The Milan System for Salivary Gland Cytopathology

This system to standardize and improve reporting of fine needle aspiration findings can help guide clinicians and patients when discussing the necessity, urgency, and extent of surgery and prognosis with an identified parotid gland lesion.

Jeffrey C. Mecham, MD, Ameya A. Asarkar, MD, and Brent A. Chang, MD, on behalf of the Head and Neck Surgery & Oncology Committee

In this setting, a 2015 international workgroup of 47 experts in the diagnosis and management of salivary gland pathology was organized in Milan, Italy, to devise a system to standardize and improve reporting of FNA findings for salivary gland lesions. This system was named the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC).4,5

What Is the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology?

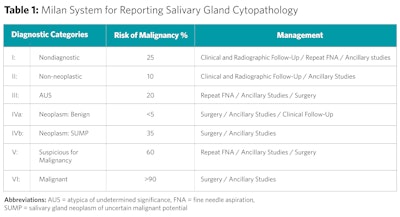

Similar to the Bethesda system for thyroid lesions, the MSRSGC includes a tiered categorical framework for reporting FNA findings of salivary gland lesions. FNAs are categorized into one of six categories: 1) nondiagnostic, 2) nonneoplastic, 3) atypia of undetermined significance (AUS), 4) neoplasm (subdivided into [a] benign neoplasms and [b] salivary gland neoplasms of uncertain malignant potential [SUMPs]), 5) suspicious for malignancy, and 6) malignant. Each category is ascribed an implied risk of malignancy (ROM) and a brief management strategy (Table 1).

What Is the Evidence Supporting It?

Since its inception, many studies have validated the use of the Milan system, particularly in determining neoplastic process versus non-neoplastic process and benign neoplasm versus malignant neoplasm.

Jalaly et al. performed a comprehensive review of 37 published studies validating the MSRSGC, including a total of over 16,000 salivary gland FNAs with over 8,000 histopathologic follow ups. In this, the mean false positive rate for categories V (suspicious for malignancy) and VI (malignant) was 5.1%. The mean false negative rate for category II (non-neoplastic) and category IVa (neoplasm-benign) was 4.5%. The pooled sensitivity and specificity for detecting neoplasm were 97.2% and 88.2%, respectively. The pooled sensitivity and specificity for detecting malignancy were 84.7% and 99.5%. This study also validated that in this large sample, the pooled ROM for each category fell mostly within the recommended ranges published within the MSRSGC.6

The utility of the MSRSGC has been validated both in parotid gland and submandibular gland pathology.7-9 Its utility in submandibular pathology is important given that while the relative occurrence of lesions in the submandibular gland is much less than the parotid gland, the likelihood of malignancy in a submandibular gland lesion is much higher than the parotid.9

Why Is It Potentially Useful?

The MSRSGC emphasizes the importance of risk of malignancy over determining the specific diagnosis. From a practical clinical perspective, this can guide clinicians and patients when discussing the necessity, urgency, and extent of surgery and prognosis when discussing potential management strategies of an identified parotid gland lesion.10

In one example of its implementation, a Dutch study demonstrated prioritization of time to treatment initiation for higher category Milan categories.7 This becomes especially important in resource-limited settings.

Additionally, the Milan system may help in patient discussions weighing the benefits and risks of proceeding to surgery when a patient has additional comorbidities that increase the risk of perioperative complications. Having a standardized classification system has significant potential benefits for patient counselling and preoperative decision making.

What Are the Potential Limitations of Its Use?

