Climate Health and Pediatric Otolaryngology

Adverse health impacts resulting from climate change affect certain vulnerable groups to a greater extent than others. This includes children.

Kara D. Meister, MD, Chair, Pediatric Otolaryngology Education Committee

The adverse health impacts resulting from climate change and climate-related emergencies affect certain vulnerable groups to a greater extent, notably people of color, individuals with lower income, those with preexisting health conditions, older adults, and children. Climate change is influencing the health of children in the United States. In the infant population, climate-related hazards such as extreme heat, flooding, and wildfires have been linked to maternal complications of pregnancy such as anemia, preeclampsia, preterm birth, and miscarriage.1

In November 2023, a Call for Action was released by United Nations (UN) agencies advocating for countries to plan for the effects of catastrophic climate events. Children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable to the health effects of climate change specifically as it relates to global warming and the subsequent increase of infectious diseases such as cholera, malaria, and dengue fever, and the threats to food security.

Apropos to pediatric otolaryngology, there are conditions we treat commonly that are likely influenced by climate health including allergic rhinitis,2 sleep disordered breathing,3 and complications of infectious diseases such as nontuberculous mycobacterial infections of the head and neck.4 The importance of the otolaryngology community to continue educating ourselves, our institutions and colleagues, and our patients about climate change and health was nicely summarized in a recent commentary by Haugen, et al.5

As healthcare practitioners, we should also be aware of the impact of U.S. healthcare on the environment. According to the Commonwealth Fund, the U.S. healthcare sector is responsible for 8.5% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.6 The primary contributors to carbon emissions within the health system are hospital care, accounting for 36%, followed by physician and clinical services at 12%, and prescription drugs at 10%.6

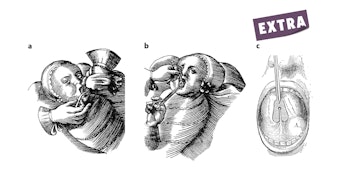

At my institution, Stanford University, M. Lauren Lalakea, MD, has been leading the effort to reduce waste and promote sustainability within our department as well as at one of the affiliate hospital systems. Through her advocacy, we have begun a repurchasing program for single-use devices and have launched a trial of certain reprocessed devices among other initiatives. Specifically in the domain of pediatric otolaryngology, there are ongoing efforts to streamline the surgical instruments and disposables used for the most performed procedures, and to question our own practices of pharmaceuticals being opened, dispensed, and prescribed. One example is changing the practice pattern of routinely prescribing perioperative ear drops in children undergoing tympanostomy tube placement to reflect the AAO-HNSF Clinical Practice Guideline Tympanostomy Tubes in Children (Update), which recommend against such use—not only is it best practice, but it is potentially better for the carbon footprint as well.7

During Kids ENT Health Month, I’m excited to engage in mutual learning, exploring the most effective ways to research, advocate, and champion environmental justice. Together with our patients, we can better understand the potential effects of climate change on child and maternal health, and advocate for innovative solutions to decrease our own carbon footprint.

References

- US EPA O. Climate Change and the Health of Pregnant, Breastfeeding, and Postpartum Women. Published March 21, 2022. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-and-health-pregnant-breastfeeding-and-postpartum-women

- Ziska LH. An Overview of Rising CO 2 and Climatic Change on Aeroallergens and Allergic Diseases. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12(5):771. doi:10.4168/aair.2020.12.5.771

- Lo CC, Liu WT, Lu YH, et al. Air pollution associated with cognitive decline by the mediating effects of sleep cycle disruption and changes in brain structure in adults. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(35):52355-52366. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19482-7

- Kambali S, Quinonez E, Sharifi A, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in Florida and association with large-scale natural disasters. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2058. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12115-7

- Haugen T, Prichardo P, Hellums R, Lindemann L. Climate Change and Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2023;168(5):1261-1263. doi:10.1002/ohn.189

- How the U.S. Health Care System Contributes to Climate Change. doi:10.26099/m2nn-gh13

- Rosenfeld RM, Tunkel DE, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Tympanostomy Tubes in Children (Update). Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2022;166(S1). doi:10.1177/01945998211065662