Pre-Columbian otolaryngology in Mexico

“As president of the AAO-HNS/F, it is my great honor to welcome the Mexican delegation from the Mexican Federation of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (FESORMEX) and the Mexican Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (SMORLCCC) to our Annual Meeting in Chicago.

“As president of the AAO-HNS/F, it is my great honor to welcome the Mexican delegation from the Mexican Federation of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (FESORMEX) and the Mexican Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (SMORLCCC) to our Annual Meeting in Chicago. We look forward to our societies working together for the care of patients worldwide through collaboration and friendship now in Chicago, and into the future.”

— Gregory W. Randolph, MD

AAO-HNS/F President

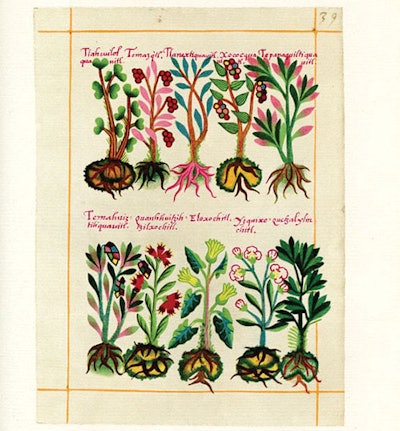

Figure 1. Codix de la Cruz-Badiano

Figure 1. Codix de la Cruz-BadianoJavier Dibildox, MD, professor, service of Otolaryngology on the faculty of Medicine at the Autonomus University of San Luis Potosí, and Hospital Central and I. Morones Prieto, MD, San Luis Potosí, México.

The conquest of Tenochtitlan in 1520 was the beginning of a rapid decline of the pre-Columbian civilizations. The destruction of the native codices, schools, and temples was an enormous historical loss. In an attempt to rectify, the Spanish recruited elderly Indians to produce new codices and to document a wide selection of historical, medical, and cultural subjects. (See Figure 1.)

Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún published the book General History of the Things of New Spain in 1580, in which he describes the diseases of the human body and the medicines against them. This is the first publication that organized the diseases of the head, eyes, ears, teeth, and nose, as well as the diseases and medicines for the neck and throat, in a similar manner as today´s ENT books.

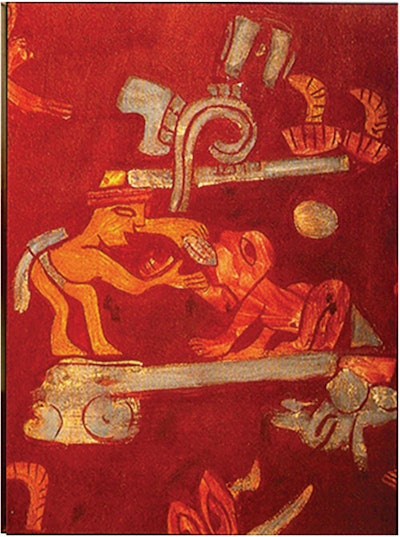

Figure 2. Mural of medical science in

Figure 2. Mural of medical science inTepantintla showing treatment of a

lesion in the mouth.

The education of the Aztecs was important and mandatory. The small children were educated by their parents and girls by mothers. (See Figure 2.) Among the Aztecs, the physicians came from families dedicated to the science of healing, and it was a father’s duty to share his knowledge of medicine with his sons. The knowledge of medicine of the Aztec and Maya was superior to any other civilization of their time. In Texcoco and in Tenochtitlan, to practice medicine, it was necessary to present an examination at the end of the training. After a successful examination, approval was required from one of the four heads of government.

The art of healing was exercised by the Tlamatepa-Titícitl that used ingested or topical medicines and by the Texoxotla-Tícitl that cured with surgery.

Because they believed that diseases were due to the influence of gods, stars, and planets, the doctors were also trained in religion and astronomy and accumulated a great collection of medical information and skills. They divided their practice into several specialties, such as general practice, surgery, orthopedics, dentistry, and otology. Motolinia said, “They have their own native skilled doctors who know how to use many herbs and medicines, which suffices for them. Some of them have so much experience that they were able to heal Spaniards, who had long suffered from chronic and serious diseases.”

The physicians used complex surgical techniques in human sacrifices, cranial trepanations, deformations, femur factures, eye surgery, dental fillings, and in dentistry, the insertion of small round pieces of jade or pyrite. The tonsils (“sequillas”) were extirpated with a knife, followed by the application of ground picete, yietl and salt, then when the flesh rots, a dry agave powder was applied in the lesion. When the fibrinoid exudate appeared in the tonsillar bed, a small amount of sun-dried agave was taken, then sprayed on the bed.

They used fish bones with clean human hair or sharp cactus thorns with fibers of the agave leaf as needles and thread to suture wounds. Cuts and wounds on the nose, lips, and face were treated by suturing with hair and applying interrupted stitches; afterward, the wound was covered with melted juice from the agave cactus or white honey and salt to prevent infections. If an unattractive scar remained, it was removed, the wound burned and sutured again with hair, and covered with liquid rubber. If the nose fell off or if the treatment was a failure, an artificial nose was applied.

References:

- Sahagún Fr. Bernardino de. Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España. 1999 México. ed. Porrúa.

- Motolinía, Friar Toribio de. 1971 [1541] Memoriales o libro de las cosas de la Nueva España y de los naturales de ella, E. O’Gorman, ed. Mexico: UNAM.

- Viesca T V. Medicina Prehispánic de México.Ed. Panorama, México,2002.