OUT OF COMMITTEE: Voice | Gender-Affirming Voice Care Defined and in Practice

Creating a welcoming and gender-affirming environment requires training, nondiscrimination policies, and cooperation among the entire healthcare team.

With recent increasing numbers of transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people of myriad gender expressions seeking voice care, many otolaryngologists and speech-language pathologists find themselves serving a community they may know little about. Gender-affirming care extends well beyond the advanced technical skills required to help someone change the sound of their voice. It requires a humble understanding of the diversity of gender expression, advanced counseling skills, and a readiness to uniquely tailor the support to the individual’s needs.

The authors acknowledge that although this article was written with the leadership of our one transgender team member, this topic requires the leadership of many TGNC people of diverse lived experiences. Thus, this article is a starting point for conceptualizing gender-affirming voice care for the otolaryngologist, to be expanded upon in the future.

Responsibilities of the Gender-Affirming Healthcare Provider: Beyond Clinical Skills

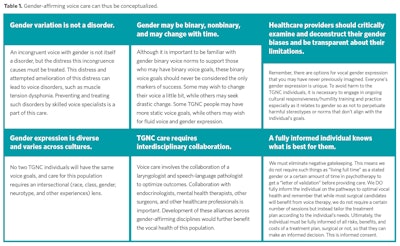

Healthcare providers play a gatekeeping role. Our decisions and recommendations inform the type, duration, and quality of care an individual receives. The transgender community has experienced a long history of negative gatekeeping from healthcare providers that continues today. Individuals often face barriers to accessing gender aligning healthcare. When treating transgender people, it is, therefore, not enough to be an expert in one’s chosen specialty. Healthcare providers must be gender-affirming practitioners. (See Table 1.)

Gender-affirming practitioners recognize that 1) gender variation is not a disorder; 2) gender is diverse and varied across culture and thus requires cultural sensitivity and responsiveness); 3) gender may be binary or not binary and may be fluid over time.1 Furthermore, 4) gender-affirming care requires interdisciplinary collaboration in which 5) providers deconstruct and are transparent about their biases about gender and the binary.2 Finally, gender-affirming practitioners eliminate negative gatekeeping by working under the assumption that 6) a fully informed individual (in this case, the person seeking care) knows what is best for them.3, 4

Gender Expression

Gender can be binary (man versus woman) or nonbinary (neither male or female, genderfluid, genderqueer, agender, and more), and its expression is diverse and unique to each individual. There is no one way to be feminine, masculine, or nonbinary, and transgender individuals may wish to change their voice a lot, a little, or not at all. Although some normative data exist on what is perceived as feminine or masculine through characteristics of pitch, resonance, and intonation, there is no “correct way” to communicate to express one’s gender. Therefore, it is critical that the gender-affirming clinician listens to the communication goals of the patient so that their care recommendations align with their patient’s.

Clinically relevant tools are available to assist the gender-affirming healthcare provider in assessing the communication goals of the TGNC patient. Along with a thorough history and patient interview, using validated patient-reported outcome measures, such as the Trans Woman Voice Questionnaire, the Voice Handicap Index-10 or Voice-Related Quality of Life Index, and the Vocal Fatigue Index, are helpful in identifying specific current voice complaints and future voice and communication goals.

Medical and Surgical Intervention for the Gender-Affirming Patient

Medical and surgical intervention for transgender voice is limited to changing pitch. Lowering the pitch is often achieved with the use of testosterone. There can be a role for cricothyroid muscle paralysis or division as well as laryngeal framework surgery (Isshiki type III thyroplasty). Surgical procedures for pitch elevation aim to decrease the length and size of the vocal folds. The most common procedure is the endoscopic glottoplasty or Wendler glottoplasty, which creates an anterior glottic web to shorten the length of the vocal folds. Cricothyroid approximation is framework surgery that increases vocal fold tension, elevating pitch. Laser reduction glottoplasty decreases true vocal fold size or bulk. As with all laryngeal surgical interventions, there is the risk of worsening voice, dysphagia, and need for revision procedures. Specific risks of these procedures include reduction or loss of singing voice range and reduced loudness, which should be discussed during surgical consultation.

