Thyroid Surgical Workshop in Chikhaldara, India – EXTENDED ONLINE VERSION

Dunia Abdul-Aziz, MD Paul Konowitz, MD Madeline Randolph, BS Jackson Randolph, BS Dipti Kamani MD Gregory W. Randolph, MD In January 2014, a surgical team from the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, composed of American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery members Gregory W. Randolph, MD, Paul Konowitz, MD, Dipti V. Kamani, MD, and Dunia Abdul-Aziz, MD, teamed up with ENT surgeons from across India at the Neeti clinic in Chikhaldara, a remote mountain hospital in the outskirts of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. Surgical assistants included Madeline Randolph, a student at Providence College, and Jackson Randolph, a student recently graduated from Cornell University. Together, they embarked on an intense three-day effort not only to care for patients with goiter and thyroid disease, but also to educate junior Indian ENT surgeons on thyroid surgical technique, including neural monitoring, through hands-on experience, interactive video surgical conferencing, and formal lectures. This effort marked the 13th annual thyroid surgical workshop, a surgical camp and educational tour de force sponsored by the Rotary Club of Nagpur South and inspired and led by Madan Kapre, FRCS, DLO, a Rotarian and senior ENT surgeon in Nagpur. More than a decade ago, Dr. Kapre left his position as senior consultant in the U.K., where he had received much of his surgical training, to return home to India. He sought to facilitate access to high quality medical and surgical care across India, including rural areas. In addition, he had a goal of mentoring and educating junior ENTs in the art of thyroid surgery and the nuances of surgical decision-making. In this spirit, the Neeti clinic was created—combining Dr. Kapre’s passion for service and education. Annual surgical camps were coordinated with the support of the Rotary Club members. Senior surgeons from across India volunteered at the annual surgical camp to perform thyroidectomies and other surgeries. As each surgery took place, an intense training session was carried out simultaneously in an adjacent room as workshop attendants observed the case via streaming video. By 2014, the clinic has evolved into a stand-alone rural hospital, with two communal inpatient wards, a two-table operating room equipped with general anesthesia capacity, a pharmacy, laboratory, and full-time medical physician and nursing support. The clinic manages the perioperative care—from pre-operative evaluation to post-surgical recovery—of all patients. Affiliation with nearby larger hospitals establishes a safety measure for patients who may require higher acuity care. In addition to the thyroid surgical camp, the hospital hosts general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and ophthalmologists in similar camps addressing the medical needs of the Melghat tribal communities. We arrived to the Neeti clinic in the evening of January 12, 2014, after an uphill journey from Nagpur to Chikhaldara. Pre-operative evaluation of each patient had already been completed by the onsite physicians and Dr. Kapre’s medical team, including his wife, an anesthesiologist, and his two daughters and their husbands, who are otolaryngologists in India (Figure 1). Pre-operative ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration results had been obtained. Anesthesia risks, anemia, pregnancy, and thyroid dysfunction were obtained prior to surgery. The patients were slotted for surgery during the next two days. The start of surgery was marked by a team gathering outside the operating theater with a prayer to lord Ganesha for successful execution of the surgical camp without any obstacles. An excellent surgical team ensured the two-bed operating room ran smoothly (Figure 2). We worked side by side, and took turns with the other Indian ENT surgeons in performing the surgeries (Figure 3). The procedures were video conferenced to the hall upstairs where 40 ENT surgeons, who had made the journey from across India and as far as United Arab Emirates, were walked through the key teaching points of the procedure. Along the way, the salient aspects of management of thyroid disease were addressed both formally and informally through questions. What is the role of