For Your Patients: Acute Complications of Common Pediatric Otolaryngologic Diseases

Risk factors that may predispose certain children to complicated infections and the signs that should prompt parents to obtain more urgent evaluation.

Jason R. Brown, DO, John P. Dahl, MD, Philip D. Knollman, MD, Lilun Li, MD, and James M. Ruda, MD, Pediatric Otolaryngology Committee

Common winter illnesses include ear infections, sinus infections, and neck infections. Ear infections are common in children, with an estimate of 40% of children having three or more ear infections by the age of six.3 Acute sinus infections are present in approximately 6%–7% of children with respiratory symptoms, with a small percentage caused by bacteria.1 The lymph nodes commonly enlarge during upper respiratory infections to mount immune responses to the infection. Often these infections can be diagnosed and treated by your child’s pediatrician with a course of antibiotics.

However, there has been a rise in complications from these illnesses over the past year after the lifting of COVID pandemic restrictions, likely due to decreased individual and herd immunity.1,2,4 The most common complication of ear infections is of the surrounding bone (called mastoiditis), and the most common complication of sinus infections is of the neighboring eye (orbital cellulitis). Both infections can also spread to areas surrounding or within the brain. Enlarged neck lymph nodes can progress to collections of pus within the lymph node or the surrounding areas (a pocket of pus like this is called an “abscess”).

While some of these complications can be managed by hospital admission and intravenous antibiotics, a rising number are requiring imaging studies and surgical intervention.2 This article aims to summarize the various complications of ear, sinus, and neck infections, identify risk factors that may predispose certain children to complicated infections, and highlight the signs that should prompt parents to obtain more urgent evaluation.

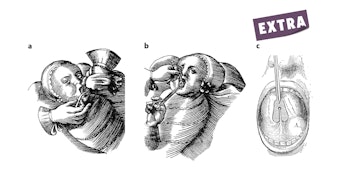

Acute Otitis Media and Its Complications

AOM is frequently diagnosed with signs of an earache or a sense of fullness in the ear(s), fever (100.4°–104°), rubbing the ears, crying or irritability, poor feeding, trouble sleeping, restlessness, decreased hearing, and symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection.7,8 Treatment of milder cases of AOM can involve both time (that is, waiting for symptoms to resolve) and supportive treatment with pain relief medications and anti-fever medications for 24–48 hours. However, if the initial symptoms of AOM are severe, fail to improve, or worsen over 24–48 hours, parents should seek a medical evaluation.9 Factors such as the child’s age, presence and severity of fever, and involvement of one/both ears will help your clinician determine whether antibiotic therapy is required.8

In most children, AOM often resolves with time and without a need for antibiotics. When antibiotics are started, ear symptoms such as fever, ear pain, or irritability often begin to improve within three days. If not, antibiotics may need to be adjusted. However, occasionally, children can develop new or recurrent ear infection(s) within a short time after completing the antibiotic course prescribed for the original infection.5 Recurrent AOM is often defined as three ear infections in six months or four ear infections occurring within 12 months.10 If ear symptoms do not improve with antibiotics or there is concern for a new ear infection, parents should seek an additional re-evaluation by a medical professional.

Failure to treat AOM can result in chronic middle ear fluid, conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, new facial nerve weakness, tympanic membrane (eardrum) perforation, drainage from the ear, and the spread of infection into the mastoid (the large bone behind the ear). The spread of infection can occur by direct extension within the bone around the ear, through infection and clotting of the blood vessels around the ear, or spread within the blood. Within the skull, such infection can involve the inner ear, and can cause meningitis, brain abscess, and clotting of veins around the brain, which can contribute to symptoms of headache, dizziness, fever, marked changes in a child’s behavior, and drowsiness. In children, the most common complication outside the brain and skull is an abscess behind the ear, which presents as swelling or fullness, redness, and pain behind the ear. If these symptoms occur, parents must take their child to the emergency room for evaluation. The most common complication from an AOM within the skull is meningitis or infection of the membranes surrounding the brain. When acute complications of AOM occur, the most common early symptoms are persistent headache and fever. Progressive worsening of these symptoms causes lethargy (excessive tiredness), nausea and vomiting, mental status change, and foul-smelling drainage from the ear.11-12