It has been well established that altering pitch alone is not sufficient for most people to achieve a gender congruent voice. In most cases, gender-affirming voice therapy to address other targets such as resonance, timbre, and more, is necessary for individual satisfaction. Furthermore, voice therapy is necessary to optimize wound healing and help the patient balance their breathing, phonatory, and resonance systems for efficient use of the altered anatomy. Without this therapy, the patient may develop maladaptive compensatory strain leading to suboptimal surgical results and overall dissatisfaction.

Behavioral Intervention for the Gender-Affirming Patient

As with medical and surgical care, gender-affirming voice therapy must be provided by a voice-specialized speech-language pathologist who has sought additional training in intersectional TGNC cultural responsiveness, as well as advanced gender-affirming voice skills. The literature on voice treatment for the transgender patient cites anywhere from 4.8 to 12 therapy sessions but is highly patient-specific and may be shorter or longer based on the patient’s communication needs and speed of progress toward meeting those needs.5, 6 As with all behavioral voice interventions, the ultimate goal is functional use of the target voice across various communicative activities of daily living. For the transgender patient, individual treatment goals may include identifying and maintaining gender-congruent pitch and resonance and may or may not extend to intonation, articulation, and/or nonverbal communication strategies. Frequent check-ins with the patient on how treatment sessions are or are not in line with their stated communication goals is critical for patient-provider calibration on the long-term goal and efficient use of patient healthcare resources.

Summary

Voice can be a critical aspect of gender affirmation. It can affect both self-identification and gender perception by others. The multidisciplinary team of skilled laryngologists and voice-specialized speech language pathologists can help transgender patients reach their communication goals. Healthcare providers must maintain an awareness of their patient’s individual needs, as well as their own personal biases that may impede care. Creating a welcoming and gender-affirming environment requires training, nondiscrimination policies, and cooperation among the entire healthcare team.

Important Reminders and Take-Aways

- Research has demonstrated that alteration of pitch alone is insufficient in achieving a gender-aligned voice.

- Surgical limitations and risks, such as loss of upper singing voice range, reduced loudness, and need for revision, are important to discuss with the patient so that they can make a fully informed decision about what is best for them.

- Individuals may wish to change their voice a lot, a little, or not at all. They may wish to change their voice permanently, or in some situations only.

- Many people achieve their vocal goals with voice therapy only. If surgical options are pursued, voice therapy plays an important role in rehabilitation of the voice as well as with addressing other gender-affirming targets.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration with speech-language pathology is necessary for optimal voice outcomes.

References

1. Hidalgo, M. A., Ehrensaft, D., Tishelman, A. C., Clark, L. F., Garofalo, R., Rosenthal, S. M., Spack, N. P. & Olson, J. (2013). The Gender Affirmative Model. Human Development, 56(5), 285-290.

2. Edwards-Leeper, L., Leibowitz, S., & Sangganjanavanich, V. F. (2016). Affirmative practice with transgender and gender nonconforming youth: Expanding the model. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 165.

3. Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., et al. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International journal of transgenderism, 13(4), 165-232.

4. Ehrbar, R. D., & Gorton, R. N. (2010). Exploring provider treatment models in interpreting the standards of care. International Journal of Transgenderism, 12(4), 198-210.

5. Park C, Brown S, Courey M. Trans Woman Voice Questionnaire Scores Highlight Specific Benefits of Adjunctive Glottoplasty With Voice Therapy in Treating Voice Feminization. J Voice. 2021 Sep 23:S0892-1997(21)00256-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.07.017. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34565626.

6. Quinn S, Oates J, Dacakis G. The Experiences of Trans and Gender Diverse Clients in an Intensive Voice Training Program: A Mixed-Methodological Study. J Voice. 2021 Feb 2:S0892-1997(21)00019-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.12.033. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33546939.