The State of the Workforce: Our Supply System

Gain valuable insights from the recent Otolaryngology Workforce Report, including evolving trends, access disparities, and strategies to address future challenges.

Andrew J. Tompkins, MD, MBA, Chair of the AAO-HNS Workforce Task Force

The purpose of our graduate medical education (GME) system is to act as the supply mechanism for our workforce. An efficient supply system will respond to demand dynamically. Demand is most importantly defined by access, which can be further defined by wait time, distance, and skill set delivery. So, as with our workforce, we must analyze whether our GME supply system is dynamic and creates access on these fronts, given the demands. In this issue, we will examine our supply system, whether that system is achieving these goals, and how to better optimize it for success.

New supply for our workforce is, for the most part, dependent on 131 ACGME-accredited training programs across the U.S.1 Since 2017, we have seen a substantial growth in programs and, more recently, in graduates per year. The number of programs has grown by 13 since 2017, representing an 11% growth.1 The graduates per year have grown from 333 in 2021 to an expected graduate number of 386 in 2028, representing a 16% growth.2 The adequacy of this recent growth, as well as our entire GME system, can’t be assessed by these simple numbers but rather should be examined through the lens of patient access.

Several factors cut in different directions as to whether this growth is optimal. We saw a very high rate of planned retirement in our 2022 survey, with 9.5% of actively practicing otolaryngologists having plans to retire within two years.3 This exodus is not sustainable, but it represents a substantial segment of our workforce that might have retired by now, necessitating more labor. Also, more graduates are gravitating towards academic practices, 4 which have the least clinical days per week5 and lowest patient visits per day.6 These productivity differences would seem to necessitate more graduates. On the flip side, we see robust use of advanced practice providers (APPs) in almost all settings,7 most of whom see patients independently.8 Where these and many other factors ultimately play out from an access perspective is with wait times, which we need to track in a more nuanced manner to truly understand these effects. Recent wait time data suggest we are struggling to meet demand in some environments,9 which will guide researchers as we study access moving forward.

Figure 6.1. APP Use by Practice Type

Figure 6.1. APP Use by Practice Type

Reproduced from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce (Figure 6.1, pp 59)

Concentration in Urban Environments

From a distance perspective, our current supply system appears to struggle with access. Increasingly, our graduates have pursued fellowships and academic careers. While this trend has the benefit of more competence on a tertiary basis, what this means from a geographic perspective is that we are increasingly concentrated in urban environments. Academic office locations are overwhelmingly urban,10 as is fellowship concentration.11 The net result is that physicians in rural office locations are voicing an increased need for more physicians in these areas. As indicated by supply perception both by practice type and rurality, we seem to have more of a geographic dispersion problem than an overall numbers problem.

Table 5.4. Urban/Rural Distribution by Practice Type by Total Office Locations Reproduced from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce (Table 5.4, pp 56)

Another notable fact regarding graduate growth is that despite the recent growth of new programs, most of the recent graduate growth per year is from older programs, by a 2-to-1 margin.12

Figure 1.2. New versus Established Program Graduate Increases per Year

Figure 1.2. New versus Established Program Graduate Increases per Year

Reproduced from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce (Figure 1.2, pp 20)

The outsized growth in established programs seems to be disconnected from commonly described incentives for resident training growth, namely Medicare GME payments and increasing the FTE cap. Because Medicare funding is the typical go-to solution for GME payments and incentives, it is worth exploring these payments in a bit more detail.

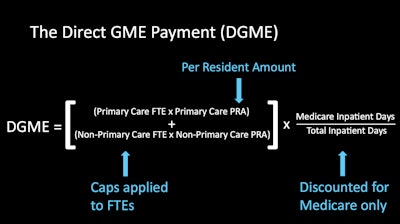

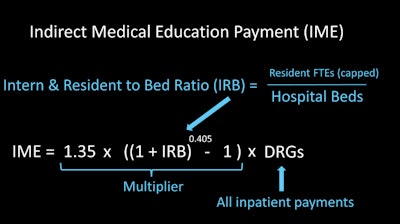

Medicare funds GME programs through two main payment mechanisms: a direct GME (DGME) payment and an indirect medical education (IME) payment.13 The formulas for each are shown below. The per-resident amounts (PRAs) were established through hospital cost reports from 40 years ago and are indexed to inflation. Resident FTE funding caps were created in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which has the effect of constraining payments when growing residencies. The traditional argument is that to grow residency slots we need to increase the cap allowed.

The curious aspect about the growth in established programs, the majority of which operate under the resident cap mandate, is that they do not obtain more money from Medicare by adding more residents. In fact, the funding formula acts as a financial disincentive when adding a new resident when at or above the cap, which 70% of hospitals were in 2018.13 Those training programs over the cap tended to look like our established training programs—large hospitals with a large GME contingent (>135 residents).13 And yet those programs are the main generators of resident growth. Also, if new otolaryngology programs were at institutions that already had any established GME program, they too would be held to an institutional cap that was set five years after those other programs started.13 Something else significant is providing a growth incentive for all these programs. These reasons are worth exploring further, but this growth should also make us question whether our supply system incentives are appropriately structured to provide patient access.

