The Making of a Physician, a Surgeon, and an EVP/CEO: David R. Nielsen, MD

By M. Steele Brown David R. Nielsen, MD, never planned any of this. He did, how- ever, work hard to get here. The Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and its Foundation, Dr. Nielsen—one of 11 children—several of them trial attorneys, did not grow up dreaming of becoming a physician. “When I started college, I had no idea what I wanted to do for a living,” he said. “I did know I did not want to be a lawyer. Frankly, most of the things I’ve accomplished in my life I didn’t intentionally set out to do from the beginning, and choosing medicine is probably a good example.” A Lofty Goal The medical school option began to crystallize strangely enough after a self-described “lousy” first year at the University of Utah, where he “spent too much time skiing and not enough time attending class or doing homework.” On scholarship from an insurance company executive who valued education, Dr. Nielsen decided it was time to grow up and get to work, even if he had no clear idea what that work should look like. “So I set a goal so lofty that I’d still be better off than I was in the first place if I didn’t make it,” he said. “I thought, ‘OK, medical school’s a lofty goal, but I don’t really know what it means to be a doctor, but that’s OK. I’ll see whether or not this is for me.’ I decided a business degree would be good to have as a back-up.” Unfortunately, Dr. Nielsen’s advisor believed that lackluster first year was going to be tough to overcome and told him to abandon medicine. Dr. Nielsen was determined to try. “His response was, ‘OK, if you want to do this…you will go to every one of your professors at the beginning of the semester and ask them to write you an evaluation and a personal letter of recommendation at the completion of the class.” So Dr. Nielsen had the conversation with every professor, every semester. “I know I annoyed the heck out of them, but every one of them wrote me one,” he said. When he finally applied to the University of Utah School of Medicine, Dr. Nielsen had a 4.0 GPA, as well as a phone book- thick folder of those letters. Even after the hard work and good grades, Dr. Nielsen still didn’t believe he would get accepted. Yet he did and that, as he puts it, “created a conundrum for me because I knew nothing about medicine.” Making an ENT At the same time he’d been studying, Dr. Nielsen also had been working for a family neighbor—an orthopedic surgeon—as an office assistant. “I worked mornings for him and took a bus up to campus in the afternoon or evening every day for a couple years,”Dr. Nielsen said. “By the time I was done, I was doing all of his cast work and taking care of all of his traumas. So, when I first went to medical school, I was going to be an orthopedic surgeon.” That notion changed in his third year. “I had a couple of weeks of elective to fill and I just picked ENT out of the hat.” Working with a microscope, Dr. Nielsen discovered he had real skills with his hands. “It’s like building ships in a bottle,” he said. “The head and neck is just so full of anatomy, and it’s really tiny, delicate work—even breathing or sweating is enough to throw you off. Not everybody can do it and I just fell in love with it.” Dr. Nielsen discovered his love of otology during his residency at Utah, which featured one of the world’s first laser labs. “John Dixon, MD, was doing some pioneer work with lasers treating esophageal varices and stomach problems in general surgery, and there weren’t many laser applications being used in the head and neck back then, but our department was starting to use them for lesions of the tongue and the nose and to excise some cancers,” he said. “Then I discovered there were a couple of pioneers using the laser to do these microscopic ear procedures that hadn’t really been accepted yet.” One of those pioneers, Ted McGee, MD, had developed a technique for using a laser to perform a stapedectomy at his practice in Detroit. “He had a fellowship program, and I went to work with him doing laser stapes work,”he said. “In fact, Providence Hospital had just started to do laser surgery, and I actually wrote the laser safety manual for the hospital.” Arizona Highways In 1984, Dr. Nielsen set up a solo otology practice in Phoenix. About 13 years later, he became a senior consultant at the newly built Mayo Clinic campus in Scottsdale where he stayed until he joined the Academy in 2002. Early on in his solo career, Dr. Nielsen got a call from former AAO-HNS President Neil O. Ward, MD, MALS, then president of the Arizona Medical Association. Dr. Ward was looking to start a young physician section. “He invited 30 or 40 young doctors and six of us showed up,”Dr. Nielsen said. “The new section had six officer positions, so