Policy Statement Updates

Policy Statement Updates The Academy currently reviews all of their policy statements on a rolling three year basis. We commenced a new review cycle in September of 2012 and are continuing to request Academy Committees’ assistance in making sure that the policy content is up to date. Rationale for Review: This review is needed because the Policy Statements have not been reviewed for several years. The Physician Payment Policy (3P) Workgroup and Health Policy team are committed to ensuring these statements are updated and useful for members. The Policy Statements for your review are those that are directly relevant to your expertise. Background: The Academy provides guidance to members through several different means including Clinical Practice Guidelines, Policy Statements, Clinical Indicators, CPT for ENT coding articles, and private payer appeal letter templates. Policy statements are generated from within AAO-HNS/F Committees. There are multiple reasons why Policy Statements are created, including: as a response to a payer payment action; to publicize our position to support a procedure for use in advocacy efforts with state and federal regulatory and federal policy or law; or to clarify the Academy’s position on certain practices within the specialty. Update Process: We have divided the policy statements into three tiers for three separate rounds of review over the course of a year (September 2012 through September 2013) taking multiple factors into account for priority including how outdated each statement is, concurrent ongoing research and guideline development, and utilization of each. After prioritization, each is assigned to clinical committee of corresponding expertise for review and update. Round 1: After an extensive first round review process by AAO-HNS Committees, the Executive Committee, and Board of Directors, the Academy has reaffirmed nine policy statements and revised 11. A new statement on Tongue Suspension was also released in December. The updates along with the new statement can be found on the Academy website as designated below. We have the revised policy statements in this article. Ambulatory Procedures—UPDATED The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recognizes the existence of lists of surgical procedures that may be appropriately performed in an ambulatory surgical center (ASC) setting. The AAO-HNS does not develop or provide these lists of otolaryngologic procedures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), however the Academy does support general standards for services covered in the ASC setting set forth in the Federal Register, Vol. 77, page 45159, July 30, 2012, and listed below: Under §416.2 and §416.166 of the regulations, subject to certain exclusions, covered surgical procedures are surgical procedures that are separately paid under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS), that would not be expected to pose a significant risk to beneficiary safety when performed in an ASC, and that would not be expected to require active medical monitoring and care at midnight following the procedure (“overnight stay”). It is important to note that there are numerous exclusions to covered services in the ASC setting that are outlined under 42 CFR §416.166 and listed below: General exclusions. Notwithstanding paragraph of this section, covered surgical procedures do not include those surgical procedures that— Generally result in extensive blood loss; Require major or prolonged invasion of body cavities; Directly involve major blood vessels; Are generally emergent or life-threatening in nature; Commonly require systemic thrombolytic therapy; Are designated as requiring inpatient care under § 419.22(n) of this subchapter; Can only be reported using a CPT unlisted surgical procedure code; or Are otherwise excluded under § 411.15 of this subchapter. Botulinum Toxin Treatment—UPDATED Section I. Treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia (Laryngeal Dystonia) The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Inc. (“AAO-HNS”) considers Botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of spasmodic dysphonia and it may be offered as primary therapy for this disorder. Section II. Botox Treatment for Other Head And Neck Dystonias A. Blepharospasm The AAO-HNS considers botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of blepharospasm and it may be offered as a primary form of therapy. Botulinum toxin has been approved as a safe and effective treatment of blepharospasm by the FDA. B. Cervical Dystonia (Spasmodic Torticollis) The AAO-HNS considers botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of cervical dystonia. There is some controversy as to whether botulinum toxin or pharmacotherapy should be offered as primary therapy. The benefit from botulinum toxin outweighs that of pharmacotherapy in many cases, certainly for the treatment of rotational cervical dystonia, or cervical dystonia associated with severe pain. In cases where there is inadequate response with pharmacotherapy, or there are intervening side effects, treatment with botulinum toxin may be offered. C. Orolinguomandibular Dystonia 1. The AAO-HNS states that local injections of botulinum toxin into the masseter and temporalis muscles for jaw-closing, and pterygoid and digastic muscles for jaw-opening dystonia is established as a safe and effective modality for managing this disorder. 2. Considering the difficulty of the procedure in treating complicated jaw deviations and jaw opening, this form of treatment is limited to patients who have failed more conservative therapies. However, the benefit has been dramatic for some in this select group. Use of botulinum toxin for jaw-opening and deviation dystonia, injecting toxin into the pterygoid and digrastic muscles is promising, but additional experience is needed. 3. Lingual dystonia may be effectively treated with botulinum toxin, but there is a significant risk of dysphagia. Botulinum toxin therapy is investigational for this indication. D. Hemifacial Spasm (HFS) and/or Synkinesis The AAO-HNS considers local injections of botulinum toxin into facial muscles a safe and effective modality in treating hemifacial spasm and/or synkinesis. This modality of therapy may be offered as primary therapy in managing the condition. Botulinum toxin can be particularly helpful in treating synkinesis to reestablish facial symmetry following a facial nerve paralysis. E. Neurogenic Laryngeal Stridor The AAO-HNS considers local injections of botulinum toxin into laryngeal muscles an effective modality in treating neurogenic laryngeal stridor. This modality of therapy may be offered as primary therapy in managing the condition. While it is generally very safe, the nature of the disorder and the potential contributing problems such as stridor and aspiration should be considered in its case. F. Frye’s Syndrome Botulinum toxin can be applied to patients for treatment of Frye’s Syndrome and gustatory sweating related to autonomic dysfunction. Section III. Treatment of Other Conditions A. Facial Dynamic Rhytids Botulinum toxin can be applied to patients for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows. B. Recalcitrant Hyperfuntional Voice Disorders Botulinum toxin can be injected for management of recalcitrant muscular tension dysphonia, mutational dysphonia, and other hyperfunctional voice disorders (i.e., vocal fold granulomas or traumatic mucosal injury) that do not resolve with more traditional voice therapy methods and other more conservative medical measures. C. Cricoppharyngeus Muscle Hypertonicity In select patients, botulinum toxin may be useful in the treatment of dysphagia due to hypertonicity of the cricopharyngeus muscle. Botulinum toxin can also be applied to patients with post-laryngectomy cricopharyngeus muscle hypertonicity causing difficulty with the use of voice prostheses. Debridement of the Sinus Cavity after ESS—UPDATED Debridement of the sinus cavity is a procedure commonly performed following endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). It involves transnasal insertion of the endoscope for visualization and parallel insertion of various instruments for the purpose of removal of postsurgical crusting, residua of dissolvable spacers, coagulum, early synechiae, or devitalized bone or mucosa. It may also be utilized to remove crusts or debris in patients with longstanding chronic sinusitis with persistent sinonasal inflammation who have undergone sinus surgery in the past. It is performed under local or general anesthesia in a