If a child’s AOM symptoms worsen despite being on antibiotics, they should be taken back to their pediatrician or to the emergency department for further evaluation. If the ear exam shows a red, dull, or bulging ear drum, and the child has an ongoing high fever, headache, severe ear pain, change in their behavior or thinking, or lethargy, then the healthcare professional will perform additional evaluations. This can involve obtaining bloodwork to look for evidence of infection as well as CT imaging of the bone around the ear, or even an MRI of the brain. These scans will check to see whether the ear infection has spread to the mastoid bone and for any involvement of the brain or clotting of the blood vessels around the brain. If so, surgery to address the ear infection and its complications may be required. Such surgery could involve placing ear tubes within the ear drum(s), drilling out the mastoid bone behind the ear, and draining any abscesses behind the ear or around the brain. Occasionally, the latter may require surgical assistance from other specialists such as ophthalmologists or neurosurgeons. If a complication from AOM goes unrecognized, the consequences could result in long-term physical and mental impairment, or even be fatal, despite the original infection being treated medically or surgically. Even with prompt detection and surgery to clear the infection, a prolonged hospital stay may be required until the infection has been fully treated and an optimal antibiotic regimen finalized.

While it is impossible to predict which children will develop complications from AOM, there are some general strategies that parents can use to help reduce the risk of AOM and its complications. It is very important for children to be up to date on their routine vaccinations including the pneumococcal vaccine that helps protect against some strains of Streptococcus, a common bacteria that causes AOM. Minimizing tobacco smoke exposure while around your child and minimizing your child’s exposure to other sick children can help decrease the likelihood of your child getting sick with a viral illness and developing an ear infection. Finally, if the symptoms of a child’s ear infection are worsening despite watchful waiting or antibiotic treatment, it is important to seek medical attention to recheck the status of the ear infection. Going to an urgent care facility or the emergency room may be necessary if the symptoms from a child’s ear infection are not improving, or other more serious symptoms begin to develop (as described above).

Neck Masses and Their Complications

The most common lesion in the neck in children is enlarged lymph nodes. It is estimated that more than 90% of kids will experience this in their childhood. When infected, these lymph nodes can grow, causing discomfort, fever, and reduced neck mobility. Sometimes a pus pocket, or abscess, will form in the center of the lymph node and may require a surgical procedure as a part of treatment. However, many small abscesses can be treated with oral antibiotics alone. The most common cause of enlarged lymph nodes in the neck is a viral upper respiratory infection and can be treated with conservative measures like nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen) and proper hydration. However, when neck lymph nodes are infected with bacteria, the most common culprits are Streptococcal and Staphylococcal species that may require antibiotics to treat. If there is fever, pain, or redness, this may indicate that bacteria have caused a pus pocket or abscess to form and may require drainage. If your medical professional suspects this, they may request imaging in the form of an ultrasound or computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. Your healthcare team will decide if a surgical procedure is necessary based on your child’s history, physical exam findings, and the results of imaging. If surgery is necessary, it is usually performed by either a general surgeon or otolaryngologist in the hospital. Kids may be at higher risk of developing enlarged lymph nodes with or without abscess formation if they have underlying medical conditions such as an immune deficiency, a pre-existing congenital neck mass or malformation, or if they have been recently diagnosed or treated for other diseases that lower the response of the immune system.13

While infection is by far the most common cause of neck masses in kids, it is important to remember that not all neck masses in kids are due to infection. The second most common neck lesions are congenital neck masses (that is, masses that appear at birth) and can often be treated in an outpatient setting. These can include thyroglossal duct cysts (a lump in the front part of the neck) and dermoid cysts (a saclike growth that can continue skin or hair), which do not cause pain or discomfort when not infected. Such cysts form in the middle of the front part of the neck. Other congenital neck lesions include branchial cleft cysts or sinuses and may present with a small (sometimes mucus-draining) pit next to the long muscle in the neck called the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Occasionally these congenital neck masses can become infected and necessitate the use of antibiotics to treat the acute infection. If your primary care physician suspects a congenital neck mass, your child may be referred to a surgical specialist for definitive treatment. Your surgical specialist may request an ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to better characterize the lesion and plan for surgery.

