From the Diversity Committee: LGBTIQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Questioning) HEALTH EQUITY

Phyllis B. Bouvier, MD Editor’s Note: Dr. Bouvier has just received the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Award for Humanism in Medicine during our annual meeting. She is also a committee member of both our Diversity Committee and that of the National Medical Assocication. She is Co-Director of Diversity for Kaiser Permanente, CO, and author of Kaiser Permanente’s, “Handbook on Culturally Competent Care. Our increasingly diverse healthcare consumer market is demanding concrete evidence of our ability to provide high quality, cost-effective care. This can only be possible by delivering culturally competent care, care that depends on our ability to acknowledge and understand cultural diversity in the clinical setting, demonstrate respect of the patient’s health beliefs and practices, and which values cross-cultural communication and collaboration. Health equity is the attainment of the highest level of health for all people, and when inequities exist, they result in health disparities for individuals, communities, and global societies. In the U.S., about 9 million people (3.5 percent) identify as “lesbian, gay, or bisexual” (LGB), but about 19 million in the U.S. (8.2 percent) have acknowledged engaging in same-sex sexual behavior. About .3 percent identify as “transgender,” that is, a person whose gender identity (the sense of whether you are male or female) may not be the same as one’s physical birth sex. “Transsexual” is a subset of transgendered. This population has so much gender dysphoria that hormone therapy or surgery is used to make the body genitally congruent with the gender identity. “Intersex” describes the condition in which one is born with external genitalia and/or internal reproductive or sexual anatomy that may not fit the typical definitions of male or female. The number of intersex individuals is estimated to be one in 2,000 newborns each year in the U.S. “Q” refers to someone who is questioning what his or her sexual orientation or gender identity is. The term “queer” may be used by many LGBT youth in the U.S. as a prideful and empowering term, but may have negative connotations depending on the social environment. Sexual behavior may be fluid throughout life, and self-identity may be as well. Sexual orientation (our emotional and physical attraction to others of a particular sex) is only a part of someone’s identity. The LGBTI population is made up of individual heterogeneous groups that include all races, ethnicities, age, socioeconomic status, education, disability or veteran statuses, etc., with distinct health risks, experiences, and care needs. Major barriers to the provision of culturally competent care for the LGBTI patient are: A patient’s sexual identity may be invisible to the physician. Patients are often unwilling to self-identify because of fear of discrimination through historically negative interactions with healthcare institutions and providers. Until recently in parts of the U.S., certain aspects of an individual’s sexuality were illegal. Before 1973 homosexuality was listed as an illness or pathological condition by the American Psychiatric Association. There is often a delay in seeking healthcare. Issues of confidentiality are especially important in the healthcare setting since unintentional “outing” can have significant consequences on social and work status. An additional dilemma for providers involves patients who are minors, since parents would ordinarily be able to review the medical record. A physician’s biases, either implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious), may affect the quality of the interaction. This includes: homophobia (fear of same-gender sexuality); transphobia (fear/hatred of transgendered individuals); and heterosexism (the belief that heterosexuality is the only form of sexuality). Both heterosexual and the homosexual communities often shun bisexuals. Bisexuality is frequently seen as a nonentity—a transitional phase from heterosexuality to homosexuality or vice-versa and/or as denial that one is actually homosexual. Social stigmatization is still prevalent. In the clinical setting, avoid the use of the term “straight” to identify heterosexuals, as it may imply to the LGBTI patient that anything other than straight is “twisted.” There is limited epidemiological research and lack of provider knowledge of specific LGBTI healthcare issues. Invisibility makes it difficult to accrue demographic data that can help identify needs and expectations of this population. What little is known indicates severe disparities for this population. Alcoholism/binge drinking is prevalent and persists with age. Added stresses of being without full legal protection and lack of societal supports for relationships often leads to increased depression and suicide risk. Lesbians have predicted increased risks of breast and ovarian cancer. Transgendered patients may be at increased risk for HIV/AIDS, but remember that sexual behavior and not sexual orientation causes the disease. Transexuals in transition may be more complicated to provide care for with the onset of the Electronic Medical Record. Some transgendered may be living as the opposite sex for one year before surgery has been completed, and they will still require the preventive care of their birth sex. For example, a female transitioning to a male (FTM) still requires a pap test; a MTF will still need a prostate exam. Not surprisingly, the lab thinks there is an error with the test ordered. Intimate partner violence exists. Batterers can be misidentified as victims and treated as such by police and healthcare providers. We must strive to make healthcare an inclusive and safe environment for all. 2014 Committee Applications Opens November 1 Want to get more involved with your Academy? Apply to become a committee member! The 2014 applications will open November 1. You can join an education committee to become more involved in the Academy’s education activities, a BOG committee to become more involved in the grassroots arm of the Academy, or one of the Academy or Foundation committees that fits your area of expertise. Learn more at www.entnet.org/community/committees.cfm.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Bouvier has just received the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Award for Humanism in Medicine during our annual meeting. She is also a committee member of both our Diversity Committee and that of the National Medical Assocication. She is Co-Director of Diversity for Kaiser Permanente, CO, and author of Kaiser Permanente’s, “Handbook on Culturally Competent Care.

