FEBRUARY IS KIDS ENT HEALTH MONTH | COVID-19 in Children: Severity, Sequelae, and Vaccine Update

Since early 2019, the world has witnessed the rise of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) that has culminated into a global pandemic.

Mathieu Bergeron, MD, Committee member

Heather C. Herrington, MD, Committee Chair

Note: This article includes data current at the date of publication.

Since early 2019, the world has witnessed the rise of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) that has culminated into a global pandemic. Within the United States, the first case of COVID-19 was initially reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on January 20, 2020, in the state of Washington.1

From the start of the pandemic to the time this article was published, the U.S. population alone has experienced 51,500,000 cases of COVID-19, equating to an infection rate of 15.6% of the U.S. population in <2 years. When considering minimally or asymptomatic Americans (potentially untested for COVID-19), it is estimated that 103,000,000 (one in three) Americans may have been infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus before the end of 2021. Tragically, this is well before the advent of the Delta virus strain or Omicron strain, both of which are currently circulating within the U.S. Overall, approximately 860,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 since the pandemic began.2 Globally, COVID-19 is thought to have infected over 252,000,000 people and resulted in 5.11 million deaths, with the U.S. leading in COVID-19 deaths worldwide.3

COVID-19 symptoms commonly include respiratory symptoms such as dry or productive cough, shortness of breath, fevers, chills, fatigue, rhinorrhea, muscle and body aches, sore throat, headache, and new loss of taste or smell. Some people may present with primarily gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea prior to lower respiratory tract symptoms.

In most individuals, acute COVID-19 symptoms appear 2-14 days after exposure and often improve within 14 days.4 Rarely, long-term symptoms lasting greater than 3-6 months following COVID-19 infection (i.e., long COVID) have been found to persist in approximately 33%-50% of individuals.5,6

Compared to adults, children often have milder COVID-19 symptoms that can mimic the “common cold,” or they may even have no symptoms at all. Although children may have few symptoms, their viral loads can be as high as symptomatic adults with COVID-19, and children can spread the disease. COVID-19 can also infect infants and neonates, and like other viruses, it can cause more symptoms in this age group because of their small airways.

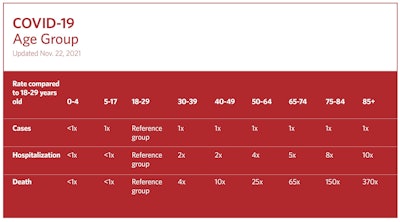

Overall, U.S. children have been reported to represent about 17.3% of all COVID-19 cases nationally, although this proportion is continuing to rise with the spread of the Delta and Omicron COVID-19 strains.7 Children most at risk for severe illness from COVID-19 include those with other health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, asthma, congenital heart disease, genetic conditions, or conditions affecting the nervous system or metabolism. Currently there is much speculation about why children contract COVID-19 less frequently and symptomatically than adults. Many theories revolve around the suspicion that children are afforded more baseline overlapping protection against COVID-19 given their frequent exposure to similar non-SARS-CoV-2 or respiratory viruses encountered during childhood. Other theories involve potentially a less mature immune system, differential expression of pulmonary angiotensin-converting enzyme receptors to which the virus binds, and children’s different systemic reaction to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.7

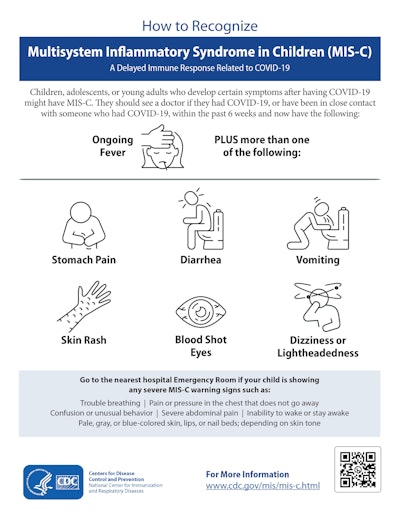

In children, a rare but serious late complication of COVID-19 infection is the development of MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children). MIS-C causes inflammation that can affect the heart and lungs, blood vessels, kidneys, digestive system, brain, skin, and eyes, and can occur about two to six weeks after infection. Treatment involves quick recognition, hospitalization, and management with intravenous immunoglobulin, steroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