Most of the time, neck masses are not concerning for cancer, but there can be some clues that may make your physician worry. An enlarging neck mass without overlying skin changes in a patient with fevers, chills, soaking night sweats, weight loss, and loss of appetite may be indicative of lymphoma. It is important to remember that while lymphoma is the most common cancer in children overall, it is rare and occurs in only about 5–15 individuals per one million kids.14

In summary, most neck masses are infectious and benign (noncancerous) and only require conservative treatment. Neck masses lasting over two weeks need to be evaluated by a medical professional. There may be findings that could prompt further testing such as lab studies or imaging. Definitive treatment may require surgery. If in doubt about any lumps or bumps in your child’s neck, make an appointment to see your medical professional.

Acute Sinusitis and Its Complications

When symptoms persist without improvement for longer than 7–10 days, or worsen over that time, then the sinus infection may be caused by bacteria. Bacterial sinusitis occurs in only about 5%–10% of all upper respiratory infections. Although a bacterial sinus infection may still resolve on its own, treatment with antibiotics may help promote recovery from the infection more quickly. Of course, it is important that your pediatrician help distinguish between viral sinusitis and bacterial sinusitis to prevent the overuse of antibiotics when they are not needed. If your child experiences persistent symptoms without improvement, has signs of a high fever (>102°F) that lasts for more than three days, or seems generally ill, please see a pediatrician to determine whether an antibiotic is appropriate.15

Children with untreated bacterial sinusitis are at risk of developing complications from the infection, typically associated with the spread of inflammation and infection beyond the sinuses themselves. The rate at which these complications occur is generally quite low (< 5% of all cases of bacterial sinusitis); however, there are important signs and symptoms to keep in mind. If your child develops the signs and symptoms associated with a complication of a sinus infection, then urgent evaluation is needed.16

When a sinus infections spreads toward the structures around the eye (orbital complication), then your child may present with swelling and redness of the eyelid or skin around the eyes, swelling and redness of the eye itself, pain with eye movement, limitations in eye movement, or change in vision. As these symptoms may indicate a severe infection (for example, periorbital cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, or abscess), your child should be evaluated in the emergency room. An ophthalmologist and an otolaryngologist will likely be asked to help evaluate your child as well. Your healthcare team will usually carry out imaging (such as a CT scan) and lab work to evaluate the severity of the infection and determine the correct treatment. In many such cases, the patient will need to be admitted to the hospital to receive antibiotics through an IV. In some cases, a clinician may need to surgically drain the infection in the operating room.

In rare cases, an infection may spread beyond the sinuses toward the compartment that houses the brain (intracranial complication). An intracranial infection can affect the bone and soft tissues around the forehead sinuses in a condition known as Pott’s puffy tumor, leading to swelling and pain around the forehead or scalp. An infection can also affect the protective layers around the brain or the brain itself (meningitis or intracranial abscess). Symptoms include headache, vomiting, a change in level of consciousness or mental status, neurological deficits such as changes in movement or sensation, neck stiffness, and seizures. These symptoms certainly warrant urgent evaluation in the emergency room. An otolaryngologist and a neurosurgeon will likely help in the evaluation. Lab work and imaging with a CT scan and MRI will be obtained. Additional procedures, such as a lumbar puncture, may be necessary as well. Many cases will require a combination of IV antibiotics and surgical drainage of the infection, as these infections can be very serious and cause long-term disability.17

If your child has a history of uncomplicated sinusitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics, frequent recurrent sinus infections requiring antibiotics, symptoms of sinusitis that last for more than three months without improvement despite treatment, or prior complications of a sinus infection (such as orbital or intracranial complications of sinusitis), please consider taking them to see an otolaryngologist in clinic to discuss options for treatment.