The Payer System Needs a Revamp

Under the current system, the funding formula does not act as an optimal incentive system. The yearly PRA and inpatient payment inflationary bumps crudely increase yearly payments, but these are disconnected from training capacity needs. More importantly, the formula does not act as a means of signaling demand, discerning which specialties are in higher demand, and incentivizing the supply system to meet that demand from a time and distance perspective. On principle, if all areas of society are paying into Medicare (and Medicaid, which also helps to fund most GME programs), shouldn’t we strive for an incentive system that motivates our supply system to meet societal demand in a nuanced manner? Simply increasing the cap is not an ideal lever since it does not necessarily mean that money will be available for otolaryngology, nor is the hospital necessarily required to even spend these payments on GME. The payment system needs a revamp that is specialty-specific and nuanced to specialty demand needs.

One potential solution that programs can employ more immediately, while using a GME funding carve-out to potentially motivate growth and address the previously described distance access issue, is creation of rural track programs.14 Currently, we have no such programs despite the societal need for care in these areas. Most of the key indicator cases and surgical need are not necessarily tertiary in nature, which makes considering rural path programs and partnerships even more feasible. Societal demand and funding are in place to make this happen. Such program creation will take time and leadership, and the effects of such programs need to be studied longitudinally to see where graduates practice. But we have an opportunity to expand our training outward rather than vertically to serve demand needs.

Perhaps overlapping with the above partnership opportunity, residents expressed an overwhelming desire to have more exposure to the business of medicine15 and private practice.16 Couldn’t rural GME expansion with the help of private practice and nonacademic hospitals serve all interests? We have an opportunity to reshape GME in a manner that serves both resident education and societal demand while uniting us more as a specialty. Academic and private practice partnerships can both increase worker supply and provide for resident exposure to private practice, which were consistently cited as the top four ways private practices can improve recruitment.17 Leadership on this front is not bound by academic status, though a significant push will need to come from that community. All practice environments must be willing to contribute to resident training to find a more optimal solution.

![Figure 4.7. Top 10 Methods to Improve Recruitment by Practice Environment [Private Practice Environments] Reproduced from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce (Partial reproduction of Figure 4.7, pp 49)](https://img.ascendmedia.com/files/base/ascend/hh/image/2025/03/Bulletin_Methods_to_Improve_Recruitment.67d88a0714044.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) Figure 4.7. Top 10 Methods to Improve Recruitment by Practice Environment [Private Practice Environments]

Figure 4.7. Top 10 Methods to Improve Recruitment by Practice Environment [Private Practice Environments]

Reproduced from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce (Partial reproduction of Figure 4.7, pp 49)

Our training programs are wonderful, perhaps the crown jewel of our specialty. But, as with anything from a quality improvement perspective, we must keep being introspective to make resident education even better—to advocate for better incentive structures, optimize our training and partnerships, and serve our patients in the best way possible.

References

- Page 10, “Graduate Medical Education Training,” from The 2022 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2023.

- Figure 1.1, “Graduating Residents per Year,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Page 92, “Otolaryngologists with Active Plans to Retire,” from The 2022 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2023.

- Page 30, “Relative Practice Setting Dispersion for Largest Practice Settings by Decade,” from The 2022 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2023.

- Table 7.2, “Clinical Days Worked Per Week by Practice Type,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Figure 7.4, “Patients Seen Independently of APP/Resident/Fellow during Full Workday,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Figure 6.1, “APP Use by Practice Type,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Figure 6.5, “How APPs See Patients by Practice Type,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Corbisiero MF, Muffly TM, Gottman DW, et al. Insurance Status and Access to Otolaryngology Care: National Mystery Caller Study in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024; 171(1): 98-108.

- Table 5.4, “Urban/Rural Distribution by Practice Type by Total Office Location,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Page 34, “Urban vs Rural Practice Divide by Fellowship Training,” from The 2022 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2023.

- Figure 1.2, “New versus Established Program Graduate Increases per Year,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Physician Workforce: Caps on Medicare-Funded Graduate Medical Education at Teaching Hospitals. GAO-21-391. Washington D.C.: GAO, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-391.pdf.

- “Rural Track Program Designation,” Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, accessed February 2, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/initiatives/medically-underserved-areas-and-populations/rural-tracks/.

- Table 1.3, “Do You Desire More Exposure to the Business of Medicine,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Figure 1.8, “Desire for More Exposure to Private Practice by Current Exposure,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Figure 4.7, “Top 10 Methods to Improve Recruitment by Practice Environment,” from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.