OUT OF COMMITTEE: Outcomes Research and Evidence-Based Medicine | How Advanced Practice Providers Are Shaping Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

Advanced practice providers (APPs), which include physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs), not only have a growing presence within our specialty, but are expanding the overall footprint of otolaryngology-head neck surgery in healthcare.

Elisabeth H. Ference, MD, Victoria S. Lee, MD, and Michael J. Brenner, MD, Chair

Advanced practice providers (APPs), which include physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs), not only have a growing presence within our specialty, but are expanding the overall footprint of otolaryngology-head neck surgery in healthcare. From 2012 to 2017, there was a 51% increase in the number of otolaryngology APPs compared with a 2.2% increase in the number of physician providers.1 There is an expected shortage of 1,620 otolaryngology physicians by 2025 per projections from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.2

Trends

Several factors have fueled the growth in APPs in otolaryngology, which increasingly help to meet the demand for ENT specialty care. Medical systems are seeking ways to stretch the existing physician workforce amid a fixed number of graduating residents. APPs can help meet patient needs amid pressures to expand access while managing expenditures. These needs are particularly acute in rural settings. Moreover, resident work hour restrictions have led to an increased need for help managing inpatients and postoperative patients in academic centers.3 Last, in the community, increasing practice consolidation and the decline of the single-provider practice has led to larger groups with the ability to use and afford APPs.4

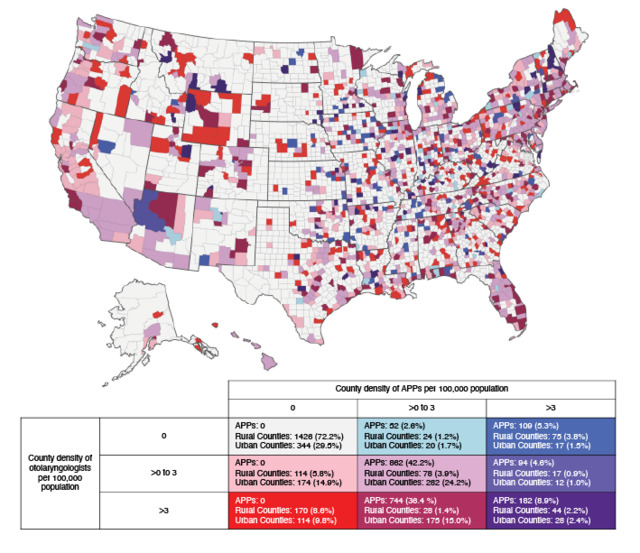

The geographic distribution of otolaryngology APPs differs from that of physicians and surgeons (Figure 1). A majority of rural counties (72%) in 2017 reported zero otolaryngology providers, and a greater proportion of rural counties (5%) were served exclusively by APPs as compared with urban counties (3%).5 Otolaryngology APPs are more likely to practice in rural settings (14%) versus otolaryngology physicians (8%).6 Within otolaryngology, however, states with laws allowing independent practice for NPs did not have a higher proportion of rural NPs, suggesting that state statutes might have only limited influence on APP practice distribution.5

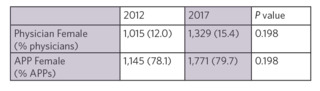

The percentage of female APPs significantly exceeds that of female physicians in otolaryngology (Table 1).1,6 Furthermore, there were no statistically significant trends or changes in the proportion of women APPs or women physicians billing Medicare between 2012 and 2017. In contrast, the increase in female otolaryngologists mirrors the increase of female physicians among all licensed physicians, suggesting that this disparity is a historical remnant likely to change as more women complete training.1

Table 1. Female representation by degree and year Note: Significance testing by multiple regression interaction term.As the number of APPs providing otolaryngology has grown, scope of practice has been stable, focused on common clinic procedures. Between 2012 and 2017, the median number of Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used, number of Medicare reimbursements, number of services, and number of patients per APP showed little change.6 There has, however, been linear growth in total Medicare reimbursements, services, and patient visits by otolaryngology APPs proportionate to growth in the total number of otolaryngologic APPs.6 The most common CPT codes APPs use are 31575 (diagnostic laryngoscopy), 69210 (cerumen removal), 92504 (binocular microscopy), and 31231 (nasal endoscopy). APPs are also performing tympanometry, audiometry, cautery, nasopharyngoscopy, and allergy skin tests at high volumes. The volume of APP services grew faster than physician providers services for all common clinic-based procedures except for balloon sinus dilation and tympanostomy tube placement.5 The number of APPs who performed moderate complexity visits (99202-99204 and 99212-99214) nearly doubled between 2012 and 2017, but few APPs coded for 99215 and 99205, which are reserved for complex patients with high-risk problems.1