every one of us got one.” As a result, Dr. Nielsen attended American Medical Association (AMA) meetings as a delegate and got to know people. “I’d listen to Dr. Ward talk about health policy and legislation and government affairs and think, ‘Oh man, how does he know so much?’” Dr. Nielsen said. “He told me that the only school for learning is to get involved and participate.” Dr. Nielsen did and eventually was elected chair of the AAO-HNS Board of Governors, which gave him a seat on the Academy’s Board of Directors. The Road to Alexandria When former EVP Michael D. Maves, MD, MBA, left the AAO-HNS in 1999 to join the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, several people encouraged Dr. Nielsen to apply. “It seemed like everyone who had served in that position in the last 100 years had either been a dean or a department chair or program director,” Dr. Nielsen said. “We’d never had anybody from the West; and solo private practitioners don’t preside over anyone beside their nurse and their assistant. I didn’t take it seriously until I got a call from someone at the (Academy) saying I should apply.” Dr. Nielsen applied, confident that he would not be chosen, but certain it would be good to “stretch my wings a little bit and see,” he said. The person who did get it, G. Richard Holt, MD, whom Dr. Nielsen describes as “an absolutely spectacular man,” like Dr. Maves, chose another career path. “The (then) president of the Academy, KJ Lee, MD, who was chairing the search committee, called and said I should apply,” Dr. Nielsen said. “My youngest son was just graduating high school and we figured that if we were going to do something like this, now was the time.” This time the offer came and he accepted. Visionary Changes In Dr. Nielsen’s view, both the Academy and the specialty of otolaryngology—head and neck surgery have changed more in the last 12 years than they did in the previous century. As one of the smallest (in terms of membership) of the 24 primary specialty societies, Dr. Nielsen said he is proud of the range of services the AAO-HNS provides. “We do it all—practice management, IT, health policy, state and federal regulatory and legislative affairs, research, education, and the best meeting in the world—and the cost of that is roughly the same as it is for other societies, but we have to spread that out over just 10,000 doctors,” he said. “We have learned to become more effective or efficient as a staff and we require and benefit from a much higher level of volunteerism from our members than many other societies. That’s been quite successful.” Compared to 12 years ago, Dr. Nielsen said the Academy has doubled the amount of work it is doing, even though it has reduced staff levels from 87 to 64 people since 2002. “We now have a department that combines research, quality and health policy, as well as an IT (now called Information and Knowledge Management) unit that was paired down by half, but is now much more effective and efficient offering support around various processes, including the new website and community portal,” he said. “Overall, we’re doing a lot of things that we couldn’t do 12 years ago and we are doing them with more efficiency.” He also takes pride in the Academy’s increased visibility and voice. “We’ve gone from being kind of invisible in certain conversations to being sought out,” he said. “Government agencies and other organizations want to hear our ideas about healthcare, delivery, and payment reform. The respect we are given, owing to the Academy’s involvement in issues and our evidence-based opinion, has gone up dramatically.” Quality Is Job No. 1 Nowhere can this increased visibility be seen more than in the area of quality and evidence-based guidelines, according to Dr. Nielsen. In the past decade, the AAO-HNS has become extremely skillful in addressing quality medicine in a formal way. The Academy has always had good doctors who care more about quality than about anything else, he said, but it never had a systematic, organized method of approaching or documenting the quality the specialty and its physicians offered. When Dr. Nielsen took over in 2002, he mobilized the leaders of all the subspecialty societies in otolaryngology to develop evidence-based guidelines for the specialty that could take up the challenge issued by the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC). “To have your guidelines published, they have to be of a certain rigor, meet a certain set of criteria; you can’t just make up a guideline and have the NGC publish it,” Dr. Nielsen said. “When we started this push, there were dozens and dozens of guidelines related to otolaryngology, and not a single one of them had been accepted by the NGC and none of them had been produced by the Academy.” The AAO-HNSF has