Providing Hope and Humanitarianism in Riobamba, Ecuador

Stewart I. Adam, MD, resident, Yale-New Haven Hospital Many physicians go into training and practice with the goal of helping patients and contributing meaningfully to society’s betterment. Perspective on the privileges and accompanying responsibilities of being a physician can sometimes be lost, especially during training, where a large body of specialty-based knowledge and surgical skills are developed in the midst of a busy clinical experience. My travel to Riobamba, Ecuador, November 8-16, 2013, helped reinvigorate a personal sense of humanitarianism as the driver of compassionate, artful care. Our team consisted of 25 healthcare workers, including anesthesiologists, pediatricians, scrub techs, nurses, and two otolaryngologists. Howard Boey, MD, led the group for the ninth year and provided me great mentorship and training. We worked with the private charitable organization FIBUSPAM (http://www.clinicadulcerefugio.com), which was integral in providing a base in Riobamba, organizing patient recruitment, and facilitating the use of the Galapagos Military Hospital for cases requiring general anesthesia. For a few team members, including myself, the mission was our first experience in Ecuador. Riobamba is a small Andes Mountain city in the Chimborazo Province, nestled between active volcanoes, about 125 miles south of Quito, the country’s capital city. The average household income is about $4 a day. Indigenous populations are prevalent and subsistence farming is the dominant economic activity. There is widespread poverty, unemployment, and hopelessness. Basic primary medical care is limited, and the more indigenous and impoverished people have virtually no access to surgical subspecialties such as ENT. After taking a redeye flight to Quito and a five-hour drive through the Andes to Riobamba via military buses, we were greeted with a reception featuring indigenous music and dance at the FIBUSPAM clinic. Medical supplies were largely donated and consisted of surgical instruments/kits, medications, anesthesia equipment, microscope, NIMS machine (charitable donation from Medtronic, Inc.), food, etc. Each team member transported supplies in large hockey bags. The equipment required significant manpower in organizing, assembling, and deploying. Our first workday was spent screening 200-plus patients at the military hospital site. Some patients traveled more than 10 hours from the Amazon basin region of Ecuador. A significant portion of patients had cleft lips, palates, and noses in various pathologies and stages of repair. Some were infants with primary lips, others returned to have their palates repaired following successful lip surgery from the previous mission. A few patients developed palate fistulas following repair, and some teenagers and young adults arrived for cleft nose surgery. Following patient screening, we planned the next four operative day schedules. We completed 61 surgical procedures in four days. Cases included cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, definitive open septo-rhinoplasty for cleft nose, thyroidectomies, tympanoplasties, a few adenotonsillectomies, and two congenital aural atresia repairs. The operative cases provided a great supplement to residency training and experience in managing cleft patients. The most meaningful part of the trip and surgical care was talking with the parents following the cases in our make-shift PACU and seeing the looks of joy, excitement, and hope on their faces. The mission met its goals of creating accessible care to those most in need. A key factor to this successful trip was working through a well-established organization that coordinated appropriate patients for screening. The most disconcerting aspect of the care we provided is not being able to directly follow up with our patients. The FIBUSPAM clinic did arrange follow-up and we have been able to correspond with two local general surgeons and see patient photos. Working in Riobamba was enriching. I plan to participate in future medical mission trips and strongly encourage my peers to do the same. I am grateful to the AAO-HNS humanitarian grant for funding my trip.

Stewart I. Adam, MD, resident, Yale-New Haven Hospital

Stewart Adam, MD, with a patient and mother after cleft palate surgery.

Stewart Adam, MD, with a patient and mother after cleft palate surgery.Many physicians go into training and practice with the goal of helping patients and contributing meaningfully to society’s betterment. Perspective on the privileges and accompanying responsibilities of being a physician can sometimes be lost, especially during training, where a large body of specialty-based knowledge and surgical skills are developed in the midst of a busy clinical experience. My travel to Riobamba, Ecuador, November 8-16, 2013, helped reinvigorate a personal sense of humanitarianism as the driver of compassionate, artful care.

Our team consisted of 25 healthcare workers, including anesthesiologists, pediatricians, scrub techs, nurses, and two otolaryngologists. Howard Boey, MD, led the group for the ninth year and provided me great mentorship and training. We worked with the private charitable organization FIBUSPAM (http://www.clinicadulcerefugio.com), which was integral in providing a base in Riobamba, organizing patient recruitment, and facilitating the use of the Galapagos Military Hospital for cases requiring general anesthesia.

Drs. Adam and Howard Boey with a patient and mother after cleft lip surgery.

Drs. Adam and Howard Boey with a patient and mother after cleft lip surgery.For a few team members, including myself, the mission was our first experience in Ecuador. Riobamba is a small Andes Mountain city in the Chimborazo Province, nestled between active volcanoes, about 125 miles south of Quito, the country’s capital city. The average household income is about $4 a day. Indigenous populations are prevalent and subsistence farming is the dominant economic activity. There is widespread poverty, unemployment, and hopelessness. Basic primary medical care is limited, and the more indigenous and impoverished people have virtually no access to surgical subspecialties such as ENT.

After taking a redeye flight to Quito and a five-hour drive through the Andes to Riobamba via military buses, we were greeted with a reception featuring indigenous music and dance at the FIBUSPAM clinic. Medical supplies were largely donated and consisted of surgical instruments/kits, medications, anesthesia equipment, microscope, NIMS machine (charitable donation from Medtronic, Inc.), food, etc. Each team member transported supplies in large hockey bags. The equipment required significant manpower in organizing, assembling, and deploying.

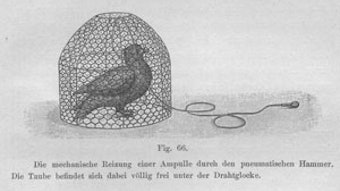

Patients lined up for screening day.

Patients lined up for screening day.Our first workday was spent screening 200-plus patients at the military hospital site. Some patients traveled more than 10 hours from the Amazon basin region of Ecuador. A significant portion of patients had cleft lips, palates, and noses in various pathologies and stages of repair. Some were infants with primary lips, others returned to have their palates repaired following successful lip surgery from the previous mission. A few patients developed palate fistulas following repair, and some teenagers and young adults arrived for cleft nose surgery. Following patient screening, we planned the next four operative day schedules.

We completed 61 surgical procedures in four days. Cases included cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, definitive open septo-rhinoplasty for cleft nose, thyroidectomies, tympanoplasties, a few adenotonsillectomies, and two congenital aural atresia repairs. The operative cases provided a great supplement to residency training and experience in managing cleft patients. The most meaningful part of the trip and surgical care was talking with the parents following the cases in our make-shift PACU and seeing the looks of joy, excitement, and hope on their faces.

The mission met its goals of creating accessible care to those most in need. A key factor to this successful trip was working through a well-established organization that coordinated appropriate patients for screening. The most disconcerting aspect of the care we provided is not being able to directly follow up with our patients. The FIBUSPAM clinic did arrange follow-up and we have been able to correspond with two local general surgeons and see patient photos. Working in Riobamba was enriching. I plan to participate in future medical mission trips and strongly encourage my peers to do the same. I am grateful to the AAO-HNS humanitarian grant for funding my trip.