Migraine in Otolaryngology

Clinics are rich with patients whose chief complaints can be attributed to migraine. Understanding migraine pathophysiology offers the practitioner practical options for treatment.

David J. Lafferty, DO, and Michael T. Teixido, MD

According to the World Health Organization, 50% of migraine patients are self-treated and only 10% are seen by a neurologist.2 Most neurologists, however, cannot differentiate between primary vestibular disease and vestibular migraine, rhinosinusitis and sinus headache, or primary and migrainous otalgia. As a result, these and other patients fall in a void that exists between otolaryngology and neurology and go without proper diagnosis or treatment. Fortunately, standard treatments for migraine are successful for the majority of patients with typical and atypical migraine symptoms.

Pathophysiology

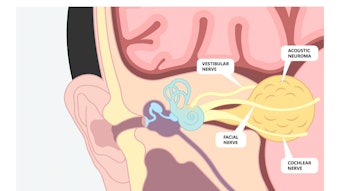

Migraine is best described as a syndrome of hyperactivity of the trigeminal nerve that results in headache accompanied by a wide range of other symptoms. Otolaryngic symptoms can derive from migraine mechanisms in many ways, but perhaps most important is the release of inflammatory neuropeptides from trigeminal fibers on blood vessels. This sensitizes them to pulsation and can lead to mild or severe pain that may accurately be described as a chemical meningitis. These symptoms may occur in any region with trigeminal innervation, most notably intracranial sites, the sinuses, and even the inner ear. Vascular changes including vasoconstriction and dilation are secondary effects of neuropeptide release. Other important changes occur in brainstem nuclei and result in hypersensitivity to and distortions in sensory input. The result is best described as a “sensitive brain” with fluctuating sensitivity to light, sound, motion, smell, and touch.

Waves of spreading depression on the cortex also distort sensory processing and are the origin of aura symptoms. Although visual aura is most common, any area of the cortex may be involved. Vitally important to the otolaryngologist is the increase in parasympathetic activity that accompanies most migraine episodes and leads to congestion, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, and facial swelling that can be misinterpreted as rhinosinusitis or allergy. Atypical symptoms of migraine may be described as non-headache symptoms, which are generated by migraine mechanisms and behave like migraine with response to typical physiologic, environmental, and dietary triggers. These atypical presentations of migraine are common in otolaryngology practice and also respond to typical migraine treatments.

Migraine and Sinus Headache

Patients often present to otolaryngologists with complaints of sinus pressure and sinus headache. Having been inundated with colorful graphics and advertisements for cold medications of bright red throbbing sinuses, it is no wonder that patients often believe that their sinuses are to blame for this discomfort. The 2007 Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS) evaluated 100 patients with self-diagnosed sinus headache and identified only three patients with rhinosinusitis. The remainder of the patients were suffering from some sort of migraine or neuropathic pain. Weather change was reported as a trigger by 83% of these patients.3 The migraine pain experienced may be frontal if V1 is the affected nerve or maxillary if V2 is involved. Rarely the pain may affect the V3 distribution. When patients present to us with facial pain and pressure and rhinosinusitis is ruled out, migraine management is started. Migraine management should be considered in all patients with minimal mucosal disease and persistent symptoms before or after sinus surgery.

Migraine and Vertigo

Vestibular migraine is the most common cause of dizziness. When a patient presents to us with vertigo or dizziness as chief complaint, a careful history as well as a vestibular exam and audiogram can usually make clear whether migraine may be involved. When asked, patients with migraine headache report lightheadedness, motion sensitivity, rocking, swaying, nausea, and displacement in space even when presenting with other primary complaints such as sinus headache.1 Some of these symptoms cannot be produced in the inner ear. When there is no primary labyrinthine disease such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), neuronitis, or Ménière’s disease and headache is present, vestibular migraine is likely. Usually there is a concurrent increase in headache activity with the onset of dizziness. The headache may be mild, never occur at the same time as the dizziness, and in many cases may be absent. Patients often report symptom exacerbation with common migraine triggers such as stress, fatigue, dietary factors, recent illness, weather change, and allergy.

