Julius Ewald: The Man and His Famous Book – EXTENDED ONLINE VERSION

Jeremy Hornibrook, MD, FRACS In the early 19th century, the bony structure and some of the membranous structure of the inner ear were anatomically well described, but their functions unproven. A common notion was that canals were for the transmission of bone-conducted sound and for the perception of sound direction. In 1824, Pierre Flourens had published the results of his research in pigeons, in which he showed that the canals were associated with eye and head movements. Julius Ewald (1855-1921) was professor of physiology at the University of Strasbourg. His work on the inner ears of frogs, pigeons, and dogs was published in 1892, as Physiologische Untersuchungen uber das Endorgan des Nervus Octavus. Although the book is widely referred to by vestibular system investigators, few have ever seen it. A full English translation of the book was accomplished. Unfortunately, much of the book deals with ablative experiments on pigeon inner ears, but it conveys Ewald’s ingenuity in experiment and equipment design, long before the operating microscope. The most elegant and important findings are in Experiments 81 and 82. Selective cannulation of the canals enabled the application of positive and negative pressures. These correctly implied a direct connection between the canals and eye muscles except the lateral rectus, which was the only error. Ewald’s important, but perfunctory description of eye movements has come to be known as Ewald’s Laws of canal function. At the time some inconsistencies were perplexing (Ewald’s Paradox) and were not explained for another 60 years by the electron microscope. Ewald’s observations have become a quoted cornerstone of vestibular physiology and are now clinically relevant in explaining the eye movements seen in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

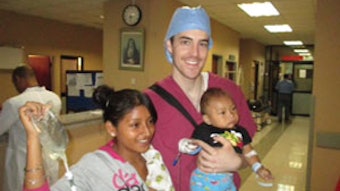

Ewald’s workbench with Westien magnifying glass (Westien’schen lupe) and the pigeon holder. Illumination is from a gas lamp reflected by a mirror. On the right is a galvanometer for heating the canals.

Ewald’s workbench with Westien magnifying glass (Westien’schen lupe) and the pigeon holder. Illumination is from a gas lamp reflected by a mirror. On the right is a galvanometer for heating the canals.Jeremy Hornibrook, MD, FRACS

In the early 19th century, the bony structure and some of the membranous structure of the inner ear were anatomically well described, but their functions unproven. A common notion was that canals were for the transmission of bone-conducted sound and for the perception of sound direction.

In 1824, Pierre Flourens had published the results of his research in pigeons, in which he showed that the canals were associated with eye and head movements.

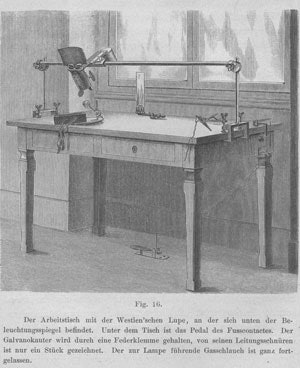

The “pneumatic hammer,” which was plastered over an opened semicircular canal, with a fine pin d, which pressed on the endolymphatic compartment of an opened canal.

The “pneumatic hammer,” which was plastered over an opened semicircular canal, with a fine pin d, which pressed on the endolymphatic compartment of an opened canal.Julius Ewald (1855-1921) was professor of physiology at the University of Strasbourg. His work on the inner ears of frogs, pigeons, and dogs was published in 1892, as Physiologische Untersuchungen uber das Endorgan des Nervus Octavus. Although the book is widely referred to by vestibular system investigators, few have ever seen it.

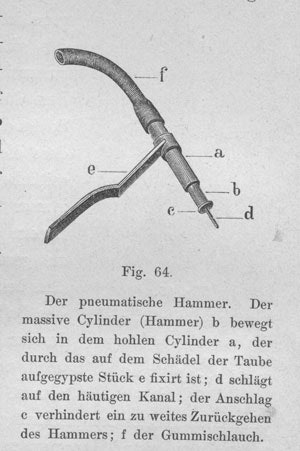

The pigeon holder with a ring for holding the pigeon’s head.

The pigeon holder with a ring for holding the pigeon’s head.A full English translation of the book was accomplished. Unfortunately, much of the book deals with ablative experiments on pigeon inner ears, but it conveys Ewald’s ingenuity in experiment and equipment design, long before the operating microscope.

The most elegant and important findings are in Experiments 81 and 82. Selective cannulation of the canals enabled the application of positive and negative pressures. These correctly implied a direct connection between the canals and eye muscles except the lateral rectus, which was the only error.

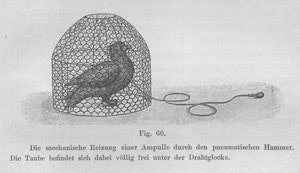

An unrestrained pigeon with a rubber hose and bulb attached to the pneumatic hammer.

An unrestrained pigeon with a rubber hose and bulb attached to the pneumatic hammer.Ewald’s important, but perfunctory description of eye movements has come to be known as Ewald’s Laws of canal function. At the time some inconsistencies were perplexing (Ewald’s Paradox) and were not explained for another 60 years by the electron microscope.

Ewald’s observations have become a quoted cornerstone of vestibular physiology and are now clinically relevant in explaining the eye movements seen in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).