intraoperative nerve monitoring? How should one approach the parathyroid glands during thyroidectomy? The surgical decision making—whom to operate on and what surgery to perform—required tailoring to this particular clinical and geographic setting. Given the limited access to medical care, performing total thyroidectomies, which would commit patients to lifelong daily thyroid replacement and risk need for calcium supplementation, was limited to special clinical circumstances (papillary thyroid carcinoma in a patient for whom access to medicine was ensured). For goiter disease, surgical planning entailed preservation of residual thyroid tissue to minimize the potential for hypothyroidism. We introduced the intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) technology, pioneered at Mass Eye and Ear, and demonstrated its utility as an adjunct to anatomic identification and preservation of the nerve and as a tool for the initial nerve identification and tracing. We demonstrated the approach to troubleshooting intra-operative loss of signal. Equipment for monitoring was obtained through a grant from Medtronic and was brought from Boston to Nagpur. Nerve monitoring was easily assimilated into the workflow of the procedure and the workshop attendants acquired this skill. In addition to the delegation from Mass Eye and Ear, senior surgeons and educators from across India took turns to operate and lead the workshop discussion, including: Dr. Kapre; Alok Thakar, MS, FRCSEd, from the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi; Jyoti Dabhalkar, MS (ENT), DLO, from King Edwards Memorial (KEM) Hospital, Mumbai; Murad Lala, MD, from Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai; Ashish Varghese, MD, of Christian Medical College, Ludhiana; and Vikram Kekatpure, MD, from Mazumdar-Shaw Cancer Center, Bangalore (Figure 4). As cases were being performed in the operating room, attendants viewed the procedures in an adjacent room, stimulating active discussion about anatomic landmarks and the appropriate surgical maneuvers of each case. Through video conferencing, surgical knowledge, skills, and techniques could be disseminated across a wide spectrum of practicing surgeons in the communities from across India. Beyond a surgical mission, this workshop was educational, hoping to empower clinicians with expertise in the challenges of thyroid disease. At the completion of two operative days, the group travelled back to Nagpur for the annual thyroid Continuing Medical Education (CME) conference at The Radisson, Nagpur (Figure 5). Building on the expertise of Dr. Randolph, the course had a special focus on the utility of intraoperative nerve monitoring, stimulating interest in the applicability and potential value of incorporating this new technology into general practice in India. At the conclusion of the workshop, 12 thyroidectomies had been successfully performed for indications of large multinodular goiter with compression symptoms and for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Beyond this, 40 workshop attendants left with a nuanced understanding of the surgical management of thyroid disease. The philosophy of this mission is encompassed by the Chinese proverb: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”Beyond the patients and families who were directly influenced by the procedures, there was an equally profound emphasis on surgical education from national and global leaders in the field. These younger surgeons, equipped with the new knowledge and expertise, are the vital link in bridging the medical gap that exists across rural and urban areas, in and outside of India. The surgical camp and conference serves as a “meeting of the minds”—as a vehicle for dissemination of information and surgical know-how—carried out in a concentrated setting. This arrangement can serve as a model for global surgical education, inspiring efforts to advance beyond medical missions in which foreign surgeons operate and depart. In the end, our experience, operatively and beyond, was intensely moving and inspiring. Camaraderie among the participants of the mission was fast to form, growing from a shared commitment to excellence and safety. Out of one week grew a fellowship with the local Melghat community, ENT attendants, and Rotarians that we hope will flourish with time.

