Surgeon Well-Being: Individual, Collegial, and Organizational Perspectives

It is now widely recognized that our well-being as surgeons is critical to us as well as to society for many reasons, such as workforce retention, morale, and productivity; patient safety and quality; and the clinical learning environment.

Jo A. Shapiro, MD, and David J. Brown, MD

In this article, we offer a framework for initiating and sustaining efforts to address surgeons’ well-being.

It is now widely recognized that our well-being as surgeons is critical to us as well as to society for many reasons, such as workforce retention, morale, and productivity; patient safety and quality; and the clinical learning environment. Even if our well-being was not correlated with any such benefits to society, we still deserve, as does everyone, a workplace that allows us to connect to the meaning of our work and supports us as individuals.

Unfortunately, we now know that there is a crisis of well-being in medicine. This is manifested in persistently high rates of physician burnout, depression, and even suicide. Some argue that all of this is due to a lack of fortitude in surgeons today. We strenuously disagree. Although these are not new problems, the stressors in our profession have significantly increased and exacerbated the problems. For example, although duty hour restrictions have helped with sleep deprivation, the intensity and pace of our work has so dramatically increased that the actual work required is of much higher intensity and volume than in years past. The proportion of time spent on meaningful activities, such as direct patient care, has decreased while the administrative aspects of work, such as documentation, have astronomically increased.

Societal expectations of cures as well as intolerance of fallibility have put excessive pressure on us. Disruptive, racist, sexist, or harassing behaviors—from within healthcare providers but also from patients toward healthcare providers—are prevalent. Larger challenges such as healthcare disparities, which have always been present, have also increased in frequency and severity. Some might argue that these disparities have always existed in the same (or higher severity and frequency) but that our awareness and our acknowledgment of their existences has increased. In short, we as individuals are not the problem.

So how do we meet the challenges to our well-being? Most healthcare organizations have been trying to address these challenges by decreasing burnout and improving well-being. These disparate efforts can be confusing and even lead to cynicism when any one effort is perceived to fail to deliver on its promises. We would like to offer a framework to help surgeons participate in, develop, innovate, and assess various approaches to improving our well-being. We will describe the framework and then illustrate how some specific initiatives fit into that framework.

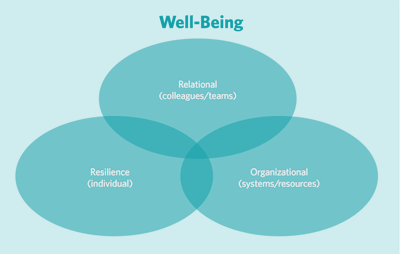

The framework can be visualized as three overlapping Venn diagram circles, each one describing the following initiatives that address different aspects of well-being:

- Individual (resilience)

- Collegial (sense of community)

- Organizational (overarching workplace initiatives and resource allocation)

Individual: These efforts are directed toward facilitating our individual resilience, which can be defined as growth through adversity. There are certain stressors that we as surgeons are highly likely to face at some point in our careers, including medical errors, distressing patient outcomes even with excellent care, litigation, patient aggression, and illness of a colleague. Layered on top of these are chronic stressors, such as mental and physical health disorders, illness, financial pressures, disruptive behaviors, racism, harassment, healthcare disparities for our patients, etc. Most of these are not entirely under our control to prevent, so we need to focus on how we react to them. Resilience strategies include self-care practices, such as exercise and healthy diet and stress reduction approaches, such as meditation and gratitude practices. It is important to state, however, that the responsibility for well-being cannot rest on our individual shoulders. It is unfair for us to individually bear the burden for some aspects of surgery that need wider approaches.

Collegial: Most of us derive significant joy from the support and sense of community that come from our colleagues. We need only think back to residency when, despite the responsibilities and heavy workloads, we felt buoyed by our fellow residents and mentors. Once we begin our lives post-training, however, there are fewer opportunities to connect with colleagues. In addition, many institutions have eliminated gathering spaces, such as physicians’ and/or surgeons’ lounges and cafeteria sections. Practicing surgery can be quite isolating, perhaps more so for rural surgeons and those practicing in more isolated settings. Some well-being initiatives have provided opportunities for colleagues to gather and reconnect, such as monthly dinners with structured discussions.