We do not yet understand what triggers some children with prior COVID-19 infection to develop MIS-C.8 Frequent signs and symptoms of MIS-C include fever, GI symptoms, tachycardia/tachypnea, tiredness, redness of the hands/feet, swelling, and redness of the lips and tongue. If a child develops these symptoms, particularly after a known COVID-19 infection or exposure, they should be evaluated immediately. A large ratio of children with MIS-C may require intensive care because of low blood pressure, but often this is not fatal.

Children are protected from COVID-19 infection in much the same way as adults. Social distancing, masking, frequent handwashing, and vaccination are the best ways to protect children and vulnerable individuals from COVID-19 infection. In children who are too young to be vaccinated, ensuring that those around them are vaccinated and practice the above precautions is the best way to protect this vulnerable population. While initially there was some concern that vaccination may put children—particularly boys—at higher risk for side effects from COVID-19, we now know that the risk of side effects, such as myocarditis, with vaccination is low and treatable with simple interventions such as ibuprofen (Advil) administration.9

One of the most common ENT manifestations of COVID-19 infection is loss of smell. Other manifestations of COVID-19 include facial palsy or sudden hearing loss that have been reported in adults and very rarely in children.4 Loss of taste and smell after COVID-19 infection is a common complaint and can affect ~50% of individuals infected. It is thought that loss of smell results from infection of the sustentacular cells (supportive cells) around the olfactory neurons that are responsible for one’s sense of smell. Both the olfactory neurons and the surrounding sustentacular cells are located within the uppermost regions of both nasal cavities. As SARS-CoV-2 virus is a respiratory virus, infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus occurs from breathing it into the body, often through the nose. The SARS-CoV-2 virus primarily targets the sustentacular cells and olfactory neurons to cause infection. When exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the sustentacular cells are primarily targeted and destroyed by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the body’s immune response to it. These cells may take two to four weeks to start to regenerate from precursor cells, i.e., stem cells, within the area of the olfactory nerves. Hence, in many individuals after COVID-19 infection, it may take about one to six months for many individuals’ sense of taste and smell to improve. In a small minority of patients, return of taste and smell may never occur. While many medications are often tried to help recover patients’ loss of taste and smell after COVID-19 infection, none are frequently effective. In individuals with prolonged loss of taste and smell after COVID-19 infection or who develop new phantom/abnormal smells or tastes, practicing “smell therapy” can be helpful to retrain and reeducate the body to familiar tastes and scents.

Within the pediatric population, protection from COVID-19 infection over the past two years has included similar strategies to those practiced by adults. This has included social distancing in public settings, frequent handwashing, and masking when unable to socially distance. Since December 11, 2020, vaccination of older children with Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna has occurred, with expansion to children 5-11 years old beginning October 29, 2021. With current uncertainty regarding the Omicron variant and its potential transmissibility to children, the best line of defense against infection from all strains of COVID-19 still involves vaccination of all eligible children and adults in the U.S., in addition to continued attention to social distancing, masking, and frequent handwashing.

National Center For Health Statistics. Centers For Disease Control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/

References

1. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html. Updated November 2021. Accessed December 2021.

2. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. CDC COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days. Updated January 2022. Accessed January 2022.

3. World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Updated December 23, 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Updated February 2021. Accessed November 2021.

5. Medical News Today. More than one-third of COVID-19 patients may experience long COVID symptoms. October 5, 2021. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/more-than-one-third-of-covid-19-patients-may-experience-long-covid-symptoms

6. Science Daily. How many people get ‘long COVID’? More than half, researchers find. October 13, 2021. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/10/211013114112.htm

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: state-level data report. Updated December 16, 2021. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19. Updated September 20, 2021. Accessed November 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-c.html

9. Das BB, Kohli U, Ramachandran P, et al. Myopericarditis after messenger RNA Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination in Adolescents 12 to 18 years of age. J Pediatr. 2021;238:26-32.