mandibular condyle fracture? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(12):2522.e1-2522.e12.

- Rozeboom AVJ, Dubois L, Bos RRM, Spijker R, de Lange J. Open treatment of condylar fractures via extraoral approaches: a review of complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(8):1232-1240.

- Al-Moraissi EA, Ellis E, Neff A. Does encountering the facial nerve during surgical management of mandibular condylar process fractures increase the risk of facial nerve weakness? A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(8):1223-1231.

- Nam SM, Kim YB, Cha HG, Wee SY, Choi CY. Transoral open reduction for subcondylar fractures of the mandible using an angulated screwdriver system. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75(3):295-301.