Pre-operative evaluation of patients. Patients were prescreened by the local team which included pre-operative labs and thyroid function test as well as FNA. Examination focused on the symptoms, size, and laterality of goiter.

Pre-operative evaluation of patients. Patients were prescreened by the local team which included pre-operative labs and thyroid function test as well as FNA. Examination focused on the symptoms, size, and laterality of goiter.Dunia Abdul-Aziz, MD

Paul Konowitz, MD

Madeline Randolph, BS

Jackson Randolph, BS

Dipti Kamani MD

Gregory W. Randolph, MD

In January 2014, a surgical team from the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, composed of American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery members Gregory W. Randolph, MD, Paul Konowitz, MD, Dipti V. Kamani, MD, and Dunia Abdul-Aziz, MD, teamed up with ENT surgeons from across India at the Neeti clinic in Chikhaldara, a remote mountain hospital in the outskirts of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India.

Surgical assistants included Madeline Randolph, a student at Providence College, and Jackson Randolph, a student recently graduated from Cornell University. Together, they embarked on an intense three-day effort not only to care for patients with goiter and thyroid disease, but also to educate junior Indian ENT surgeons on thyroid surgical technique, including neural monitoring, through hands-on experience, interactive video surgical conferencing, and formal lectures.

Operating theater. The two-bed operating room was fully equipped to run two cases simultaneously. Video streaming and direct conferencing allowed close up view of the surgery to the workshop.

Operating theater. The two-bed operating room was fully equipped to run two cases simultaneously. Video streaming and direct conferencing allowed close up view of the surgery to the workshop.This effort marked the 13th annual thyroid surgical workshop, a surgical camp and educational tour de force sponsored by the Rotary Club of Nagpur South and inspired and led by Madan Kapre, FRCS, DLO, a Rotarian and senior ENT surgeon in Nagpur.

More than a decade ago, Dr. Kapre left his position as senior consultant in the U.K., where he had received much of his surgical training, to return home to India. He sought to facilitate access to high quality medical and surgical care across India, including rural areas. In addition, he had a goal of mentoring and educating junior ENTs in the art of thyroid surgery and the nuances of surgical decision-making.

Surgical video conferencing. Dr. Paul Konowitz, assisted by Drs. Harsh Gupta and Neeti Kapre, leads the surgical workshop though his dissection which is being live streamed to the adjacent delegate room for discussion.

Surgical video conferencing. Dr. Paul Konowitz, assisted by Drs. Harsh Gupta and Neeti Kapre, leads the surgical workshop though his dissection which is being live streamed to the adjacent delegate room for discussion.In this spirit, the Neeti clinic was created—combining Dr. Kapre’s passion for service and education. Annual surgical camps were coordinated with the support of the Rotary Club members. Senior surgeons from across India volunteered at the annual surgical camp to perform thyroidectomies and other surgeries. As each surgery took place, an intense training session was carried out simultaneously in an adjacent room as workshop attendants observed the case via streaming video.

By 2014, the clinic has evolved into a stand-alone rural hospital, with two communal inpatient wards, a two-table operating room equipped with general anesthesia capacity, a pharmacy, laboratory, and full-time medical physician and nursing support. The clinic manages the perioperative care—from pre-operative evaluation to post-surgical recovery—of all patients.

Workshop attendants and faculty of the 13th annual workshop in Chikhaldara, India. Conducted annually, these workshops are a fertile ground for the sharing of surgical skill and knowledge among otolaryngologists in India. Each year, delegates and faculty from across India meet at this hilltop for an intensive three day surgical camp and thyroid course.

Workshop attendants and faculty of the 13th annual workshop in Chikhaldara, India. Conducted annually, these workshops are a fertile ground for the sharing of surgical skill and knowledge among otolaryngologists in India. Each year, delegates and faculty from across India meet at this hilltop for an intensive three day surgical camp and thyroid course.Affiliation with nearby larger hospitals establishes a safety measure for patients who may require higher acuity care. In addition to the thyroid surgical camp, the hospital hosts general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and ophthalmologists in similar camps addressing the medical needs of the Melghat tribal communities.

We arrived to the Neeti clinic in the evening of January 12, 2014, after an uphill journey from Nagpur to Chikhaldara. Pre-operative evaluation of each patient had already been completed by the onsite physicians and Dr. Kapre’s medical team, including his wife, an anesthesiologist, and his two daughters and their husbands, who are otolaryngologists in India (Figure 1). Pre-operative ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration results had been obtained. Anesthesia risks, anemia, pregnancy, and thyroid dysfunction were obtained prior to surgery. The patients were slotted for surgery during the next two days.

Opening ceremony—Thyroid CME in Nagpur, India. Following the surgical camp, a thyroid conference took place in Nagpur, India. This year’s conference focused on the role of recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring, which had been demonstrated in the workshop.

Opening ceremony—Thyroid CME in Nagpur, India. Following the surgical camp, a thyroid conference took place in Nagpur, India. This year’s conference focused on the role of recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring, which had been demonstrated in the workshop.The start of surgery was marked by a team gathering outside the operating theater with a prayer to lord Ganesha for successful execution of the surgical camp without any obstacles. An excellent surgical team ensured the two-bed operating room ran smoothly (Figure 2). We worked side by side, and took turns with the other Indian ENT surgeons in performing the surgeries (Figure 3).

