Survey: Employee Contract Non-Compete Clauses

The Private Practice Study Group (PPSG) asked its members about the value of non-compete clauses in the face of a potential FTC ban on them.

Marc G. Dubin, MD (PPSG Chair), David E. Melon (PPSG Vice-Chair), Daniel R. Gold, MD, Annette M. Pham, MD, and Melanie W. Seybt, MD (PSSG Executive Committee)

WATCH: James C. Denneny III, MD, AAO-HNS/F Executive Vice President and CEO, as well as Editor of the Bulletin, provide introductory remarks to this article written by the Private Practice Study Group (PPSG) regarding a survey conducted on the topic of Employee Contract Non-Compete Clauses.

In early January 2023, the Federal Trade Commission issued a plan to ban non-compete clauses, a common employment contract covenant for many employees, physicians included. Now in the 60-day comment period, the final ruling is certain to be the subject of numerous lawsuits with one already considered by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The result has the potential to dramatically affect the house of medicine with this federal ruling superseding any less stringent state regulations and policies.

At minimum, any change in the status quo will affect physicians who often have roles as both employer and employee. As such, they may have non-compete clauses in their own contracts and may be simultaneously using them as a protective mechanism when hiring and investing in employees. While seen by the federal government as a limitation on an individual's rights, as an employer and participating party in a partnership, there is the potential for considerable economic damage if an employee/partner leaves to practice independently and in competition. Non-competes in this setting protect a group’s investment in a new employee/associate/partner.

On the other hand, these restrictive clauses have the potential to hurt recruitment and are of unclear enforceability. Many states already limit their scope, and California bans them entirely. A non-compete clause for an employed physician can be used to stifle independent practice and limit physician mobility. It may be used by large systems with their vast resources to maintain a stranglehold on their physicians and employees with their ability to enforce the agreement with limitless legal action.

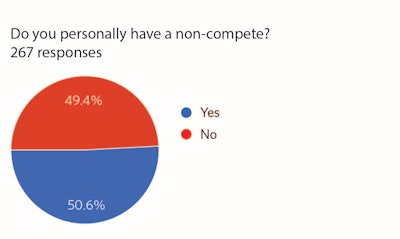

Figure 1

Figure 1

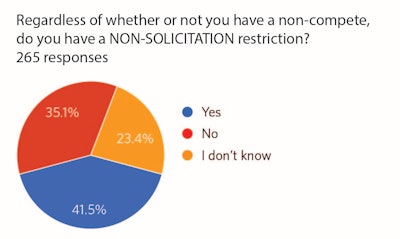

Figure 2

Figure 2

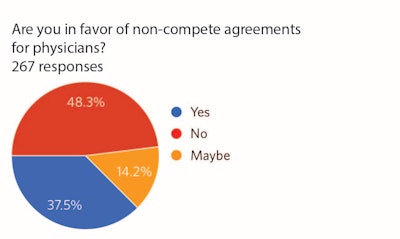

Figure 3

Figure 3

When subdivided by age, those under the age of 45 did not support the use of non-compete clauses (70.5% opposed) and those over the age of 45 were more evenly split (51.5% opposed). In response to whether a non-compete agreement has prevented the respondent from leaving a position, 17.8% responded “yes” or “maybe.”

Of those that had a non-compete, the most cited duration was 18.1 months through 2 years (45.6%), followed by 12-18 months (33%). Only 16.1% had a non-compete longer than 2 years. The most common distance was 15.1-25 miles (24.3%); however, this result is likely to vary by geographic location.

For those who had non-competes and knew the answer, 70.2% are not able to buy themselves out of the restriction. Interestingly, 19% of those who have a non-compete did not know if they were able to purchase themselves out of it.

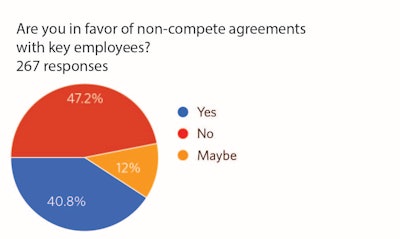

Figure 4

Figure 4

Regarding historic need (within the past 10 years) to enforce covenants not to compete, 9% had to do so with physicians and 73% were successful in doing so. Also, 2.7% attempted to enforce them with employees and 88% were successful.

With essentially a 50-50 split on the support of these contract clauses, there is no definitive PPSG opinion on restrictive covenants. It is hypothesized that the difference in opinion reflects the specific circumstances of each physician’s individual practice. Variables that include personal impact of a non-compete agreement, locoregional physician density, ability to recruit, practice location, history with partners and associates, and the varied roles physicians play in their individual practices (i.e., managing partner) impact an individual’s position.

Regardless of our opinion, this is a controversial topic, and the decision by the federal government will be determined by the judicial system. The adjudicated decision, ultimately, will impact all employee contractual agreements, and physicians will not be immune.