Surgical Management of Esophageal Disease

Multidisciplinary discussions can help inform the best treatment approach and achieve the best patient outcome.

Douglas C. von Allmen, MD, and Micheal J. Rutter, MD

The following article provides highlights from the authors’ Expert Lecture, “The Surgical Management of Esophageal Disease: The Role of the Otolaryngologist,” presented at the AAO-HNSF 2024 Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO.

The role of the otolaryngologist in the management of esophageal disease is inherent to the interplay of the trachea and esophagus as symbiotic structures that together make up part of the aerodigestive system. The overlap of disciplines that manage esophageal disease, including general surgery, gastroenterology, and otolaryngology, encourages clinicians to participate in multidisciplinary discussions to determine the best treatment approach to achieve the best patient outcome. Tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEF), esophageal atresia, laryngeal cleft, button battery injury, and caustic ingestion are some examples of esophageal pathology that benefit from multidisciplinary evaluation, where the otolaryngologist plays an important surgical role.

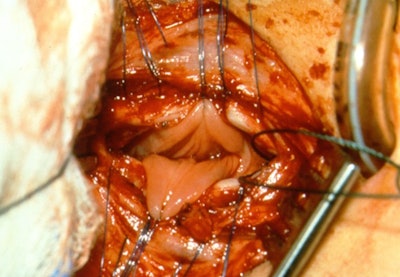

A TEF may be congenital or acquired. Most commonly, congenital TEF is associated with esophageal atresia (EA). The location and size of a fistula can help determine the best approach. Fistulas in the distal third of the trachea are usually best served by general surgery. Fistulas in the proximal third of the airway are often best addressed by otolaryngology and the middle third may be addressed by either discipline. H-type tracheoesophageal fistulas in the proximal third of the airway can be approached with a trans-tracheal approach to avoid lateral dissection and risk to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. This technique allows for multi-layer closure by working through a tracheotomy and separating the trachealis and esophagus around the periphery of the defect. The esophageal layer is then closed (Figure 1) followed by the placement of an interposition fascia graft and finally closure of the trachealis and tracheotomy.

Figure 1. Exposure of esophageal mucosa through an anterior tracheotomy overlying the TEF.

Figure 1. Exposure of esophageal mucosa through an anterior tracheotomy overlying the TEF.

Acquired fistulas can occur related to iatrogenic injury from tracheostomy tube placement or intubation injury. They can also occur as a result of caustic ingestion or button battery ingestion. When the defect is large, but the esophagus is otherwise patent above and below the fistula, a modified slide tracheal resection technique can be used to effectively repair both the esophagus and trachea. In this technique, the trachea is transected in a beveled fashion above and below the proximal and distal aspect of the defect respectively. The tracheal wall overlying the defect is then trimmed and left pedicled to the lateral aspect of the fistula and flipped down in a trap door fashion to close the esophageal defect (Figure 2). An interposition graft is then placed, and the tracheal anastomosis is performed.

Figure 2. EGD following repair of TEF using pedicled tracheal wall and slide tracheoplasty.

Figure 2. EGD following repair of TEF using pedicled tracheal wall and slide tracheoplasty.

Type 3 clefts can be repaired similarly as an H-type TEF through an open tracheotomy with the tracheal and esophageal layers being separated up through the larynx. The esophageal layer is closed followed by the tracheal layer. Interposition grafting can be considered in this instance as well and should be considered especially in the instance of revision surgery and in patients with a history of Opitz syndrome. Long type 4 clefts are better approached with a tracheal transection technique. In this technique, a transverse tracheotomy is made just below the cricoid and the trachea is peeled anteriorly off the esophagus. Care should be taken to make sure that enough tissue is present to close the trachea as esophageal replacement can be considered in the future if sacrifice of the esophageal tissue is needed. The esophagus is then closed. Interposition grafting should be used to cover the distal aspect of the closure primarily since proximal breakdown is more easily addressed from a revision standpoint.