suitably equipped office or operating room, depending on the clinical circumstances of the case. It is the position of the Academy that postoperative debridement aids healing and optimizes the ability to achieve open, functional sinus cavities. This also facilitates optimal instillation of topical therapies and saline irrigations, long-term disease surveillance, and endoscopically-derived cultures. Similar improvement in control of inflammation and secondary infection is obtained by debridement in other subtypes of chronic sinusitis patients; particularly in recurrent/persistent bacterial infections and/or fungal sinusitis. Debridement may also be required in patients with chronic crusting in the setting of previous endoscopic tumor surgery and/or paranasal sinus radiation. The frequency with which the above mentioned procedure should be performed is a clinical judgement best made by the surgeon and determined on a case-by-case basis, with the patient’s clinical interests as the criteria of need. Setting an arbitrary limit on the number of debridements does not account for variability between patients in the healing process or severity of disease and can significantly jeopardize the quality of care that patients receive and negatively affect the overall outcome of ESS. The Medicare fee schedule, the source for the concept of global periods, clearly assigns zero follow-up days to the 31237 code and most ESS procedures (several have a 10 day period: 31239 and 31290-31294). The reason for this assignment is that in the initial formulation of the relative value units for ESS, need for debridement of the sinus cavity was noted to vary greatly depending on the individual surgical case. ESS relative value units were developed with this exclusion of debridements factored into their overall weight: ESS code values do not include the work, risk, judgement, and skill necessary for this separate procedure. Medicare work values assigned to the various codes for ESS took into account all of these factors. Haphazardly assigning lower work-valued codes in the place of 31237 as well as tampering with the Medicare global periods assigned, leads to the skewing of several of the key elements that were arrived at to produce fairness and equitable payments for the work done. This results in incorrectly lowered payments, inconsistent with the level, volume, and intensity of the work performed. Insurance companies that profess to use Medicare approaches to reimbursements should use all of the critical elements of those formulations to be consistent with the work values and payment rules inherent in the Medicare concepts mentioned. Sinus surgery is unilateral in nature as are debridements done thereafter. Payments for these procedures should be also. Adopted 10-18-12 Guidelines are not a substitute for the experience and judgment of a physician and are developed to enhance the physicians’ ability to practice evidence-based medicine. Foreign Bodies of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract—UPDATED Board certified members of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, by virtue of their training, are qualified to manage foreign bodies of the upper aerodigestive tract in adults and children. Whenever experienced physicians, appropriately trained support personnel, properly sized equipment, and appropriate post-surgical patient care are available, these cases should ideally be managed at the closest available facility. Head and Neck Surgery—UPDATED To become board certified, an otolaryngologist has to complete a rigorous training program. Following one year training in general surgery, an additional five years of residency training in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery is required to be considered eligible to apply to sit for the specialty board examination in otolaryngology. During the training years, residents in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery should learn to manage the full spectrum of benign and malignant disorders involving the head and neck while also learning techniques of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Implantable Hearing Devices—UPDATED The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Inc. considers the implantation of a percutaneous or transcutaneous bone conduction hearing device, placement of a bone conduction oral appliance, and implantation of a semi-implantable or totally implantable hearing device to be acceptable surgical procedures for the relief of hearing impairment when performed by a qualified otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon or other qualified healthcare professional. Use of any device must adhere to the restrictions and guidelines specified by the appropriate governing agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States and other similar regulatory agencies in countries other than the United States. Micropressure Therapy—UPDATED The Equilibrium Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and the Board of Directors of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery have reviewed the literature with respect to micropressure therapy for Meniere’s disease. We find that there is convincing and well-controlled medical evidence to support the use of micropressure therapy (such as the Meniett device) in certain cases of Meniere’s disease. Micropressure therapy can be used as a second level therapy when medical treatment has failed. The device represents a largely non-surgical therapy that should be available as one of the many treatments for Meniere’s disease. Nasal Surgery and OSAS—UPDATED Nasal surgery is a beneficial modality for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Nasal surgery can facilitate the treatment of OSA using CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure). Nasal resistance or obstruction is highly related to CPAP non-acceptance where for each 0.1 Pa/cm3/s increase in resistance the odds ratio of non-acceptance increases 1.48 fold (Sugiura 2007, level 2). Nasal surgery lowers nasal resistance and Nakata & coworkers (2005, level 3) showed that using septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction for CPAP non-adherent patients, there was a reduction in nasal resistance from 0.57 to 0.16 Pa/cm3/s and postoperatively, all patients became CPAP adherent. Nasal surgery may lower CPAP pressures by 2-3cm H2O in level 4 studies (Friedman 2000, Zonato 2006 ) Nasal surgery may facilitate the treatment of OSA using oral appliances. Non-responders to oral appliance therapy have higher nasal resistance compared with responders (Zeng 2008, level 2). Similarly, in a study of 630 patients treated with mandibular advancement devices (Marklund 2004, level 2), women with complaints of nasal obstruction had an odds radio for successful treatment of only 0.1. Since nasal surgery lowers nasal airway resistance, oral appliance therapy may be facilitated in subjects with nasal obstruction. Nasal surgery can improve quality of life in patients with sleep apnea in level 3 & 4 studies. With nasal surgery, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), has been shown to decline from levels associated with excessive sleepiness (>=10) to levels consistent with normal function (Verse 2002, Nakata 2005, Li 2008). SF-36 scores of OSA patients significantly improved in the role physical, emotional, vitality, social functioning, generic health and mental health domains, following nasal surgery (Li 2008). Nasal surgery as the sole intervention effectively treats OSA in a subset of patients. The overall success rate is about 17 percent for Apnea hypopnea index reduction of 50 percent and to less than 95 percent). Only 27 percent of the children had complete resolution of OSA (AHI < 1 total sleep time) while 21.6 percent had an AHI>5/hr TST. Surgical success was variable and depended upon outcome measures selected. So success is as low as 27 percent (AHI of < 1) or as high as 78 percent (AHI 5/hr TST. An analysis of factors that were associated with an elevated post-operative AHI in order of influence were older than seven years, elevated BMI, presence of asthma, and more severe OSA pre-operatively. In most patients with moderate to severe OSA, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first line treatment. Successful long-term treatment of OSA with CPAP is difficult to achieve and fewer than 50 percent of patients on CPAP are adequately treated, as defined by four hours of use 70 percent of nights (Weaver, TE, Level 2 evidence and Kribbs, NB, Level 2 evidence). Other treatment options must be available to patients with OSAS. Surgical procedures may be considered as a secondary treatment for OSA when the outcome of PAP therapy is inadequate, such as when the patient is intolerant of CPAP, or CPAP therapy is unable to eliminate OSA (Consensus). Surgery may also be considered as a secondary therapy when there is an inadequate treatment outcome with an oral appliance (OA), when the patient is intolerant of the OA, or the OA therapy provides unacceptable improvement of clinical outcomes of OSA (Consensus). Surgery may also be considered as an adjunct therapy when obstructive anatomy or functional deficiencies compromise other therapies or to improve tolerance of other OSA treatments (Consensus)(Epstein, EJ). Surgery for OSAS has been shown to improve important clinical outcomes including survival and quality of life (Weaver, EM. Level 2 evidence). References Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, Mitchell RB, Promchiarak J, Simakajornboon N, Kaditis AG, Splaingard D, Splaingard M, Brooks LJ, Marcus CL, Sin S, Arens R, Verhulst SL, Gozal D. Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Sep 1;182(5):676-83. Epub 2010 May 6. PubMed PMID: 20448096. Epstein, EJ (Chair), Kristo, D, Strollo, Jr. PJ. Clinical Guidelines for the Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 5(3):263-79, 2009. Brietzke S, Gallagher D. The effectiveness of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: A meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134(6), 979-984, 2006. Weaver TE, Grunstein RR; Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 5(2):173-8, 2008. Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 147:887-95.1993. Weaver EM, Maynard C, Yueh B. Survival of veterans with sleep apnea: continuous positive airway pressure versus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 130(6):659-65. 2004. Cochlear Implants and Meningitis Vaccination—UPDATED What you should know Children with cochlear implants are more likely to get bacterial meningitis than children without cochlear implants. In addition, some children who are candidates for cochlear implants have inner ear anatomic abnormalities that may increase their risk for meningitis. Because children with cochlear implants are at increased risk for pneumococcal meningitis, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that they receive pneumococcal vaccination on the same schedule that is recommended for other groups at increased risk for invasive pneumococcal disease. Recommendations for the timing and type of pneumococcal vaccination vary with age and vaccination history and should be discussed with a healthcare provider. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for individuals with cochlear implants. These recommendations can be viewed in detail on the CDC website: (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5909a2.htm). Children who have cochlear implants or are candidates for cochlear implants should receive PCV13. PCV13 is now recommended routinely for all infants and children (see Table 2 in the CDC March 12, 2010 MMWR issue located at the above website for the number of doses and dosing schedule). Older children with cochlear implants (from age two years through age five) should receive two doses of PCV13 if they have not received any doses of PCV7 or PCV13 previously. If they have already completed the four-dose PCV7 series, they should receive one dose of PCV13 through age 71 months. Children six through 18 years of age with cochlear implants may receive a single dose of PCV13 regardless of whether they have previously received PCV7 or the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) (Pneumovax®). In addition to receiving PCV13, children with cochlear implants should receive one dose of PPSV23 at age two years or older and after completing all recommended doses of PCV13. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for adults with cochlear implants. These recommendations can be viewed in detail on the CDC website: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6140a4.htm. Adult patients (=19 yrs of age) who are candidates for a cochlear implant and those who have received a cochlear implant should be given a single dose of PCV13 followed by a PPSV23 at least eight weeks later. A second dose of PPSV23 is recommended for those 65 years old and older. For those adults who previously have received =1 doses of PPSV23 should be given a PCV13 dose =1 year after the last PPSV23 dose was received. For those who require additional doses of PPSV23, the first such dose should be given no sooner than eight weeks after PCV13 and at least five years after the most recent dose of PPSV23. For both children and adults, the vaccination schedule should be completed at two weeks or more before surgery. Additional Facts According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as of April 2009, approximately 188,000 people worldwide have received cochlear implants. In the United States, roughly 41,500 adults and 25,500 children have received them. In the U.S., there are 122 known reports of meningitis in patients who have received cochlear implants with 64 percent of these cases having occurred in children. Meningitis is an infection of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. There are two main types of meningitis, viral and bacterial. Bacterial meningitis is the more serious type and the type that has been reported in individuals with cochlear implants. The symptoms, treatment, and outcomes may differ depending on the cause of the meningitis. The vaccines available in the United States that protect against most bacteria that cause meningitis are: 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) (Prevnar 13®) 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV) (Pneumovax®) Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate (Hib) Tetravalent (A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal conjugate (Menactra® and Menveo®) Tetravalent (A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal polysaccharide (Menomune®) Meningitis in individuals with cochlear implants is most commonly caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus). Children with cochlear implants are more likely to get pneumococcal meningitis than children without cochlear implants. There is no evidence that children with cochlear implants are more likely to get meningococcal meningitis, caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitides, than children without cochlear implants. Healthcare providers should follow the CDC immunization guidelines for routine meningococcal vaccination. The Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine is not routinely recommended for those five years old or older, since most older children and adults are already immune to Hib. Available information does not suggest that older children and adults with cochlear implants require the Hib vaccine. However, the Hib vaccine can be given to older children and adults who have never received it. Children younger than age five should receive the Hib vaccine as a routine protection, according to the CDC guidelines for childhood immunizations. Most children born after 1990 have received the Hib vaccine as infants. Healthcare providers (family physicians, pediatricians, and otolaryngologists) and families should review the vaccination records of current and prospective cochlear implant recipients to ensure that all recommended vaccinations are up to date After beginning in the Fall of 2012 with a review of those policies which were the most out of date and most highly utilized first, we have progressed to the second round of review. In 2013, the Academy will be continuing to request Academy Committees’ assistance for second and third round reviews to ensure that the policy content is up to date. If you have any questions regarding the policy statement update process, please email healthpolicy@entnet.org. The Academy would like to extend a special thank you to the hard work of the following committees for contributing their clinical expertise during the first round of policy statement reviews: The Physician Payment Policy Workgroup (3P) The Airway and Swallowing Committee The Equilibrium Committee The Head and Neck Surgery Education Committee The Hearing Committee The Imaging Committee The Implantable Hearing Devices Committee The Medical Devices and Drugs Committee The Pediatric Otolaryngology Committee The Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Committee The Rhinology and Paranasal Sinus Committee The Sleep Disorders Committee The Voice Committee