Organizational: Clearly, there are many aspects of practicing surgery that depend on our organizations, including workflow issues, documentation burdens, electronic health record structures, resource allocation, equipment and infrastructure, and addressing racism, discrimination, disruptive behaviors, and other threats to workplace safety, both psychological and physical. Local and national organizations need to take responsibility for leading efforts to address these challenges.

We will use three examples of well-being challenges and show how specific initiatives to address these challenges fit into the framework detailed above.

Acute Stressors: As mentioned, the practice of surgery is both highly rewarding and, at times, highly stressful. Acute events such as medical errors, litigation, and patient aggression are known to cause significant emotional impact on the involved clinicians. Research has shown that in response to such stressors, physicians want to be supported by physician colleagues rather than mental health providers. In response, many organizations have developed peer support programs to provide proactive outreach for either one-on-one or group peer support. Looking at the framework of well-being initiatives, peer support sits at the intersection of the three circles: aiding individual resilience by helping peers navigate and strategize in the face of adversity, promoting collegiality by having the support come from a colleague who understands the pain, and organizational responsibility by having the institution resource the peer support program as well as responding to systems issues that may become evident in the peer support intervention.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Challenges: The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted numerous inequities in addition to healthcare disparities. Women were disproportionately tasked with childcare, homecare, and homeschooling in addition to their professional careers. Minoritized individuals shouldered the additional burdens of advocating for patient equity and doing most of the diversity, equity, and inclusion education (formally and informally), all while experiencing bias, discrimination, harassment, homophobia, and racism in their personal and professional lives. These additional “taxes” decrease our well-being.

Implicit biases are ubiquitous in our society, career pathways, and work environments. These biases can obstruct advancement, forcing woman and minoritized individuals to work harder to achieve their goals and aspirations. This adds extra stress to a profession that is experiencing significant burnout at baseline. Implicit bias training is only the first step in raising the awareness of our biases. We must continue to acknowledge that biases exist, hold ourselves and others accountable for biased practices, and actively model behaviors and actions that combat their negative influences.

Harassment and microaggressions continue to be experienced in the workplace and are perpetrated by peers, superiors, learners, and patients. These unwanted aggressions decrease our mental health and increase burnout. Although there are tools and tactics for recipients to respond to harassment and microaggressions, the response and restoration burden cannot only be on the target, but also needs the support of allies to put into action the skills learned from bystander/upstander trainings. Additionally, institutions can help by utilizing easy-access reporting systems that are free from retaliation and accountable to timely assessments, professional development, corrective actions, and positive culture reinforcements.

One opportunity to increase well-being is to build a sense of belonging, which comprises feelings of acceptance, connectedness, and being valued by the group. Belonging is not only associated with increased well-being, but it also increases employee engagement, performance, and retention. Teams and institutions can support belonging by ensuring psychological and emotional safety, creating an environment that is welcoming, celebrating the unique contributions from each person, and honoring diversity, equity, and inclusion at all times.

Cultural humility enhances belonging and well-being by engaging others in humble, authentic, and mindful active listening. The term was coined in 1998 by Melanie Tervalon, MD, MPH, and Jann Murray-García, MD, MPH, as a tool to positively enhance the relationship between physicians and patients of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Cultural humility is a lifelong commitment to learning and self-reflection that recognizes, challenges, and mitigates power imbalances while building mutual respect, partnership, and trust. It is now being practiced in the workplace and leads to better communication, increased well-being, improved mental health, and reduced interpersonal conflict.

Musculoskeletal Injuries: We know that surgeons are at an elevated risk for occupational musculoskeletal injuries, including cervical and lumbar spine, as well as carpal tunnel. In our AAO-HNSF 2021 Annual Meeting Panel Presentation addressing well-being, we invited a presentation by a physical therapist who has expertise in surgeon musculoskeletal health. Recommendations such as preventative stretching, strengthening, and breathing exercises fall into the individual sphere. Organizational responsibilities include providing education to all surgeons, including trainees, on mitigating the risk of musculoskeletal injuries; providing ergonomically sound equipment, including meeting the needs of women surgeons and others with varying body types such as hand size; and facilitating treatment access to surgeons who sustain musculoskeletal injuries.

Supporting surgeons’ well-being and decreasing burnout require sustained and multipronged efforts. It is our hope that as individuals, colleagues, and organizations, we will all continue to find ways to engage and innovate in various well-being initiatives.