Table 1. Female representation by degree and year Note: Significance testing by multiple regression interaction term.As the number of APPs providing otolaryngology has grown, scope of practice has been stable, focused on common clinic procedures. Between 2012 and 2017, the median number of Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used, number of Medicare reimbursements, number of services, and number of patients per APP showed little change.6 There has, however, been linear growth in total Medicare reimbursements, services, and patient visits by otolaryngology APPs proportionate to growth in the total number of otolaryngologic APPs.6 The most common CPT codes APPs use are 31575 (diagnostic laryngoscopy), 69210 (cerumen removal), 92504 (binocular microscopy), and 31231 (nasal endoscopy). APPs are also performing tympanometry, audiometry, cautery, nasopharyngoscopy, and allergy skin tests at high volumes. The volume of APP services grew faster than physician providers services for all common clinic-based procedures except for balloon sinus dilation and tympanostomy tube placement.5 The number of APPs who performed moderate complexity visits (99202-99204 and 99212-99214) nearly doubled between 2012 and 2017, but few APPs coded for 99215 and 99205, which are reserved for complex patients with high-risk problems.1

Few data are available regarding how the pandemic has shaped APP practice in otolaryngology, but anecdotally, many otolaryngologists have observed more patients being referred for problems often handled by primary care providers. As labor shortages and capacity strain have affected the healthcare workforce, both referral patterns and otolaryngology practice have been affected. If some of these trends prove secular, then APPs may assume growing importance in absorbing pent-up demand for care and addressing access for both evaluation and management as well as procedural services.

Types of APPs

Despite differences in governance and education, PAs and NPs overlap in scope of practice within otolaryngology. NPs are registered nurses who have undergone additional master’s or doctoral level training and education, while PAs complete a master’s degree. NPs are governed by a joint committee between the state medical board and nursing board, and PAs are governed by state medical boards. Each state sets the scope of practice standards, with NPs having independent practice authority in 25 states and the District of Columbia. PAs practice under physician supervision but may see patients and bill independently based on state rules.7 Both NPs and PAs have prescribing authority in all states.

From 2012 to 2017, there were no differences in the proportion of NPs and PAs employed by otolaryngology practices (63% PAs in 2012 and 67% in 2017).6 Moreover, 69% of pediatric otolaryngology division chiefs reported no difference in the duties between NPs and PAs on their teams.3 There have been few studies evaluating the quality of care provided by otolaryngology physicians versus APPs, although previous studies have shown evidence of differences in physician versus NP antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric upper respiratory infections.8

Payers reimburse practices for PA or NP services at 85% of the fee schedule for physician services under direct billing. With “incident to” billing, the physician bills and collects 100% of allowable reimbursement; this type of billing can be used when an APP sees a patient who has previously been seen by the physician and has a treatment plan determined by the physician. The physician, however, must be located in the same suite, not just in the same building. Billing for shared/split services allows a practice to bill under the physician, but each provider must document the care that they provide and each must personally perform a substantive portion of the visit. Due to the frequency of APPs billing under a physician, it is difficult to know an APP’s true involvement in otolaryngology care based on Medicare or other billing database studies alone.

Figure 1. Bivariate density map of otolaryngology physicians and APPs per 100,000 people in each county (n=3,142). Otolaryngology APPs are 6% more likely to practice in rural settings compared with physicians. However, there is no association between state laws allowing NP independent practice and the proportion of rural NPs.Optimization of APPs

Figure 1. Bivariate density map of otolaryngology physicians and APPs per 100,000 people in each county (n=3,142). Otolaryngology APPs are 6% more likely to practice in rural settings compared with physicians. However, there is no association between state laws allowing NP independent practice and the proportion of rural NPs.Optimization of APPs

With specialty-specific training, APPs can perform and independently bill for a wide variety of otolaryngology care and procedures either completely independent of physicians or with physician supervision based on state rules. The Mayo Clinic in Arizona was one of the first institutions to offer advanced otolaryngology clinical training to APPs with the creation of a PA fellowship in 2006.9 As more APPs gain clinical training and otolaryngology experience, the role of APPs in care teams has evolved rapidly. APP practice models include fully integrated care teams, collaborative practice with direct supervision, hospital-based inpatient practice, operating room surgical assistance, semiautonomous practice, and independent practice.

