Déjà Vu All Over Again

Scope-of-practice issues continue to arise, and we must be vigilant in weighing in on them.

James C. Denneny III, MD

James C. Denneny III, MD

AAO-HNS/F Executive Vice President and CEO

New technology and medical advances add another wrinkle to the equation since a large percentage of trainees in a specialty area have not had specific experience with a new device but are intimately familiar with the anatomic area and physiology related to the clinical advance. Medical and surgical specialists have access to state-of-the-art continuing education offered year-round and practice a lifelong learning ethos that affords the opportunity to be familiar with and facile in new treatment modalities.

Nonphysician groups are constantly looking to expand their scope of practice into traditional physician areas, often cloaked in the promise of improved patient access. Federal government concessions that relaxed standards during the COVID-19 pandemic to foster access to care through telehealth and other non-face-to-face options served to accelerate scope expansion attempts and, in some cases, reduced oversight of privileges at the federal and state levels. Unlike scope issues in the physician arena, which can usually be negotiated with subsequent co-existence, the nonphysician groups continually ask for greater privileges with each expansion.

One of my most memorable scope-of-practice interactions started with a new provost’s (a speech pathologist) unilateral decision to remove audiology from the department of otorhinolaryngology, which led to closure of the department three months before I was supposed to start my residency.

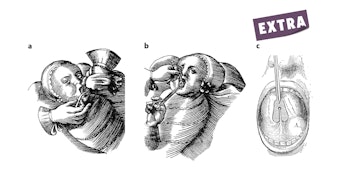

Following completion of my residency at an alternative site, I completed a fellowship in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery and was thrust into the ongoing scope-of-practice and recognition battle with plastic surgeons that culminated with Jack R. Anderson, MD, and his successful lawsuit that established the validity of otolaryngology-trained facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons in 1987.

After leaving academic medicine and starting my first private practice in Knoxville, Tennessee, I was denied the right to do thyroid surgery by the medical director (a general surgeon) of a prominent private payer in the region, even though I had hospital privileges for the requested case in question.

More recently, thyroid surgery came up again when the American Board of Surgery and the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons put forth a stealth proposal to enact a Practice Focus Designation favoring fellowship-trained general surgeons.

Otolaryngology and hearing healthcare have been in the crosshairs of the audiology community continuously over the last 25 years at the state and federal legislative levels as well as federal and state regulatory agencies.

Despite my expectation that 2024 would undoubtedly be another busy year in dealing with scope-of-practice issues that we routinely address, as well as some that we were not expecting, I was surprised to hear from the otolaryngology community in Australia in late 2023 about an issue they were having with the aesthetic surgeons in their country that was reminiscent of the same struggles I witnessed early in my career 40+ years ago.

The Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (ASAPS) filed a complaint with Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency's (Ahpra) Medical Board questioning the suitability of otolaryngology-trained surgeons to be designated “Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons” that is currently under review. After discussing the matter with leadership of the Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery Ltd, it became clear that this is a critical issue to the global otolaryngology community and that it was incumbent on the Academy to weigh in on the issue. In deciding how to put the most effective presentation together, I felt it is important to highlight the same strategies that we employ in other scope-of-practice and advocacy activities.

A critical point in coming to a decision that is both correct and defensible lies in the definition of the category “plastic surgeon” as listed in the statute. In this instance, we referenced a dictionary definition as well as quotations from several websites including the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the American Board of Cosmetic (Aesthetic) Surgery, and the American College of Surgeons.

This compilation of definitions indicates that the majority of the medical community considers “plastic surgery” to include both reconstructive and cosmetic or aesthetic procedures to be within the scope of practice for plastic surgeons.” Interestingly enough, the group filing the complaint against otolaryngology-trained facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons, ASAPS, would not qualify for status under the statute descriptor “plastic surgery” whereas, otolaryngology-trained facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons would.

Defining the specialty or service involved is important, but it is equally important to identify who is qualified to call themselves a “plastic surgeon” (in this case), but it could be physician or whatever designation fits the issue involved. This requires delineation of training including the length and breadth that meet the minimum standard, verification of competence through a comprehensive certification program, and demonstrating that same competence and skill through treating patients in real-world situations.

The same principles should be used as a model for driving our advocacy efforts, whatever the area of concern, both now and in the future.