The procedures were video conferenced to the hall upstairs where 40 ENT surgeons, who had made the journey from across India and as far as United Arab Emirates, were walked through the key teaching points of the procedure. Along the way, the salient aspects of management of thyroid disease were addressed both formally and informally through questions. What is the role of intraoperative nerve monitoring? How should one approach the parathyroid glands during thyroidectomy?

The surgical decision making—whom to operate on and what surgery to perform—required tailoring to this particular clinical and geographic setting. Given the limited access to medical care, performing total thyroidectomies, which would commit patients to lifelong daily thyroid replacement and risk need for calcium supplementation, was limited to special clinical circumstances (papillary thyroid carcinoma in a patient for whom access to medicine was ensured). For goiter disease, surgical planning entailed preservation of residual thyroid tissue to minimize the potential for hypothyroidism.

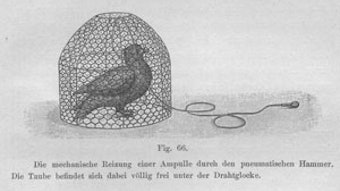

We introduced the intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) technology, pioneered at Mass Eye and Ear, and demonstrated its utility as an adjunct to anatomic identification and preservation of the nerve and as a tool for the initial nerve identification and tracing. We demonstrated the approach to troubleshooting intra-operative loss of signal. Equipment for monitoring was obtained through a grant from Medtronic and was brought from Boston to Nagpur. Nerve monitoring was easily assimilated into the workflow of the procedure and the workshop attendants acquired this skill.

In addition to the delegation from Mass Eye and Ear, senior surgeons and educators from across India took turns to operate and lead the workshop discussion, including: Dr. Kapre; Alok Thakar, MS, FRCSEd, from the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi; Jyoti Dabhalkar, MS (ENT), DLO, from King Edwards Memorial (KEM) Hospital, Mumbai; Murad Lala, MD, from Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai; Ashish Varghese, MD, of Christian Medical College, Ludhiana; and Vikram Kekatpure, MD, from Mazumdar-Shaw Cancer Center, Bangalore (Figure 4).

As cases were being performed in the operating room, attendants viewed the procedures in an adjacent room, stimulating active discussion about anatomic landmarks and the appropriate surgical maneuvers of each case. Through video conferencing, surgical knowledge, skills, and techniques could be disseminated across a wide spectrum of practicing surgeons in the communities from across India. Beyond a surgical mission, this workshop was educational, hoping to empower clinicians with expertise in the challenges of thyroid disease.

At the completion of two operative days, the group travelled back to Nagpur for the annual thyroid Continuing Medical Education (CME) conference at The Radisson, Nagpur (Figure 5). Building on the expertise of Dr. Randolph, the course had a special focus on the utility of intraoperative nerve monitoring, stimulating interest in the applicability and potential value of incorporating this new technology into general practice in India.

At the conclusion of the workshop, 12 thyroidectomies had been successfully performed for indications of large multinodular goiter with compression symptoms and for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Beyond this, 40 workshop attendants left with a nuanced understanding of the surgical management of thyroid disease.

The philosophy of this mission is encompassed by the Chinese proverb: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”Beyond the patients and families who were directly influenced by the procedures, there was an equally profound emphasis on surgical education from national and global leaders in the field.

These younger surgeons, equipped with the new knowledge and expertise, are the vital link in bridging the medical gap that exists across rural and urban areas, in and outside of India. The surgical camp and conference serves as a “meeting of the minds”—as a vehicle for dissemination of information and surgical know-how—carried out in a concentrated setting. This arrangement can serve as a model for global surgical education, inspiring efforts to advance beyond medical missions in which foreign surgeons operate and depart.

In the end, our experience, operatively and beyond, was intensely moving and inspiring. Camaraderie among the participants of the mission was fast to form, growing from a shared commitment to excellence and safety. Out of one week grew a fellowship with the local Melghat community, ENT attendants, and Rotarians that we hope will flourish with time.