Instrument Reprocessing in Otolaryngology

Patrick T. Hennessey, MD Lee D. Eisenberg, MD, MPH Ellen S. Deutsch, MD AAO-HNS Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee More than 1,000 patients were exposed to improperly reprocessed flexible fiber optic laryngoscopes in the Augusta, GA, Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center clinic in 2009. While no patients are known to have been harmed, the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of the Inspector General released a report detailing widespread improper reprocessing of these laryngoscopes, attributed to improperly trained and certified nursing staff.1 The same report documented widespread lack of adherence to reprocessing guidelines for colonoscopes at more than half of randomly inspected VA hospitals.1 This report resulted in national media attention after it was reported that six cases of HIV, 13 cases of hepatitis B, and 34 cases of hepatitis C resulted when more than 10,000 patients were exposed to contaminated scopes during colonoscopy.2 The report’s findings are sobering, and clearly illustrate the risks posed to patients by improperly reprocessed medical devices. Although most reported cases of contamination have occurred in the hospital setting, the majority of instruments used in otolaryngologists’ offices are reusable and require reprocessing in the office. Proper reprocessing of medical instrumentation is critical to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and to uphold our patients’ expectations that the devices used in their treatment are safe and clean. Indeed, a recent summit of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) focused on the issue of medical instrument reprocessing.3 The proper reprocessing of flexible endoscopes has become the focus of increasing national attention. Cross-contamination from flexible endoscopes was listed as one of the Top 10 health hazards of 2012 by the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI).4 There is little information available regarding the sterility of instruments used in the otolaryngology outpatient setting; however, a paper by Powell and colleagues in 2003 showed that as many as 17 percent of the instruments used in otolaryngology offices, such as suctions and forceps, may be contaminated with bacteria at the time they are used on patients.5 Although this was a small study, the high rate of contamination of instruments, along with the ECRI cross-contamination concerns, demonstrate a need to revisit protocols used for reprocessing instruments. There is a paucity of published literature regarding office reprocessing of otolaryngology instruments. To determine the appropriate intensity of reprocessing, instruments may be divided into three broad categories: critical, semi-critical, and noncritical (see Table). These categories are based on the type of procedure for which instruments are used. Virtually all reusable devices used in the outpatient setting by otolaryngologists, including endoscopes and handheld instruments, come into contact with the mucous membranes or non-intact skin. Therefore, these instruments are classified as semi-critical devices, requiring at least high-level decontamination to destroy all microbes and most bacterial endospores. The proper reprocessing of semi-critical instruments occurs in three phases: cleaning and decontamination, disinfection or sterilization, and storage.6 Cleaning and decontamination entails the mechanical removal of all soil from the instrument and can be accomplished by manual or machine washing. For more complex instruments, such as endoscopes with working channels, special attention must be paid to ensuring that both the visible and internal components of the instrument are properly cleaned. The removal of all soil is important so no residual organic material can shield microbes during the second step, disinfection or sterilization, during which all microbes are destroyed.7 While the choice of the specific mechanism for disinfection or sterilization should be based on the type of instrument and the information provided in manufacturer’s written instructions for use (IFU), the majority of handheld instruments used in the office setting by otolaryngologists are sterilized by steam autoclaving, while flexible and rigid scopes are usually disinfected using liquid products containing 2 percent glutaraldehyde (Cidex®), 0.2 percent peracetic acid (Steris® 20), or 0.55 percent ortho-phthalaldehyde (Cidex® OPA). Finally, the instruments should be stored in such a way as to prevent recontamination prior to being used to treat the next patient. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), endoscopes should be hung vertically, and sterilized instruments should be stored in impermeable packaging to prevent recontamination prior to use.8 Additionally, the use of disposable single-use sheaths over endoscopes has been shown to provide a similar level of sterility as chemical reprocessing. Elackattu and colleagues found that using single-use sterile sheaths with flexible fiberoptic endoscopes had a similar efficacy as chemical disinfection in preventing microbe adherence to the scopes provided the manufacturers’ sheath handling protocols were followed.9 A recent review of the literature by Collins also found that sheaths can be as effective as conventional reprocessing of flexible fiber optic laryngoscopes.10 Regardless of the method used, office-based reprocessing protocols should adhere to CDC guidelines for disinfection and sterilization of instruments,8 including having a mechanism for transportation of dirty instruments to the processing room, sorting of instruments based on type and intensity of reprocessing required, cleaning, sterilization, and finally, storage. Additionally both the CDC guidelines and the AAMI/FDA Reprocessing Summit encourage a unidirectional work flow for reprocessing to prevent recontamination of instruments after they have been sterilized, and, if possible, to have available different designated areas for each phase of reprocessing. To ensure that reprocessing guidelines are properly followed, office staff should be provided with clear instructions, proper training, and adequate space to perform reprocessing tasks. The AAMI/FDA Reprocessing Summit suggestions for training included providing formal training on device reprocessing techniques and annual continuing education to ensure proper protocols are being followed.3 To meet our patients’ expectations of being treated with clean, safe instruments it is important to adhere to established guidelines to ensure that instruments are properly cleaned for each patient. Instituting in-office protocols for reprocessing and providing proper space, equipment, and training to staff is important to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality care to our patients. References Healthcare Inspection – Use and Reprocessing of Flexible Fiberoptic Endoscopes at VA Medical Facilities. 2009, Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General: Washington, DC. O’Keefe, E., Report: VA Facilities Improperly Sterilized Colonoscopy Equipment. The Washington Post. 2009: Washington, DC. Priority Issues from the AAMI/FDA Device Reprocessing Summit. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, 2011. ERCI, Top 10 Health Technology Hazards for 2012. Health Devices. 2011.40(11). Powell, S., Perry P., Meikle D., Microbial contamination of non-disposable instruments in otolaryngology out-patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(2):122-125. McDonnell, G., Burke P., Disinfection: Is it time to reconsider Spaulding? J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(3):163-170. Muscarella, L.F., Prevention of disease transmission during flexible laryngoscopy. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(8):536-544. Rutala, W.A., Weber, D.J., Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, CDC, Editor. 2008. Elackattu, A., et al., A comparison of two methods for preventing cross-contamination when using flexible fiberoptic endoscopes in an otolaryngology clinic: disposable sterile sheaths versus immersion in germicidal liquid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2410-2416. Collins, W.O. A review of reprocessing techniques of flexible nasopharyngoscopes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(3):307-310. Table 1. Spaulding’s Classification for reprocessing of medical devices Classification Definition Level of Processing Required Critical Equipment/Devices Equipment/device that enters sterile tissues, including the vascular system Cleaning followed by sterilization Semicritical Equipment/Devices Equipment/device that comes in contact with non-intact skin or mucuous membranes, but does not penetrate them Cleaning followed by high-level disinfection Noncritical Equipment/Devices Equipment/device that touches only intact skin and not mucous membranes, or does not directly touch the patient Cleaning followed by low-level disinfection

