Glottic Cancer Transoral CO2 Laser Microsurgery (TOLMS): Current Concepts and Limits

Three variables and their impact on the option of endoscopic laser surgery for primary vocal fold cancer.

Abie H. Mendelsohn, MD, and Marc Remacle, MD, PhD

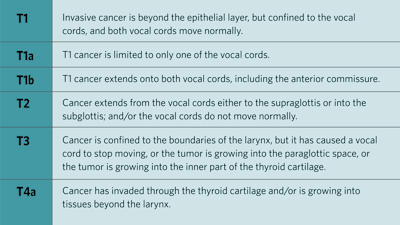

A middle-aged nonsmoking man who works in consulting comes into the office complaining of one month of continuous hoarseness. The resulting laryngeal examination shows an exophytic (superficial) growth limited to a single vocal fold without involvement of the anterior commissure. This patient should enjoy a greater than 98% survival rate and excellent voice quality regardless of which treatment option he would pursue. The two standard-of-care options for this earliest stage glottic carcinoma (T1a) would be either through external beam radiation therapy (XRT) or endoscopic laser surgery. (Table 1 reviews tumor staging of glottic cancers.)

Table 1. AJCC tumor stages of glottic laryngeal cancer.

Source: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Eighth edition. American College of Surgeons; 2018.

Source: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Eighth edition. American College of Surgeons; 2018.

Click here for larger image.

Arguments for transoral CO2 laser microsurgery (TOLMS) is that it is highly precise and allows for the removal of small, targeted areas of tissue with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue. This is important in the treatment of vocal cord cancers because it allows the cancerous tissue to be removed while preserving as much of the patient's normal laryngeal tissues as possible.

In contrast, XRT involves the use of ionizing radiation to destroy cancer cells. Although it is effective at killing cancer cells, this type of treatment can also damage healthy tissue, leading to a range of side effects, including fatigue, skin irritation, and dysphagia. External beam radiotherapy also may not be as precise as laser surgery, meaning that healthy tissue surrounding the cancerous area may also be damaged.

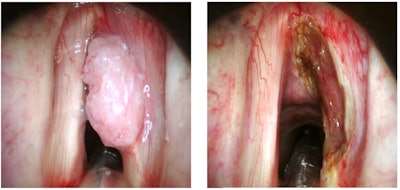

CO2 laser surgery has a shorter recovery time than XRT. This is because the procedure is less invasive and does not involve the use of ionizing radiation, which can cause long-term fatigue and other side effects. This allows patients to return to their normal activities more quickly. As such, this patient undergoes TOLMS with the pre- and postoperative photographs as shown in Figure 1, receiving a type III laser cordectomy as published by the European Laryngological Society (ELS).

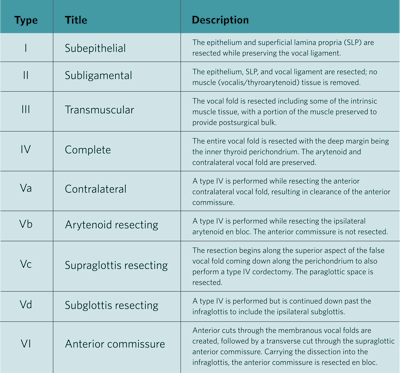

(Table 2 reviews the ELS classification scheme.)

Table 2. European Laryngological Society classification system of cordectomies for glottic cancer.

Source: Remacle, M., Eckel, H., Antonelli, A. et al. Endoscopic cordectomy. A proposal for a classification by the Working Committee, European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257(4):227-231. doi: 10.1007/s004050050228.

Source: Remacle, M., Eckel, H., Antonelli, A. et al. Endoscopic cordectomy. A proposal for a classification by the Working Committee, European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257(4):227-231. doi: 10.1007/s004050050228.

Click here for larger image.

Figure 1. Pre- and postoperative photographs of patient who underwent TOLMS.

Figure 1. Pre- and postoperative photographs of patient who underwent TOLMS.

Photos courtesy of Marc Remacle, MD, PhD.

Yet, there are several clinical scenarios that may lead some clinicians to wonder if endoscopic laser surgery would be a viable option for patients who do not fit the classic presentation above. In this brief review, we will discuss three such variables and their impact on the option of endoscopic laser surgery for primary vocal fold cancer.

Anterior commissure involvement anecdotally was thought to be an argument against endoscopic laser surgery, which has been proven untrue. As compared with cancers that do not involve the anterior commissure, those that do have worse control rates and worse voice quality regardless of the treatment choices. However, several meta-analysis publications have been unable to definitively establish either XRT or endoscopic surgery as a superior option for either outcome measure.