Policy Statement Updates

The Academy currently reviews all of their policy statements on a rolling three year basis. We commenced a new review cycle in September of 2012 and are continuing to request Academy Committees’ assistance in making sure that the policy content is up to date.

Rationale for Review:

- This review is needed because the Policy Statements have not been reviewed for several years.

- The Physician Payment Policy (3P) Workgroup and Health Policy team are committed to ensuring these statements are updated and useful for members.

- The Policy Statements for your review are those that are directly relevant to your expertise.

Background:

- The Academy provides guidance to members through several different means including Clinical Practice Guidelines, Policy Statements, Clinical Indicators, CPT for ENT coding articles, and private payer appeal letter templates.

- Policy statements are generated from within AAO-HNS/F Committees. There are multiple reasons why Policy Statements are created, including: as a response to a payer payment action; to publicize our position to support a procedure for use in advocacy efforts with state and federal regulatory and federal policy or law; or to clarify the Academy’s position on certain practices within the specialty.

Update Process:

- We have divided the policy statements into three tiers for three separate rounds of review over the course of a year (September 2012 through September 2013) taking multiple factors into account for priority including how outdated each statement is, concurrent ongoing research and guideline development, and utilization of each. After prioritization, each is assigned to clinical committee of corresponding expertise for review and update.

Round 1:

- After an extensive first round review process by AAO-HNS Committees, the Executive Committee, and Board of Directors, the Academy has reaffirmed nine policy statements and revised 11. A new statement on Tongue Suspension was also released in December.

- The updates along with the new statement can be found on the Academy website as designated below. We have the revised policy statements in this article.

Ambulatory Procedures—UPDATED

The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recognizes the existence of lists of surgical procedures that may be appropriately performed in an ambulatory surgical center (ASC) setting. The AAO-HNS does not develop or provide these lists of otolaryngologic procedures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), however the Academy does support general standards for services covered in the ASC setting set forth in the Federal Register, Vol. 77, page 45159, July 30, 2012, and listed below:

Under §416.2 and §416.166 of the regulations, subject to certain exclusions, covered surgical procedures are surgical procedures that are separately paid under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS), that would not be expected to pose a significant risk to beneficiary safety when performed in an ASC, and that would not be expected to require active medical monitoring and care at midnight following the procedure (“overnight stay”).

It is important to note that there are numerous exclusions to covered services in the ASC setting that are outlined under 42 CFR §416.166 and listed below:

General exclusions. Notwithstanding paragraph of this section, covered surgical procedures do not include those surgical procedures that—

- Generally result in extensive blood loss;

- Require major or prolonged invasion of body cavities;

- Directly involve major blood vessels;

- Are generally emergent or life-threatening in nature;

- Commonly require systemic thrombolytic therapy;

- Are designated as requiring inpatient care under § 419.22(n) of this subchapter;

- Can only be reported using a CPT unlisted surgical procedure code; or

- Are otherwise excluded under § 411.15 of this subchapter.

Botulinum Toxin Treatment—UPDATED

Section I. Treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia (Laryngeal Dystonia)

The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Inc. (“AAO-HNS”) considers Botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of spasmodic dysphonia and it may be offered as primary therapy for this disorder.

Section II. Botox Treatment for Other Head And Neck Dystonias A. Blepharospasm

The AAO-HNS considers botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of blepharospasm and it may be offered as a primary form of therapy. Botulinum toxin has been approved as a safe and effective treatment of blepharospasm by the FDA.

