From Messerklinger to Kennedy – ONLINE EXCLUSIVE

Nikhila P. Raol, MD While trainees in the modern era of otolaryngology know the endoscopic technique to be the routine approach to sinus surgery, it was not long ago that an open-operative method was the most commonly used technique. Hirschman, in 1901, used a cystoscope to visualize the maxillary sinus through an oroantral fistula, while some years later, in 1922, Spielberg accessed the maxillary sinus using an athroscope via the inferior meatus. However, true advancement in the design of the scopes is what led to the revolution that lay ahead. Born in 1918 in Leicester, England, Harold Hopkins fell into a career in lens making following graduation, due to the limited number of jobs in his hometown. Eventually, he shifted his focus toward fiberoptics, and 1960 he patented the rod-lens system. Finding no takers for his work in Britain or in the United States, he presented his invention at an exhibition in Germany. Through a friend who was present at the exhibition, Karl Storz came to know about the technology and soon after, the Storz-Hopkins endoscopes became reality. Storz astounded the medical community with additional technology, the flexible fiberglass gastroscope, presented by the American gastroenterologist Hirschowitz. Combining these technologies, Storz quickly licensed the concept of a fiberoptic light transmission coupled with the rod-lens system. The advent of this technology made way for the fathers of modern day sinus surgery to implement these new tools in the field of otolaryngology. In the 1970s, Messerklinger used these endoscopes to visualize the mucociliary clearance patterns that ultimately changed the way sinus surgery was viewed, with the natural ostia of the sinuses found to play the most important role in maintaining the health of the sinuses. Because of this discovery, the need for external approaches to the sinuses became nearly obsolete, as the endoscopes became a mainstay of surgery. Another Austrian otolaryngologist, Stammberger, was able to translate these observations and descriptions into English and bring them to the United States via Kennedy at Johns Hopkins. By partnering further with Storz, these exceptional surgeons turned endoscopic sinus surgery into what it is today: an art form.

Nikhila P. Raol, MD

While trainees in the modern era of otolaryngology know the endoscopic technique to be the routine approach to sinus surgery, it was not long ago that an open-operative method was the most commonly used technique.

Hirschman, in 1901, used a cystoscope to visualize the maxillary sinus through an oroantral fistula, while some years later, in 1922, Spielberg accessed the maxillary sinus using an athroscope via the inferior meatus. However, true advancement in the design of the scopes is what led to the revolution that lay ahead.

Born in 1918 in Leicester, England, Harold Hopkins fell into a career in lens making following graduation, due to the limited number of jobs in his hometown. Eventually, he shifted his focus toward fiberoptics, and 1960 he patented the rod-lens system. Finding no takers for his work in Britain or in the United States, he presented his invention at an exhibition in Germany. Through a friend who was present at the exhibition, Karl Storz came to know about the technology and soon after, the Storz-Hopkins endoscopes became reality.

Storz astounded the medical community with additional technology, the flexible fiberglass gastroscope, presented by the American gastroenterologist Hirschowitz. Combining these technologies, Storz quickly licensed the concept of a fiberoptic light transmission coupled with the rod-lens system. The advent of this technology made way for the fathers of modern day sinus surgery to implement these new tools in the field of otolaryngology.

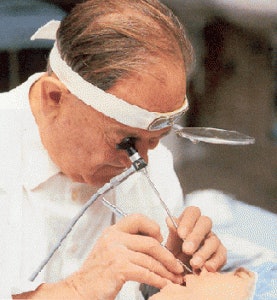

Walter Messerklinger, MD

Walter Messerklinger, MDIn the 1970s, Messerklinger used these endoscopes to visualize the mucociliary clearance patterns that ultimately changed the way sinus surgery was viewed, with the natural ostia of the sinuses found to play the most important role in maintaining the health of the sinuses. Because of this discovery, the need for external approaches to the sinuses became nearly obsolete, as the endoscopes became a mainstay of surgery.

Another Austrian otolaryngologist, Stammberger, was able to translate these observations and descriptions into English and bring them to the United States via Kennedy at Johns Hopkins. By partnering further with Storz, these exceptional surgeons turned endoscopic sinus surgery into what it is today: an art form.