Patrick T. Hennessey, MD

Lee D. Eisenberg, MD, MPH

Ellen S. Deutsch, MD

AAO-HNS Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee

More than 1,000 patients were exposed to improperly reprocessed flexible fiber optic laryngoscopes in the Augusta, GA, Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center clinic in 2009. While no patients are known to have been harmed, the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of the Inspector General released a report detailing widespread improper reprocessing of these laryngoscopes, attributed to improperly trained and certified nursing staff.1

The same report documented widespread lack of adherence to reprocessing guidelines for colonoscopes at more than half of randomly inspected VA hospitals.1 This report resulted in national media attention after it was reported that six cases of HIV, 13 cases of hepatitis B, and 34 cases of hepatitis C resulted when more than 10,000 patients were exposed to contaminated scopes during colonoscopy.2 The report’s findings are sobering, and clearly illustrate the risks posed to patients by improperly reprocessed medical devices.

Although most reported cases of contamination have occurred in the hospital setting, the majority of instruments used in otolaryngologists’ offices are reusable and require reprocessing in the office. Proper reprocessing of medical instrumentation is critical to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and to uphold our patients’ expectations that the devices used in their treatment are safe and clean. Indeed, a recent summit of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) focused on the issue of medical instrument reprocessing.3 The proper reprocessing of flexible endoscopes has become the focus of increasing national attention. Cross-contamination from flexible endoscopes was listed as one of the Top 10 health hazards of 2012 by the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI).4

There is little information available regarding the sterility of instruments used in the otolaryngology outpatient setting; however, a paper by Powell and colleagues in 2003 showed that as many as 17 percent of the instruments used in otolaryngology offices, such as suctions and forceps, may be contaminated with bacteria at the time they are used on patients.5 Although this was a small study, the high rate of contamination of instruments, along with the ECRI cross-contamination concerns, demonstrate a need to revisit protocols used for reprocessing instruments.

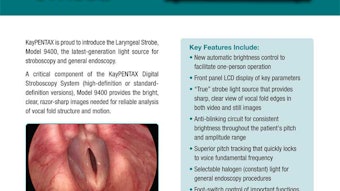

There is a paucity of published literature regarding office reprocessing of otolaryngology instruments. To determine the appropriate intensity of reprocessing, instruments may be divided into three broad categories: critical, semi-critical, and noncritical (see Table). These categories are based on the type of procedure for which instruments are used. Virtually all reusable devices used in the outpatient setting by otolaryngologists, including endoscopes and handheld instruments, come into contact with the mucous membranes or non-intact skin. Therefore, these instruments are classified as semi-critical devices, requiring at least high-level decontamination to destroy all microbes and most bacterial endospores.