B. Cervical Dystonia (Spasmodic Torticollis) The AAO-HNS considers botulinum toxin a safe and effective modality for the treatment of cervical dystonia. There is some controversy as to whether botulinum toxin or pharmacotherapy should be offered as primary therapy. The benefit from botulinum toxin outweighs that of pharmacotherapy in many cases, certainly for the treatment of rotational cervical dystonia, or cervical dystonia associated with severe pain. In cases where there is inadequate response with pharmacotherapy, or there are intervening side effects, treatment with botulinum toxin may be offered.

C. Orolinguomandibular Dystonia 1. The AAO-HNS states that local injections of botulinum toxin into the masseter and temporalis muscles for jaw-closing, and pterygoid and digastic muscles for jaw-opening dystonia is established as a safe and effective modality for managing this disorder.

2. Considering the difficulty of the procedure in treating complicated jaw deviations and jaw opening, this form of treatment is limited to patients who have failed more conservative therapies. However, the benefit has been dramatic for some in this select group. Use of botulinum toxin for jaw-opening and deviation dystonia, injecting toxin into the pterygoid and digrastic muscles is promising, but additional experience is needed.

3. Lingual dystonia may be effectively treated with botulinum toxin, but there is a significant risk of dysphagia. Botulinum toxin therapy is investigational for this indication.

D. Hemifacial Spasm (HFS) and/or Synkinesis

The AAO-HNS considers local injections of botulinum toxin into facial muscles a safe and effective modality in treating hemifacial spasm and/or synkinesis. This modality of therapy may be offered as primary therapy in managing the condition. Botulinum toxin can be particularly helpful in treating synkinesis to reestablish facial symmetry following a facial nerve paralysis.

E. Neurogenic Laryngeal Stridor

The AAO-HNS considers local injections of botulinum toxin into laryngeal muscles an effective modality in treating neurogenic laryngeal stridor. This modality of therapy may be offered as primary therapy in managing the condition. While it is generally very safe, the nature of the disorder and the potential contributing problems such as stridor and aspiration should be considered in its case.

F. Frye’s Syndrome

Botulinum toxin can be applied to patients for treatment of Frye’s Syndrome and gustatory sweating related to autonomic dysfunction.

Section III. Treatment of Other Conditions

A. Facial Dynamic Rhytids

Botulinum toxin can be applied to patients for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows.

B. Recalcitrant Hyperfuntional Voice Disorders

Botulinum toxin can be injected for management of recalcitrant muscular tension dysphonia, mutational dysphonia, and other hyperfunctional voice disorders (i.e., vocal fold granulomas or traumatic mucosal injury) that do not resolve with more traditional voice therapy methods and other more conservative medical measures.

C. Cricoppharyngeus Muscle Hypertonicity

In select patients, botulinum toxin may be useful in the treatment of dysphagia due to hypertonicity of the cricopharyngeus muscle. Botulinum toxin can also be applied to patients with post-laryngectomy cricopharyngeus muscle hypertonicity causing difficulty with the use of voice prostheses.

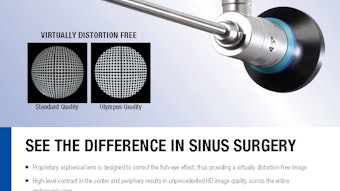

Debridement of the Sinus Cavity after ESS—UPDATED

Debridement of the sinus cavity is a procedure commonly performed following endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). It involves transnasal insertion of the endoscope for visualization and parallel insertion of various instruments for the purpose of removal of postsurgical crusting, residua of dissolvable spacers, coagulum, early synechiae, or devitalized bone or mucosa. It may also be utilized to remove crusts or debris in patients with longstanding chronic sinusitis with persistent sinonasal inflammation who have undergone sinus surgery in the past. It is performed under local or general anesthesia in a suitably equipped office or operating room, depending on the clinical circumstances of the case.

It is the position of the Academy that postoperative debridement aids healing and optimizes the ability to achieve open, functional sinus cavities. This also facilitates optimal instillation of topical therapies and saline irrigations, long-term disease surveillance, and endoscopically-derived cultures.

Similar improvement in control of inflammation and secondary infection is obtained by debridement in other subtypes of chronic sinusitis patients; particularly in recurrent/persistent bacterial infections and/or fungal sinusitis. Debridement may also be required in patients with chronic crusting in the setting of previous endoscopic tumor surgery and/or paranasal sinus radiation.

The frequency with which the above mentioned procedure should be performed is a clinical judgement best made by the surgeon and determined on a case-by-case basis, with the patient’s clinical interests as the criteria of need. Setting an arbitrary limit on the number of debridements does not account for variability between patients in the healing process or severity of disease and can significantly jeopardize the quality of care that patients receive and negatively affect the overall outcome of ESS.

The Medicare fee schedule, the source for the concept of global periods, clearly assigns zero follow-up days to the 31237 code and most ESS procedures (several have a 10 day period: 31239 and 31290-31294). The reason for this assignment is that in the initial formulation of the relative value units for ESS, need for debridement of the sinus cavity was noted to vary greatly depending on the individual surgical case. ESS relative value units were developed with this exclusion of debridements factored into their overall weight: ESS code values do not include the work, risk, judgement, and skill necessary for this separate procedure.

Medicare work values assigned to the various codes for ESS took into account all of these factors. Haphazardly assigning lower work-valued codes in the place of 31237 as well as tampering with the Medicare global periods assigned, leads to the skewing of several of the key elements that were arrived at to produce fairness and equitable payments for the work done. This results in incorrectly lowered payments, inconsistent with the level, volume, and intensity of the work performed.

Insurance companies that profess to use Medicare approaches to reimbursements should use all of the critical elements of those formulations to be consistent with the work values and payment rules inherent in the Medicare concepts mentioned.