References

- Kalavacherla, Sandhya, Madelyn Hall, Wen Jiang, and Daniela Carvalho. "Temporal Trends in Pediatric Acute Sinusitis Surrounding the COVID‐19 Pandemic." Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (2023). doi:10.1002/ohn.578

- Metz, Corona, Andrea Schmid, and Simon Veldhoen. "Increase in complicated upper respiratory tract infection in children during the 2022/2023 winter season—a post coronavirus disease 2019 effect?." Pediatric Radiology 54, no. 1 (2024): 49-57. doi:10.1007/s00247-023-05808-1

- Rosenfeld, Richard M., David E. Tunkel, Seth R. Schwartz, Samantha Anne, Charles E. Bishop, Daniel C. Chelius, Jesse Hackell et al. "Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children (update)." Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 166 (2022): S1-S55. doi:10.1177/01945998211065662

- Voß, Noemi, Nadia Sadok, Sarah Goretzki, Christian Dohna-Schwake, Moritz F. Meyer, Stefan Mattheis, Stephan Lang, and Kerstin Stähr. "Häufung von Komplikationen der akuten Otitis media und Sinusitis bei Kindern 2022/2023." HNO (2023): 1-7. doi:10.1007/s00106-023-01393-9

- Sakulchit, Teeranai, and Ran D. Goldman. "Antibiotic therapy for children with acute otitis media." Canadian Family Physician 63, no. 9 (2017): 685-687.

- Kaur Ravinder, Morris Matthew, Pichichero Michael E., Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatrics. 2017; 140 (3): e20170181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0181

- Daly, Kathleen A., Howard J. Hoffman, Kari Jorunn Kvaerner, Ellen Kvestad, Margaretha L. Casselbrant, Preben Homoe, and Maroeska M. Rovers. "Epidemiology, natural history, and risk factors: panel report from the Ninth International Research Conference on Otitis Media." International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 74, no. 3 (2010): 231-240.

- Lieberthal, Allan S., Aaron E. Carroll, Tasnee Chonmaitree, Theodore G. Ganiats, Alejandro Hoberman, Mary Anne Jackson, Mark D. Joffe et al. "The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media." Pediatrics 131, no. 3 (2013): e964-e999. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3488

- Smolinski, Nicole E., Patrick J. Antonelli, and Almut G. Winterstein. "Watchful waiting for acute otitis media." Pediatrics 150, no. 1 (2022): e2021055613.

- Granath, Anna. "Recurrent acute otitis media: what are the options for treatment and prevention?." Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports 5 (2017): 93-100. doi: 10.1007/s40136-017-0151-7

- Mattos, Jose L., Kathryn L. Colman, Margaretha L. Casselbrant, and David H. Chi. "Intratemporal and intracranial complications of acute otitis media in a pediatric population." International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 78, no. 12 (2014): 2161-2164.

- Ren, Yin, Rosh KV Sethi, and Konstantina M. Stankovic. "Acute otitis media and associated complications in United States emergency departments." Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 39, no. 8 (2018): 1005. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001929

- Meier, Jeremy D., and Johannes Fredrik Grimmer. "Evaluation and management of neck masses in children." American family physician 89, no. 5 (2014): 353-358.

- Minard-Colin, Véronique, Laurence Brugières, Alfred Reiter, Mitchell S. Cairo, Thomas G. Gross, Wilhelm Woessmann, Birgit Burkhardt et al. "Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents: progress through effective collaboration, current knowledge, and challenges ahead." Journal of Clinical Oncology 33, no. 27 (2015): 2963.

- Chow, Anthony W., Michael S. Benninger, Itzhak Brook, Jan L. Brozek, Ellie JC Goldstein, Lauri A. Hicks, George A. Pankey et al. "IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults." Clinical infectious diseases 54, no. 8 (2012): e72-e112.

- Wald, Ellen R., Kimberly E. Applegate, Clay Bordley, David H. Darrow, Mary P. Glode, S. Michael Marcy, Carrie E. Nelson et al. "Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years." Pediatrics 132, no. 1 (2013): e262-e280.

- Thomas, Mike, Barbara Yawn, David Price, Valerie Lund, Jocquim Mullol, and Wytske Fokkens. "EPOS primary care guidelines: European position paper on the primary care diagnosis and management of rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007—a summary." Primary Care Respiratory Journal 17, no. 2 (2008): 79-89.