Patients with both vestibular migraine and Ménière’s disease can present with episodes of vertigo with ear pressure and tinnitus. The factor that differentiates the Ménière’s disease is the presence of fluctuating, low-frequency hearing loss. Whereas 13% of the general population have migraine headache, 56% of patients with Ménière’s disease also suffer from migraine. Over 45% of Ménière’s attacks occur with components of migraine such as headache or photophobia.4 This suggests that Ménière’s disease in some individuals may be a complication of migraine. There is a bidirectional association of migraine and Ménière’s that indicates targeting one may help treat the other.5 Some consider the cochlear-vestibular symptoms otherwise consistent with Ménière’s disease to be actually a manifestation of cochlear-vestibular migraine. One study found that 92% of patients with definite Ménière’s to have substantial improvement with a migraine treatment regimen.6

There is also an association between migraine and BPPV. Migraine sufferers are 7.5 times more likely to get BPPV,7 and migraine is 3 times more frequent in idiopathic BPPV than in BPPV secondary to head trauma or surgery.8 One-third of episodes of BPPV start at the time of a headache, and, like migraine, BPPV is more common in women.9 As with Ménière’s disease, BPPV may be a complication of the effects of migraine in the labyrinth. These intra-labyrinthine effects of migraine have been aptly referred to as cochleovestibular migraine.

Migraine and Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss

There is growing evidence to support the relationship between migraine and sudden hearing loss.10 Patients who suffer from migraine are nearly twice as likely to develop a sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL).11,12 When patients present to us with a SSNHL, we treat them with the standard regimen of oral and transtympanic steroid, but we also ask them about their history of migraine. We often find that their hearing loss started during a migraine episode or that they have recently been having uncontrolled migraine headache. In these patients, we will also begin migraine management. Patients who were treated with migraine management in addition to the standard steroid regimen had statistically significant improvements in their hearing at six months compared with those undergoing the standard treatment regimen.13

Migraine and Otalgia

Patients often present with ear pain that after a significant workup for common causes such as otitis media, otitis externa, eustachian tube dysfunction, temporomandibular joint, and referred pharyngeal pain, we are left with no obvious source for the pain. We find that these patients frequently respond to migraine management. In patients presenting to otolaryngologists who screen positive for migraine, 62% reported aural pressure as a symptom,1 and up to 40% of migraine sufferers report ear pain that may last hours to days. In a review of 48 patients from our office for whom no organic cause of otalgia could be determined, 92% responded to standard migraine management.14

Migraine and Tinnitus

There is a link between tinnitus and migraine that can help us to identify patients we may be able to help. About 44.6% of patients who suffer from tinnitus also suffer from migraine. Of those patients about 43% of them report that when they get a headache their tinnitus worsens.15 Two percent of patients with migraine will report pulsatile tinnitus. In one study, 11 of 16 migraine patients reported improvement in their pulsatile tinnitus with migraine management.16 We will often meet patients who have tinnitus that bothers them because it fluctuates in character and intensity. These changes reflect changes in central nervous system arousal. We counsel patients that by treating their migraine, changes of their tinnitus can be stopped making the tinnitus much less bothersome. We also treat patients with fluctuating tinnitus when headache is absent if there is no obvious hydrops.

Treatment Approach

Patient Buy-in and Triggers: It is difficult for patients to accept migraine treatment if their symptoms are different than the migraine they know about. This requires education about migraine pathophysiology and triggers and reassurance that they are aware of only one common form of migraine, migraine headache. The mainstays of treatment for migraine headache and atypical migraine symptoms are lifestyle change and trigger identification and avoidance. Unlike many environmental and physiologic triggers, dietary triggers can be avoided. There are many migraine diets available, but we discourage our patients from adhering too strictly to them as the diet itself may become a source of stress and be counterproductive. In general, an attempt to improve lifestyle by reducing strong dietary triggers (alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, aged cheese), stress, dehydration, and fatigue and adding regular exercise are beneficial. When done maximally, many patients will obtain near complete freedom from their migraine symptoms with this treatment alone.