FNA relies on the skill and experience of both the individual performing the FNA and the cytopathologist interpreting the biopsy. Therefore, the utility of FNA likely favors institutions with higher volume of salivary gland lesions. This is demonstrated in one study where the sensitivity of FNA using the Milan system was higher in specialized oncologic centers compared with general hospitals.8

Cystic salivary gland lesions also pose a challenge owing to the higher likelihood of nondiagnostic samples due to inadequate cellularity of the aspirate. For this reason, it is advised to perform a post-evacuation FNA with multiple passes for cystic salivary lesions to reduce the likelihood of a false negative result.11

While one goal of creating a standardized framework is to eliminate inter-observer bias, bias itself cannot be entirely eliminated. Studies suggest the greatest interrater reliability for more definitive categories (nondiagnostic, non-neoplastic, neoplasm-benign, and malignant) and the least interrater reliability in the less definitive categories (atypia of unknown significance, salivary lesions of uncertain malignant potential, and suspicious for malignancy).5,6 Special care should therefore be considered when counseling patients with FNA in the latter of these categories.

How Can the System Be Implemented?

The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that pathologists report risk of malignancy for salivary gland FNA using a risk stratification scheme.12 Despite this, use of the MSRSGC has been adopted with varying consistency—unlike the Bethesda system, which has a more universal adoption.

One multicenter study looking retrospectively at FNAs of salivary gland lesions between the period of 2018 to 2021 demonstrated categorization of FNA findings using the MSRSGC in only 6.4% of 10,064 cases. Interestingly, at one of the three sites in this study, institutional emphasis on its use increased the percentage of cases reported with Milan classification up to 24.2%.7 Although it is difficult to extrapolate from this single study, this does demonstrate:

- The MSRSGC is likely underutilized despite the multitudes of evidence supporting its use.

- Institutional and multidisciplinary emphasis can increase its use.

As the system was devised to facilitate interdisciplinary communication, proper implementation of the MSRSGC requires a consensus within the care team of patients for salivary gland lesions. A close collaboration between the surgical and pathology teams is critical.

References

- Vasconcelos AC, Nor F, Meurer L, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of salivary gland tumors over a 15-year period. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30doi:10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0002

- Cibas ES DB. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

- Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Sep 2010;68(9):2146-53. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.064

- Faquin WC RE, Baloch ZW, Field A, Katabi N, Wenig BM. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Springer; 2018:chap 1-9.

- Rossi ED, Faquin WC. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC): An international effort toward improved patient care-when the roots might be inspired by Leonardo da Vinci. Cancer Cytopathol. Sep 2018;126(9):756-766. doi:10.1002/cncy.22040

- Jalaly JB, Farahani SJ, Baloch ZW. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A comprehensive review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. Oct 2020;48(10):880-889. doi:10.1002/dc.24536

- Reerds STH, Honings J, van Engen ACH, Marres HAM, Takes RP, van den Hoogen FJA. Prioritizing parotid gland surgery: A call for the implementation of the MSRSGC classification. Cancer Cytopathol. Nov 2023;131(11):701-707. doi:10.1002/cncy.22747

- Reerds STH, van Engen-van Grunsven ACH, van den Hoogen FJA, Takes RP, Marres HAM, Honings J. Validation of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology and the diagnostic accuracy of FNA cytology for submandibular gland lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. Mar 2022;130(3):189-194. doi:10.1002/cncy.22532

- Maleki Z, Baloch Z, Lu R, et al. Application of the Milan System for Reporting Submandibular Gland Cytopathology: An international, multi-institutional study. Cancer Cytopathol. May 2019;127(5):306-315. doi:10.1002/cncy.22135

- Hosseini SM, Resta IT, Baloch ZW. Diagnostic performance of Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A prospective study. Diagn Cytopathol. Jul 2021;49(7):822-831. doi:10.1002/dc.24748

- Singh G, Jahan A, Yadav SK, Gupta R, Sarin N, Singh S. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: An outcome of retrospective application to three years’ cytology data of a tertiary care hospital. Cytojournal. 2021;18:12. doi:10.25259/Cytojournal_1_2021

- Geiger JL, Ismaila N, Beadle B, et al. Management of Salivary Gland Malignancy: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. Jun 10 2021;39(17):1909-1941. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.00449