Esophageal strictures can occur in patients with esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula (EA/TEF) or as a result of esophageal injury. Management of esophageal strictures primarily starts with conservative methods such as endoscopic dilation and stenting. When these methods are unable to achieve a functional patent lumen, an open approach may need to be considered. Strictureplasty is a technique that can be used for short segments of stenosis where the esophagus is incised longitudinally over the stenotic segment and then closed in the opposite direction to widen the segment of the esophagus.1 Alternatively, resection can be considered for short segments of stenosis. These patients may have had multiple thoracotomies or thoracoscopic procedures in the past. If the esophageal stenosis is also associated with a tracheoesophageal fistula, a trans-tracheal approach to the esophagus via tracheal transection is a technique we have used in this specific circumstance. The benefit of this approach is that it provides an easier pathway to the source of stenosis and allows for the management of the fistula concurrently.

All efforts should be made to maintain the native esophagus; however, for longer segments of stenosis or in cases of congenital long-gap esophageal atresia where the ends cannot be brought together, esophageal replacement is a consideration. Options for esophageal replacement include gastric pull-up, reverse gastric tube, colon interposition, and jejunum interposition.2 All of these options come with morbidity with reflux being the most common postoperative issue. Patients must eat upright since these conduits are not functional for peristalsis. While these replacements are typically performed by our general surgery colleagues, otolaryngologists can be called upon to perform the neck dissection portion of the surgery. We are not only more familiar with neck anatomy but are generally more aware of recurrent laryngeal nerve identification and preservation.

Preoperative assessment of a patient who needs an esophageal replacement includes review of imaging to determine the course of the esophagus and location of the stenosis. It is also helpful to perform an awake flexible laryngoscopy to determine the status of vocal fold motion. Intraoperative recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring should be used, if possible, though there are several challenges to this in younger children. When identifying and isolating the proximal esophagus, placement of an esophageal endotracheal tube or bougie can help with palpation and identification of the esophagus. A traction stitch in the anterior trachea can also aid in the retraction of the trachea away from the esophagus and can be particularly helpful in avoiding injury to the trachealis. Circumferential dissection of the esophagus in one location and placement of a Penrose drain around the esophagus can aid in retraction and facilitate further proximal and distal mobilization.

If enough proximal esophagus is present, esophagostomy is an alternative technique that can be used for long-term diversion of saliva. This is particularly helpful if the patient is too ill to undergo definitive replacement. Esophagostomy is also a tool that can be used for patients with long-gap esophageal atresia who are awaiting replacement. After an esophagostomy is healed it allows the patient to sham feed, which is particularly helpful for infants to facilitate the development of a functional swallow.

Esophagostomy is performed by transecting the esophagus as distally as possible. The distal stump of the esophagus is then oversewn. Marking this with a clip and/or suturing it to the underside of the sternocleidomastoid can aid in identifying the distal remnant during future surgeries. The transected proximal end is then brought out to the skin and sutured circumferentially with interrupted stitches. It can be helpful to bring the esophageal lumen out through a different incision in the skin to avoid the risk of breakdown of the cervical incision made for dissection, however, this may not be possible due to length restrictions. Good postoperative care of the incision is important due to continued salivary flow onto the neck. One option to manage saliva is to place an ostomy bag over the esophagostomy to prevent having to make frequent dressing changes.

Long-term follow-up care of patients undergoing esophageal surgery is critical for the early identification of complications and other associated morbidity. Esophageal dysmotility is a problem inherent to this population. Worsening dysphagia symptoms should prompt further evaluation. Monitoring for malnutrition is also important, especially for young children. For EA/TEF and caustic ingestion patients, long-term screening for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer is prudent.3

Otolaryngologists can play the primary or supporting role in the management of complex aerodigestive lesions involving the esophagus. A comprehensive preoperative evaluation of the patient and multidisciplinary discussion can help determine how we can best serve patients with esophageal pathology.

References

- Anderson KD, Acosta JM, Meyer MS, Sherman NJ. Application of the principles of myotomy and strictureplasty for treatment of esophageal strictures. Journal of Ped Surg. March 2002. 37(3):403-6.

- Reinberg O. Esophageal replacements in children. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Oct 2016. 1381(1):104-112.

- Krishnan U, Dumont MW, Slater H. et al. The International Network on Oesophageal Atresia (INOEA) consensus guidelines on the transition of patients with oesophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula. Nature Reviews Gastro & Hep. 2023 20:735-755.