When symptoms are persistent, preventive medications are given to elevate the threshold above which migraine triggering in the brain occurs. This is often necessary in patients with chronic migraine as seen in the otolaryngology clinic population. These may be medications originally used for blood pressure control (calcium channel blockers, e.g., diltiazem, verapamil, and beta blockers, e.g., propranolol), depression (TCAs, e.g., nortriptyline; SNRIs, e.g., venlafaxine; and SSRIs, e.g., paroxetine), or seizures (sodium channel blockers, e.g., topiramate, valproate, gabapentin) that have been found to be easily tolerated and very good at preventing frequent migraine symptoms. These medications act in different ways to reduce neural sensitivity in the central nervous system. When preventive medications are successful, breakthrough attacks that do occur are often easily attributed to some particular trigger or aggravating factor, which can then be avoided. We reassure our patients that because of the plasticity of the nervous system, treatment is not lifelong and can often be discontinued after a period of good symptom control.

Allergy is an aggravating factor for migraine, and there is a direct correlation between degree of atopy and frequency and intensity of migraine episodes. The onset or pattern of symptoms in our patients is sometimes seasonal and associated with a rise in atopy. We screen our patients for symptoms of allergy and recommend antihistamines or allergy testing if present. Immunotherapy is associated with a decrease in the frequency and intensity of migraine headache.17

Summary

In otolaryngology practice, our clinics are rich with patients whose chief complaints can be attributed either partially or fully to migraine. An understanding of migraine pathophysiology and its contribution to these complaints offers the practitioner practical options for treatment of these patients. Comfort prescribing the four main classes of preventive medications comes quickly and is very rewarding in the clinic. Good patient and physician resources are also available from the Migraine in Otolaryngology Society.

References

- Schulz KA, Esmati E, Teixido M, Godley FA, et al. Patterns of migraine disease in otolaryngology: a CHEER network study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(1):42-50. doi:10.1177/0194599818764387

- World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44571

- Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS): CME. Headache. 2007;47(2):213-224. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00688.x

- Radtke A, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H. Migraine and Ménière’s disease: is there a link? Neurology. 2002 Dec 10;59(11):1700-1704. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036903.22461.39

- Kim SY, Lee CH, Yoo DM, et al. Association between Meniere disease and migraine. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(5):457-464. doi:10.1001/JAMAOTO.2022.0331

- Ghavami Y, Haidar YM, Moshtaghi O, Lin HW, Djalilian HR. Evaluating quality of life in patients with Meniere's disease treated as migraine. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018 Dec;127(12):877-887. doi: 10.1177/0003489418799107

- von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lexius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:710-715.

- Ishiyama A, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Migraine and benign positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109(4):377–380.

- Ogun OA, Janky KL, Cohn ES, Büki B, Lundberg YW. Gender-based comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 4;9(9).

- Hamed SA, Youssef AH, Elattar AM. Assessment of cochlear and auditory pathways in patients with migraine. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33(4):385-394. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.10.008

- Mohammadi M, Taziki Balajelini MH, Rajabi A. Migraine and risk of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1089-1095. doi:10.1002/lio2.477

- Chu CH, Liu CJ, Fuh JL, Shiao AS, Chen TJ, Wang SJ. Migraine is a risk factor for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a nationwide population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(2):80-86. doi:10.1177/0333102412468671

- Abouzari M, Goshtasbi K, Chua JT, et al. Adjuvant migraine medications in the treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(1):E283-E288. doi:10.1002/lary.28618

- Teixido M, Seymour P, Kung B, Lazar S, Sabra O. Otalgia associated with migraine. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(2):322-325. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318200a0c4

- Langguth B, Hund V, Busch V, et al. Tinnitus and headache. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:797416. doi:10.1155/2015/797416

- Weinreich HM, Carey JP. Prevalence of pulsatile tinnitus among patients with migraine. Otol Neurotol. 2016 Mar;37(3):244-247. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000968

- Martin VT, Taylor F, Gebhardt B, et al. Allergy and immunotherapy: are they related to migraine headache? Headache. 2011;51(1):8-20. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01792.x