Sinus surgery is unilateral in nature as are debridements done thereafter. Payments for these procedures should be also. Adopted 10-18-12 Guidelines are not a substitute for the experience and judgment of a physician and are developed to enhance the physicians’ ability to practice evidence-based medicine.

Foreign Bodies of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract—UPDATED

Board certified members of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, by virtue of their training, are qualified to manage foreign bodies of the upper aerodigestive tract in adults and children. Whenever experienced physicians, appropriately trained support personnel, properly sized equipment, and appropriate post-surgical patient care are available, these cases should ideally be managed at the closest available facility.

Head and Neck Surgery—UPDATED

To become board certified, an otolaryngologist has to complete a rigorous training program. Following one year training in general surgery, an additional five years of residency training in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery is required to be considered eligible to apply to sit for the specialty board examination in otolaryngology. During the training years, residents in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery should learn to manage the full spectrum of benign and malignant disorders involving the head and neck while also learning techniques of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Implantable Hearing Devices—UPDATED

The American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Inc. considers the implantation of a percutaneous or transcutaneous bone conduction hearing device, placement of a bone conduction oral appliance, and implantation of a semi-implantable or totally implantable hearing device to be acceptable surgical procedures for the relief of hearing impairment when performed by a qualified otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon or other qualified healthcare professional. Use of any device must adhere to the restrictions and guidelines specified by the appropriate governing agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States and other similar regulatory agencies in countries other than the United States.

Micropressure Therapy—UPDATED

The Equilibrium Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and the Board of Directors of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery have reviewed the literature with respect to micropressure therapy for Meniere’s disease.

We find that there is convincing and well-controlled medical evidence to support the use of micropressure therapy (such as the Meniett device) in certain cases of Meniere’s disease. Micropressure therapy can be used as a second level therapy when medical treatment has failed. The device represents a largely non-surgical therapy that should be available as one of the many treatments for Meniere’s disease.

Nasal Surgery and OSAS—UPDATED

Nasal surgery is a beneficial modality for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Nasal surgery can facilitate the treatment of OSA using CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure). Nasal resistance or obstruction is highly related to CPAP non-acceptance where for each 0.1 Pa/cm3/s increase in resistance the odds ratio of non-acceptance increases 1.48 fold (Sugiura 2007, level 2). Nasal surgery lowers nasal resistance and Nakata & coworkers (2005, level 3) showed that using septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction for CPAP non-adherent patients, there was a reduction in nasal resistance from 0.57 to 0.16 Pa/cm3/s and postoperatively, all patients became CPAP adherent. Nasal surgery may lower CPAP pressures by 2-3cm H2O in level 4 studies (Friedman 2000, Zonato 2006 )

Nasal surgery may facilitate the treatment of OSA using oral appliances. Non-responders to oral appliance therapy have higher nasal resistance compared with responders (Zeng 2008, level 2). Similarly, in a study of 630 patients treated with mandibular advancement devices (Marklund 2004, level 2), women with complaints of nasal obstruction had an odds radio for successful treatment of only 0.1. Since nasal surgery lowers nasal airway resistance, oral appliance therapy may be facilitated in subjects with nasal obstruction.

Nasal surgery can improve quality of life in patients with sleep apnea in level 3 & 4 studies. With nasal surgery, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), has been shown to decline from levels associated with excessive sleepiness (>=10) to levels consistent with normal function (Verse 2002, Nakata 2005, Li 2008). SF-36 scores of OSA patients significantly improved in the role physical, emotional, vitality, social functioning, generic health and mental health domains, following nasal surgery (Li 2008).

Nasal surgery as the sole intervention effectively treats OSA in a subset of patients. The overall success rate is about 17 percent for Apnea hypopnea index reduction of 50 percent and to less than <20/hour, as summarized in a review by Verse & coworkers (2003). This is based on case series studies cited in Verse (2003), Morinaga (2009) Series (1992), and in a randomized, placebo controlled study by Koutsourelakis (2008).

References

- Sugiura T, Noda A, Nakata S, Yasuda Y, Soga T, Miyata S, Nakai S, Koike Y. Influence of nasal resistance on initial acceptance of continuous positive airway pressure in treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2007;74(1):56-60.PMID: 16299414.

- Nakata S, Noda A, Yasuma F, Morinaga M, Sugiura M, Katayama N, Sawaki M, Teranishi M, Nakashima T. Effects of nasal surgery on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome with nasal obstruction. Am J Rhinol. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):59-63. PMID: 18284861.

- Friedman M, Tanyeri H, Lim JW, Landsberg R, Vaidyanathan K, Caldarelli D. Effect of improved nasal breathing on obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Jan;122(1):71-4. PMID: 10629486.

- Zonato AI, Bittencourt LR, Martinho FL, Gregório LC, Tufik S. Upper airway surgery: the effect on nasal continuous positive airway pressure titration on obstructive sleep apnea patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 May;263(5):481-6. PMID: 16450157.

- Zeng B, Ng AT, Qian J, Petocz P, Darendeliler MA, Cistulli PA. Influence of nasal resistance on oral appliance treatment outcome in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2008 Apr 1;31(4):543-7. PMID: 18457242.

- Marklund M, Stenlund H, Franklin KA. Mandibular advancement devices in 630 men and women with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: tolerability and predictors of treatment success. Chest. 2004 Apr;125(4):1270-8. PMID: 15078734.

- Verse T, Maurer JT, Pirsig W. Effect of nasal surgery on sleep-related breathing disorders. Laryngoscope. 2002 Jan;112(1):64-8. PMID: 11802040.

- Li HY, Lin Y, Chen NH, Lee LA, Fang TJ, Wang PC. Improvement in quality of life after nasal surgery alone for patients with obstructive sleep apnea and nasal obstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 Apr;134(4):429-33. PMID: 18427011.