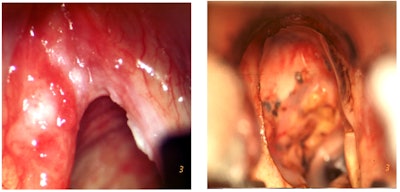

If imaging shows undisturbed thyroid cartilage, patients with T1b cancers can be readily removed using a systematic surgical resection classified as a type VI cordectomy. CO2 laser is used to remove the tumor en bloc by cutting through both anterior vocal folds, and then by cutting around the level of the false vocal folds, the tumor can then be peeled off the inner thyroid cartilage down to the infraglottis. (Figure 2 shows the before and after photos.) Importantly, in the cases of anterior thyroid cartilage invasion, though endoscopic cartilage resection has been described, this upstaging of the tumor to a T3 generally discourages endoscopic surgery as a reliable treatment option.

Figure 2. Before (right) and after (left) photos of tumor peeled off the inner thyroid cartilage down to the infraglottis.

Figure 2. Before (right) and after (left) photos of tumor peeled off the inner thyroid cartilage down to the infraglottis.

Photos courtesy of Marc Remacle, MD, PhD.

Specifically, what are the T stage limits of endoscopic laser surgical resection? From a strictly surgical standpoint, essentially all the earliest stage carcinomas (T1a and T1b) tumors should have endoscopic surgery discussed as a possible treatment option. Second stage cancers, T2, are comprised of a mixed bag of tumor extents. T2 tumors can be upstaged either because of involvement outside the glottis (into the supraglottis or down into the subglottis) or because of limited vocal fold mobility during awake indirect laryngoscopy.

On the face of it, neither factor resulting in a T2 staging presents a limitation for endoscopic laser resection, but both are critical to recognize early to design the correct surgical approach. Tumors with increased bulk or with endophytic growth resulting in sluggish vocal fold mobility can be well managed with ELS cordectomy type III, or even a type IV, providing total removal of the soft tissue of the vocal fold. Similarly, T2 cancers with extension outside the strict confines of the glottis can be addressed via “extended,” or type V, ELS cordectomy. These extended types can also achieve an en bloc resection of tumors either extending up to the supraglottis (type Vc) or down to the subglottis (type Vd). As such, the majority of T2 primary glottic carcinomas should be at the very least offered primary TOLMS along with consideration of primary XRT.

Similar to anterior commissure involvement, common practice is to exclude advanced T stages from TOLMS consideration, but with selected tumors we can see that the potential benefits of primary surgical resection can be even greater than in early staged tumors. Although there are specific and irrefutable contraindications for TOLMS that include extension outside the larynx (i.e., all T4 tumors) or involvement of the cricoarytenoid joint space, once cancer invades the joint space, the deep margin becomes the posterior cricoid cartilage shelf, which is not reliably cleared endoscopically. Therefore, when considering TOLMS for T3 cancers, it is critical to note whether a vocal cord that appears to have lost mobility represents true invasion of the cricoarytenoid joint. Many patients presenting with what ostensibly appears to be “fixed” vocal cords in fact represent bulky tumors that become too cumbersome for the vocal process to displace but do not represent cancer invasion into the joint space. Paraglottic space invasion, which generally is called by a radiologist but is challenging to diagnose clinically, also upstages glottic cancers to T3 advanced staging. However, this lateral space within the confines of the cartilaginous skeleton of the larynx can readily be resected via a type IV ELS cordectomy with excellent oncologic and functional outcomes as compared with similar staged cancers treated with primary XRT.

Professional voice users represent another critical subtopic within the discussion of glottic cancer treatment options. A professional voice user is a general term that broadly describes any individual whose professional function is directly tied with both the volume and quality of voice production. Examples of professional voice users include classroom teachers, trial lawyers, and fitness coaches. This class of patient generally brings a heightened priority to voice conservation when compared with retired individuals or those whose professional productivity is completely independent from their voice quality. Meta-analysis and systematic reviews have consistently demonstrated that voice outcomes following TOLMS is equal at the long-term follow-up mark (at least six to nine months following treatment). As such, those professional voice users who are able to maintain with poor early voice volume and tone for this early recovery period should be strongly encouraged to pursue TOLMS. However, for those professional voice users and the subcategory of vocalists (singers, stage performers), primary XRT should generally be considered as their best option.

As opposed to the voice changes following XRT that can result from diffuse scarring, persistent hoarseness following TOLMS generally stems from either glottic insufficiency or glottic webbing (synechia) along the anterior commissure. Fortunately, both of these sequalae can be addressed. Glottic insufficiency can be treated by vocal fold augmentation, generally through a standard type I medialization thyroplasty. However, importantly providers should wait 12 months at the very least prior to surgically augmenting a vocal fold following TOLMS. Synechia can be treated prophylactically or after the fact. With TOLMS centered along the anterior commissure (i.e., ELS type VI), surgeons may consider placing a silastic keel sutured in place (as described previously by Lichtenberger) at the time of cancer resection. Alternatively, following early observation period, patients may be brought back to the operating room for secondary CO2 laser lysis of the webbing with keel placement. Although not commonly required, surgical interventions for persistent hoarseness are available following TOLMS.

In all, while not all glottic cancers can be treated successfully via TOLMS, a large percentage of patients who do not fit the classic early-stage presentation can still enjoy the benefits of endoscopic surgical resection, including increased precision, shorter treatment times, and shorter treatment recovery times.