Independent practice models, where APPs see patients with little to no direct involvement of a supervising physician, are increasingly common. While these models have the potential to optimize efficiency while providing quality care, full optimization can only be achieved when APPs are members of a physician-led team. Independent models may be fully independent (clinics at a different place or time from the supervising physician, if one is required by state rules) or concurrent (separate roster of clinic patients at the same time and physical location as a supervising physician). In tertiary care centers, the concurrent model has been utilized wherein APPs see a separate roster of patients that requires continued surveillance, initial triage, or medical management; the supervising physician sees a different roster of clinic patients but is immediately available for consultation or even to take over care, if need arises. Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center found that incorporating APPs into head and neck cancer care increased access for new patients, decreased overbooking, and resulted in equal satisfaction among patients seeing an APP versus a surgeon.10 Physician productivity was unchanged. Mayo Arizona found that creating an independent model for a rhinology clinic led to a 200% increase in clinic revenue with increased staff satisfaction.11

Although no single model is appropriate for all practice types or geographic locations, incorporating APPs can improve patient access to specialty care and patient satisfaction.7 Creating a workflow model to maximize reimbursement rates can improve the revenue of a practice. APPs can also increase surgeon’s availability for consults, referrals, surgical cases, and procedures. As the demand for specialty services continues to exceed the physician workforce capacity, especially in rural areas, APPs will play an increasing role in providing otolaryngology care.

References:

1. Ge M, Kim JH, Smith SS, et al. Advanced practice providers utilization trends in otolaryngology from 2012 to 2017 in the Medicare population. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(1):69-75. doi:10.1177/0194599820971186

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and regional projections of supply and demand for surgical specialty practitioners: 2013-2025. December 2016.

3. Chan KH, Dinwiddie JK, Ahuja GS, et al. Advanced practice providers and children’s hospital–based pediatric otolarynology practices. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;129:109770. doi:10.1016/J.IJPORL.2019.109770

4. Quereshy HA, Quinton BA, Ruthberg JS, Maronian NC, Otteson TD. Practice consolidation in otolaryngology: the decline of the single-provider practice. OTO Open. 2022;6(1):1-6. doi:10.1177/2473974X221075232

5. Liu DH, Ge M, Smith SS, Park C, Ference EH. Geographic distribution of otolaryngology advance practice providers and physicians. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;167(1):48-55. doi:10.1177/01945998211040408

6. Patel RA, Torabi SJ, Kasle DA, Pivirotto A, Manes RP. Role and growth of independent Medicare-billing otolaryngologic advanced practice providers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(6):809-815. doi:10.1177/0194599821994820

7. Yalamanchi P, Blythe M, Gidley KS, Blythe WR, Waguespack RW, Brenner MJ. The evolving role of advanced practice providers in otolaryngology: improving patient access and patient satisfaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(1):6-9. doi:10.1177/01945998211020314

8. Ference EH, Min JY, Chandra RK, et al. Antibiotic prescribing by physicians versus nurse practitioners for pediatric upper respiratory infections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(12):982-991. doi:10.1177/0003489416668193

9. Hayden R, Hinni M, Donald C, Perry W. In reference to effective use of physician extenders in an outpatient otolaryngology setting. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(2):548-548. doi:10.1002/LARY.23293

10. Paydarfar JA, Gosselin BJ, Tietz AM. Improving access to head and neck cancer surgical services through the incorporation of associate providers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(5):723-728. doi:10.1177/0194599816647945

11. Sharma N, Upjohn D, Donald C, Zoske KE, Aldridge CL, Lal D. Leveraging advanced practice providers in an otolaryngology practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):959-963. doi:10.1177/0194599820972924