From the Education Committees | Acute Laryngeal Injury and COVID-19: The Perfect Storm

Anecdotally, patients with laryngeal, subglottic, or tracheal scar after severe COVID-19 have represented an increasing proportion of patients in tertiary airway centers.

Acute Laryngeal Injury

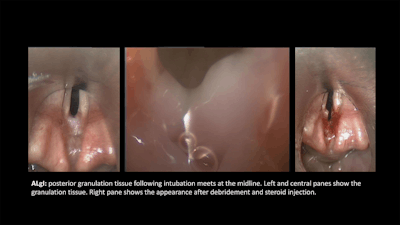

Acute laryngeal injury (ALgI) is ulceration, and/or granulation tissue of the laryngeal mucosa. It is frequently encountered following prolonged intubation when the curvature of the cervical spine and the displacement of the sedated tongue base force the endotracheal tube posteriorly against the laryngeal framework.1 Pressure injury to the laryngeal mucosal injury can lead to fibrotic contracture, which tethers the cricoarytenoid joint complexes and can result in posterior glottic stenosis.2 ALgI has been prospectively observed in 57% of patients after ICU mechanical ventilation and is associated with significantly worse breathing and voicing 10 weeks after extubation.3

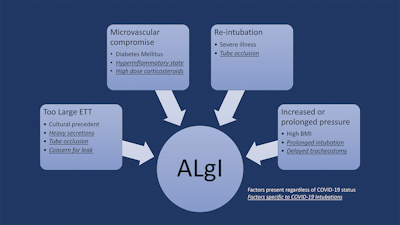

Pre-pandemic research showed that patients with comorbid diabetes mellitus, elevated BMI, and an endotracheal tube larger than 7.0 had an increased incidence of ALgI after prolonged intubation.3 The data suggest that intensivists should consider using ETT sizes less than 7.5 for patients to limit laryngeal injury and highlight the importance of adhering to recommended guidelines on appropriate ETT size based on height. This is the one established risk factor for ALgI that can be directly modified (in partnership with intensivists and emergency physicians) to immediately benefit patients. Further research is needed to confirm if decreasing ETT size beyond current height-based sizing nomograms further reduces the risk of laryngeal injury.

Once ALgI has been identified, early intervention to prevent scaring reduces the number or required operations and the need for open airway reconstruction compared to intervening following the development of mature scar.4 Early intervention in patients with ALgI and tracheostomy reduces the duration of tracheostomy dependence and the number of interventions required to achieve decannulation.3 Intervention to treat ALgI in the acute phase consists of endoscopic removal of granulation tissue and fibrinous debris, injection of corticosteroids. Protocolized approaches to early intervention for ALgI and large prospective studies are needed.

The impact of ALgI on recovery from critical illness coupled with the proven benefit of early intervention to promote laryngeal function after prolonged intubation elevate the importance of post-extubation surveillance of high-risk patients. Individuals with high BMIs or diabetes are particularly vulnerable and benefit from close airway monitoring after extubation.

Laryngotracheal Impact of COVID-19

As with so many research efforts, the work to improve outcomes for patients with ALgI has already been shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic. In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic escalated in the United States and around the world, initial responses from professional societies emphasized the risk of disease transmission sometimes at the cost of departing from existing patterns of care. Many hospitals protocolized delaying tracheostomy for two to four weeks and preferentially selecting large endotracheal tubes to maximize secretion management and minimize ventilatory leak with droplet escape.

Even as expanded clinical experience with COVID-19 improved survival from severe disease, insults to laryngotracheal health continued to accumulate. Molecular evidence of dramatic inflammation in the proximal airway mucosa reinforced the susceptibility of the airway to injury from elevated cuff pressure.5 Corticosteroids became a mainstay therapy for severe cases of the disease.6 This was accompanied by increasing rates of adrenal insufficiency, unmasking of diabetes mellitus, and muscle atrophy.1 Microvascular vulnerability and impaired wound healing also contribute to proximal airway injury after prolonged intubation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, laryngotracheal injury in real-world settings increased.8,9 In one U.S. laryngology practice, 40% of sequentially collected patients seen in clinic after COVID-19 intubation reported unilateral vocal fold paralysis, 15% had posterior glottic stenosis, and 10% had subglottic stenosis.8 In Italy, a large prospective cohort evaluated after mechanical ventilation for COVID-19 showed that 22.5% had fixed obstruction on PFTs consistent with laryngotracheal stenosis.9

ALgI in the Time of COVID

Anecdotally, patients with laryngeal, subglottic, or tracheal scar after severe COVID-19 have represented an increasing proportion of patients in tertiary airway centers. Even this information is likely to dramatically under-represent the problem as patients continue to rehabilitate from their illness with a tracheostomy that masks the underlying anatomic derangement in the proximal airway. Experience to date across multiple centers suggests that laryngotracheal scar will be a fixture of COVID survivorship for a large proportion of patients. Now more than ever, we believe focused approaches to early ALgI detection and treatment after extubation can serve to reduce the rates of laryngotracheal stenosis and promote functional recovery from critical illness. For patients with laryngotracheal stenosis secondary to prolonged intubation for severe COVID-19, expedient diagnosis, early treatment, and rapid referral of recalcitrant patients to tertiary care centers will be increasingly important as we work to restore laryngeal function after prolonged intubation resulting from COVID-19.

![Getty Images 1013668346 [converted] 01](https://img.ascendmedia.com/files/base/ascend/hh/image/2022/03/GettyImages_1013668346__Converted__01.6244bdb1d9995.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=191&q=70&w=340)