Our increasingly diverse healthcare consumer market is demanding concrete evidence of our ability to provide high quality, cost-effective care. This can only be possible by delivering culturally competent care, care that depends on our ability to acknowledge and understand cultural diversity in the clinical setting, demonstrate respect of the patient’s health beliefs and practices, and which values cross-cultural communication and collaboration. Health equity is the attainment of the highest level of health for all people, and when inequities exist, they result in health disparities for individuals, communities, and global societies.

In the U.S., about 9 million people (3.5 percent) identify as “lesbian, gay, or bisexual” (LGB), but about 19 million in the U.S. (8.2 percent) have acknowledged engaging in same-sex sexual behavior. About .3 percent identify as “transgender,” that is, a person whose gender identity (the sense of whether you are male or female) may not be the same as one’s physical birth sex. “Transsexual” is a subset of transgendered. This population has so much gender dysphoria that hormone therapy or surgery is used to make the body genitally congruent with the gender identity. “Intersex” describes the condition in which one is born with external genitalia and/or internal reproductive or sexual anatomy that may not fit the typical definitions of male or female. The number of intersex individuals is estimated to be one in 2,000 newborns each year in the U.S. “Q” refers to someone who is questioning what his or her sexual orientation or gender identity is. The term “queer” may be used by many LGBT youth in the U.S. as a prideful and empowering term, but may have negative connotations depending on the social environment. Sexual behavior may be fluid throughout life, and self-identity may be as well.

Sexual orientation (our emotional and physical attraction to others of a particular sex) is only a part of someone’s identity. The LGBTI population is made up of individual heterogeneous groups that include all races, ethnicities, age, socioeconomic status, education, disability or veteran statuses, etc., with distinct health risks, experiences, and care needs.

Major barriers to the provision of culturally competent care for the LGBTI patient are:

- A patient’s sexual identity may be invisible to the physician. Patients are often unwilling to self-identify because of fear of discrimination through historically negative interactions with healthcare institutions and providers. Until recently in parts of the U.S., certain aspects of an individual’s sexuality were illegal. Before 1973 homosexuality was listed as an illness or pathological condition by the American Psychiatric Association.

- There is often a delay in seeking healthcare. Issues of confidentiality are especially important in the healthcare setting since unintentional “outing” can have significant consequences on social and work status. An additional dilemma for providers involves patients who are minors, since parents would ordinarily be able to review the medical record.

- A physician’s biases, either implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious), may affect the quality of the interaction. This includes: homophobia (fear of same-gender sexuality); transphobia (fear/hatred of transgendered individuals); and heterosexism (the belief that heterosexuality is the only form of sexuality). Both heterosexual and the homosexual communities often shun bisexuals. Bisexuality is frequently seen as a nonentity—a transitional phase from heterosexuality to homosexuality or vice-versa and/or as denial that one is actually homosexual. Social stigmatization is still prevalent. In the clinical setting, avoid the use of the term “straight” to identify heterosexuals, as it may imply to the LGBTI patient that anything other than straight is “twisted.”

- There is limited epidemiological research and lack of provider knowledge of specific LGBTI healthcare issues. Invisibility makes it difficult to accrue demographic data that can help identify needs and expectations of this population. What little is known indicates severe disparities for this population. Alcoholism/binge drinking is prevalent and persists with age. Added stresses of being without full legal protection and lack of societal supports for relationships often leads to increased depression and suicide risk. Lesbians have predicted increased risks of breast and ovarian cancer. Transgendered patients may be at increased risk for HIV/AIDS, but remember that sexual behavior and not sexual orientation causes the disease.

- Transexuals in transition may be more complicated to provide care for with the onset of the Electronic Medical Record. Some transgendered may be living as the opposite sex for one year before surgery has been completed, and they will still require the preventive care of their birth sex. For example, a female transitioning to a male (FTM) still requires a pap test; a MTF will still need a prostate exam. Not surprisingly, the lab thinks there is an error with the test ordered.

- Intimate partner violence exists. Batterers can be misidentified as victims and treated as such by police and healthcare providers.

We must strive to make healthcare an inclusive and safe environment for all.

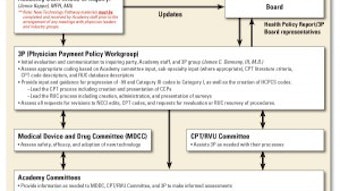

2014 Committee Applications Opens November 1

Apply to become a committee member! The 2014 applications will open November 1. You can join an education committee to become more involved in the Academy’s education activities, a BOG committee to become more involved in the grassroots arm of the Academy, or one of the Academy or Foundation committees that fits your area of expertise.

Learn more at www.entnet.org/community/committees.cfm.