- Verse T, Pirsig W. Impact of impaired nasal breathing on sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2003 Jun;7(2):63-76. PMID: 12861486.

- Morinaga M, Nakata S, Yasuma F, Noda A, Yagi H, Tagaya M, Sugiura M, Teranishi M, Nakashima T. Pharyngeal morphology: a determinant of successful nasal surgery for sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2009 May;119(5):1011-6. PMID: 19301414.

- Sériès F, St Pierre S, Carrier G. Effects of surgical correction of nasal obstruction in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Nov;146(5 Pt 1):1261-5. PMID: 1443882.

- Koutsourelakis I, Georgoulopoulos G, Perraki E, Vagiakis E, Roussos C, Zakynthinos SG. Randomised trial of nasal surgery for fixed nasal obstruction in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2008 Jan;31(1):110-7. PMID: 17898015.

- Victores AJ, Takashima M. Effects of nasal surgery on the upper airway: A drug-induced sleep endoscopy study. Laryngoscope. 2012 Aug 8. doi: 10.1002/lary.23584. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22886986.

- Sufioglu M, Ozmen OA, Kasapoglu F, Demir UL, Ursavas A, Erisen L, Onart S. The efficacy of nasal surgery in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a prospective clinical study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Feb;269(2):487-94. Epub 2011 Jul 15. PubMed PMID: 21761192.

- Friedman M, Maley A, Kelley K, Leesman C, Patel A, Pulver T, Joseph N, Catli T. Impact of nasal obstruction on obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011 Jun;144(6):1000-4. Epub 2011 Mar 3. PubMed PMID: 21493302.

- Li H, Wang PC, Chen YP, Lee LA, Fang TJ, Lin HC. Critical appraisal and meta-analysis of nasal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010 Dec 17. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 21172121.

The Roles of Flexible Laryngoscopy / Videostroboscopy—UPDATED

The Roles of Flexible Laryngoscopy Videostroboscopy in the Office Evaluation and Management of Patients with Otolaryngologic Disorders.

Flexible and telescopic diagnostic laryngoscopy (31575) and flexible and/or rigid videostroboscopy (31579) are well established diagnostic procedures that are medically indicated for the diagnosis of voice, swallowing, and airway disorders.Each procedure requires the application of distinct endoscopy skills, training and judgment. These endoscopic procedures offer unique information in the functional and anatomic assessment of the upper airway. In most cases, these examinations can be performed in the office without taking the patient to the operating room or the endoscopy suite. These procedures are effective in diagnosis and management of otolaryngologic disorders and they are not investigational. Some patients may require one or more of these diagnostic procedures performed individually or sequentially. The extended nature of examination of the structure and function of the upper aerodigestive tract is often comprehensive and complex. The endoscopic evaluation of the upper airway should not be considered part of the routine office examination.

- Flexible laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy should not be considered a routine part of an office visit.

- Flexible laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy should not be required to be done as a separate return visit.

- Flexible laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy should not be mandated to be performed in a separate endoscopy suite or outpatient surgery center in order to be reimbursed.

Clearly defined clinical indicators based on ICD-9 diagnostic code groups have been developed in the literature to support the above positions.

Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea—UPDATED

Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea—Overview

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a common disorder involving collapse of the upper airway during sleep. This repetitive collapse results in sleep fragmentation, hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and increased sympathetic activity. As specialists in upper airway anatomy, physiology, and surgery, otolaryngologists are uniquely qualified to treat patients with OSA. In the Clinical Guidelines for Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults, it is recommended that evaluation for primary surgical treatment be considered in select patients who have severe obstructing anatomy that is surgically correctible (e.g., tonsillar hypertrophy obstructing the pharyngeal airway) and in patients in whom continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is inadequate (Epstein EJ, Evidence Based Clinical Guideline).

Surgical treatment of pediatric sleep-disordered breathing with tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy is the recommended first-line treatment. In the pediatric population, resolution of OSA occurs in 82 percent of patients who are treated with tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (Breitzke, S, Meta-analysis). Another recent publication of specific interest for otolaryngologists is a large multicenter retrospective review on the treatment outcomes for OSA after an adenotonsillectomy. This review included 578 children of which 90 percent of the children were younger than 13 years of age. Fifty percent of the children were obese (BMI > 95 percent). Only 27 percent of the children had complete resolution of OSA (AHI < 1 total sleep time) while 21.6 percent had an AHI>5/hr TST. Surgical success was variable and depended upon outcome measures selected. So success is as low as 27 percent (AHI of < 1) or as high as 78 percent (AHI <5). Fifty nine percent of the obese children had an AHI>5/hr TST. An analysis of factors that were associated with an elevated post-operative AHI in order of influence were older than seven years, elevated BMI, presence of asthma, and more severe OSA pre-operatively.

In most patients with moderate to severe OSA, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first line treatment. Successful long-term treatment of OSA with CPAP is difficult to achieve and fewer than 50 percent of patients on CPAP are adequately treated, as defined by four hours of use 70 percent of nights (Weaver, TE, Level 2 evidence and Kribbs, NB, Level 2 evidence). Other treatment options must be available to patients with OSAS.

Surgical procedures may be considered as a secondary treatment for OSA when the outcome of PAP therapy is inadequate, such as when the patient is intolerant of CPAP, or CPAP therapy is unable to eliminate OSA (Consensus). Surgery may also be considered as a secondary therapy when there is an inadequate treatment outcome with an oral appliance (OA), when the patient is intolerant of the OA, or the OA therapy provides unacceptable improvement of clinical outcomes of OSA (Consensus). Surgery may also be considered as an adjunct therapy when obstructive anatomy or functional deficiencies compromise other therapies or to improve tolerance of other OSA treatments (Consensus)(Epstein, EJ). Surgery for OSAS has been shown to improve important clinical outcomes including survival and quality of life (Weaver, EM. Level 2 evidence).