The proper reprocessing of semi-critical instruments occurs in three phases: cleaning and decontamination, disinfection or sterilization, and storage.6 Cleaning and decontamination entails the mechanical removal of all soil from the instrument and can be accomplished by manual or machine washing. For more complex instruments, such as endoscopes with working channels, special attention must be paid to ensuring that both the visible and internal components of the instrument are properly cleaned.

The removal of all soil is important so no residual organic material can shield microbes during the second step, disinfection or sterilization, during which all microbes are destroyed.7 While the choice of the specific mechanism for disinfection or sterilization should be based on the type of instrument and the information provided in manufacturer’s written instructions for use (IFU), the majority of handheld instruments used in the office setting by otolaryngologists are sterilized by steam autoclaving, while flexible and rigid scopes are usually disinfected using liquid products containing 2 percent glutaraldehyde (Cidex®), 0.2 percent peracetic acid (Steris® 20), or 0.55 percent ortho-phthalaldehyde (Cidex® OPA).

Finally, the instruments should be stored in such a way as to prevent recontamination prior to being used to treat the next patient. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), endoscopes should be hung vertically, and sterilized instruments should be stored in impermeable packaging to prevent recontamination prior to use.8

Additionally, the use of disposable single-use sheaths over endoscopes has been shown to provide a similar level of sterility as chemical reprocessing. Elackattu and colleagues found that using single-use sterile sheaths with flexible fiberoptic endoscopes had a similar efficacy as chemical disinfection in preventing microbe adherence to the scopes provided the manufacturers’ sheath handling protocols were followed.9 A recent review of the literature by Collins also found that sheaths can be as effective as conventional reprocessing of flexible fiber optic laryngoscopes.10

Regardless of the method used, office-based reprocessing protocols should adhere to CDC guidelines for disinfection and sterilization of instruments,8 including having a mechanism for transportation of dirty instruments to the processing room, sorting of instruments based on type and intensity of reprocessing required, cleaning, sterilization, and finally, storage. Additionally both the CDC guidelines and the AAMI/FDA Reprocessing Summit encourage a unidirectional work flow for reprocessing to prevent recontamination of instruments after they have been sterilized, and, if possible, to have available different designated areas for each phase of reprocessing.

To ensure that reprocessing guidelines are properly followed, office staff should be provided with clear instructions, proper training, and adequate space to perform reprocessing tasks. The AAMI/FDA Reprocessing Summit suggestions for training included providing formal training on device reprocessing techniques and annual continuing education to ensure proper protocols are being followed.3

To meet our patients’ expectations of being treated with clean, safe instruments it is important to adhere to established guidelines to ensure that instruments are properly cleaned for each patient. Instituting in-office protocols for reprocessing and providing proper space, equipment, and training to staff is important to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality care to our patients.

References

- Healthcare Inspection – Use and Reprocessing of Flexible Fiberoptic Endoscopes at VA Medical Facilities. 2009, Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General: Washington, DC.

- O’Keefe, E., Report: VA Facilities Improperly Sterilized Colonoscopy Equipment. The Washington Post. 2009: Washington, DC.

- Priority Issues from the AAMI/FDA Device Reprocessing Summit. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, 2011.

- ERCI, Top 10 Health Technology Hazards for 2012. Health Devices. 2011.40(11).

- Powell, S., Perry P., Meikle D., Microbial contamination of non-disposable instruments in otolaryngology out-patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(2):122-125.

- McDonnell, G., Burke P., Disinfection: Is it time to reconsider Spaulding? J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(3):163-170.

- Muscarella, L.F., Prevention of disease transmission during flexible laryngoscopy. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(8):536-544.

- Rutala, W.A., Weber, D.J., Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, CDC, Editor. 2008.

- Elackattu, A., et al., A comparison of two methods for preventing cross-contamination when using flexible fiberoptic endoscopes in an otolaryngology clinic: disposable sterile sheaths versus immersion in germicidal liquid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2410-2416.

- Collins, W.O. A review of reprocessing techniques of flexible nasopharyngoscopes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(3):307-310.

Table 1. Spaulding’s Classification for reprocessing of medical devices

| Classification | Definition | Level of Processing Required |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Equipment/Devices | Equipment/device that enters sterile tissues, including the vascular system | Cleaning followed by sterilization |

| Semicritical Equipment/Devices | Equipment/device that comes in contact with non-intact skin or mucuous membranes, but does not penetrate them | Cleaning followed by high-level disinfection |

| Noncritical Equipment/Devices | Equipment/device that touches only intact skin and not mucous membranes, or does not directly touch the patient | Cleaning followed by low-level disinfection |