References

- Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, Mitchell RB, Promchiarak J, Simakajornboon N, Kaditis AG, Splaingard D, Splaingard M, Brooks LJ, Marcus CL, Sin S, Arens R, Verhulst SL, Gozal D. Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Sep 1;182(5):676-83. Epub 2010 May 6. PubMed PMID: 20448096.

- Epstein, EJ (Chair), Kristo, D, Strollo, Jr. PJ. Clinical Guidelines for the Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 5(3):263-79, 2009.

- Brietzke S, Gallagher D. The effectiveness of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: A meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134(6), 979-984, 2006.

- Weaver TE, Grunstein RR; Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 5(2):173-8, 2008.

- Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 147:887-95.1993.

- Weaver EM, Maynard C, Yueh B. Survival of veterans with sleep apnea: continuous positive airway pressure versus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 130(6):659-65. 2004.

Cochlear Implants and Meningitis Vaccination—UPDATED

What you should know

- Children with cochlear implants are more likely to get bacterial meningitis than children without cochlear implants. In addition, some children who are candidates for cochlear implants have inner ear anatomic abnormalities that may increase their risk for meningitis.

- Because children with cochlear implants are at increased risk for pneumococcal meningitis, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that they receive pneumococcal vaccination on the same schedule that is recommended for other groups at increased risk for invasive pneumococcal disease. Recommendations for the timing and type of pneumococcal vaccination vary with age and vaccination history and should be discussed with a healthcare provider.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for individuals with cochlear implants. These recommendations can be viewed in detail on the CDC website: (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5909a2.htm).

- Children who have cochlear implants or are candidates for cochlear implants should receive PCV13. PCV13 is now recommended routinely for all infants and children (see Table 2 in the CDC March 12, 2010 MMWR issue located at the above website for the number of doses and dosing schedule).

- Older children with cochlear implants (from age two years through age five) should receive two doses of PCV13 if they have not received any doses of PCV7 or PCV13 previously. If they have already completed the four-dose PCV7 series, they should receive one dose of PCV13 through age 71 months.

- Children six through 18 years of age with cochlear implants may receive a single dose of PCV13 regardless of whether they have previously received PCV7 or the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) (Pneumovax®).

- In addition to receiving PCV13, children with cochlear implants should receive one dose of PPSV23 at age two years or older and after completing all recommended doses of PCV13.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for adults with cochlear implants. These recommendations can be viewed in detail on the CDC website: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6140a4.htm.

- Adult patients (=19 yrs of age) who are candidates for a cochlear implant and those who have received a cochlear implant should be given a single dose of PCV13 followed by a PPSV23 at least eight weeks later. A second dose of PPSV23 is recommended for those 65 years old and older.

- For those adults who previously have received =1 doses of PPSV23 should be given a PCV13 dose =1 year after the last PPSV23 dose was received. For those who require additional doses of PPSV23, the first such dose should be given no sooner than eight weeks after PCV13 and at least five years after the most recent dose of PPSV23.

- For both children and adults, the vaccination schedule should be completed at two weeks or more before surgery.

Additional Facts

- According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as of April 2009, approximately 188,000 people worldwide have received cochlear implants. In the United States, roughly 41,500 adults and 25,500 children have received them. In the U.S., there are 122 known reports of meningitis in patients who have received cochlear implants with 64 percent of these cases having occurred in children.

- Meningitis is an infection of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. There are two main types of meningitis, viral and bacterial. Bacterial meningitis is the more serious type and the type that has been reported in individuals with cochlear implants. The symptoms, treatment, and outcomes may differ depending on the cause of the meningitis.

- The vaccines available in the United States that protect against most bacteria that cause meningitis are:

- 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) (Prevnar 13®)

- 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV) (Pneumovax®)

- Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate (Hib)

- Tetravalent (A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal conjugate (Menactra® and Menveo®)

- Tetravalent (A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal polysaccharide (Menomune®)

- Meningitis in individuals with cochlear implants is most commonly caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus). Children with cochlear implants are more likely to get pneumococcal meningitis than children without cochlear implants.

- There is no evidence that children with cochlear implants are more likely to get meningococcal meningitis, caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitides, than children without cochlear implants. Healthcare providers should follow the CDC immunization guidelines for routine meningococcal vaccination.

- The Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine is not routinely recommended for those five years old or older, since most older children and adults are already immune to Hib. Available information does not suggest that older children and adults with cochlear implants require the Hib vaccine. However, the Hib vaccine can be given to older children and adults who have never received it. Children younger than age five should receive the Hib vaccine as a routine protection, according to the CDC guidelines for childhood immunizations. Most children born after 1990 have received the Hib vaccine as infants.

- Healthcare providers (family physicians, pediatricians, and otolaryngologists) and families should review the vaccination records of current and prospective cochlear implant recipients to ensure that all recommended vaccinations are up to date

After beginning in the Fall of 2012 with a review of those policies which were the most out of date and most highly utilized first, we have progressed to the second round of review. In 2013, the Academy will be continuing to request Academy Committees’ assistance for second and third round reviews to ensure that the policy content is up to date. If you have any questions regarding the policy statement update process, please email healthpolicy@entnet.org.

The Physician Payment Policy Workgroup (3P)

The Airway and Swallowing Committee

The Equilibrium Committee

The Head and Neck Surgery Education Committee

The Hearing Committee

The Imaging Committee

The Implantable Hearing Devices Committee

The Medical Devices and Drugs Committee

The Pediatric Otolaryngology Committee

The Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Committee

The Rhinology and Paranasal Sinus Committee

The Sleep Disorders Committee

The Voice Committee