now produced more than a dozen NGC-published guidelines and has been cited by both the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies (CMSS) as an example of how best to produce effective and appropriate evidence-based standards. The Academy has also diverted its resources to support more broadly based research, instead of focusing exclusively on the basic sciences and clinical translational research. “We still maintain our support for those types of research, but we’ve expanded to health services research—focusing on how we get from the bedside into systems and populations so we can eliminate unwanted variations in healthcare and outcomes for the sake of improving public health.” Dr. Nielsen said that with all of the changes taking place with regard to how healthcare is delivered, the Academy wants to make sure quality doesn’t suffer. “There’s a real temptation for physicians and physician organizations to start checking boxes,” he said. “If we’re going to (offer care), we’re going to do it because it really makes patients better. We also want to aggregate the demand, because if we’ve set our standards so high that we exceeded everybody else’s, we are in pretty good shape.” The Transition When Dr. Nielsen turns his office over to the new EVP/CEO, James C. Denneny III, MD, on January 15, 2015, it will cap off a transition plan that has been in the works for more than year. “I sat down with the executive leadership team a year ago to get processes in place and I told them my retirement could not be a distraction because we had too much work to do.”Dr. Nielsen said he started by having open conversations with senior leaders on staff to minimize any disruptions. “I want my staff to feel secure and know they’re supported, because whatever we’ve changed, whatever we’ve accomplished, it isn’t me that’s accomplishing it,” Dr. Nielsen said. “It’s this incredible staff around me, and the thousands of doctors who make life-and-death decisions every single day and put in long hours and then, when they’re done, devote more time and energy and creativity and effort to the Academy. They give up their weekends and holidays with their families to do that. All we’ve accomplished has really been done by these people, and our success is really based on that.” Dr. Nielsen said while it will be most important for the staff to help on board Dr. Denneny, he also outlined how he spends his days to give Denneny a sort of playbook to which he can refer. “I kept a log of how I spend my days—where I traveled, how I spent my days for the last year-and- a-half—and I’ll hand that off,” he said. “You can see my estimate of the hours that I spend on the College of Surgeons, the AMA, the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), the CMSS and all the other alphabet soup of meetings I attend.” He also wrote his successor an executive summary of just what goes on at the Academy. “I wrote it so he could read through it within 30 minutes and get a fair overview of what the Academy does,” he said. “I want this to go so smoothly that next year at this time, people say, ‘Is he gone? I didn’t realize that,’” Dr. Nielsen said. The Future From here, Dr. Nielsen said he has a lot of options, but no formal plan in place. “I’d like to serve a mission for the (Mormon) church with my wife, Rebecca,” Dr. Nielsen said. “And since all of our four children and 12 grandchildren have moved back to Arizona within 50 miles of each other, it’s time to get back there to see them.” On the work front, Dr. Nielsen said it is too early to tell what he’s going to do next. “Right now I have plenty of work to do for 2015,” he said. “I’ll be busy fulfilling obligations (to organizations such as PCPI and CMSS).” But he does say this with certainty to the members, “I have spent more than a decade in your debt for the honor of being allowed to serve with our excellent staff and our outstanding specialty leaders. And between now and the end of the year, it will be time for me to perform the last responsibility of a leader—to say thank you. “Thank you for your membership in the Academy. Thank you for your trust—in me, in your fellow Academy members, in your leaders, and in your staff. And most of all, thank you for your dedication to medicine and to your patients.” And now, it is our turn to say thank you to Dr. Nielsen, Thank you for sharing and caring. Thank you for your knowledge and vision, for your passion and dedication. Thank you for making a difference and for helping to ensure that when the next generation comes along, we hand them tomorrow’s Academy.

David R. Nielsen, MD, never planned any of this. He did, how- ever, work hard to get here.

The Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and its Foundation, Dr. Nielsen—one of 11 children—several of them trial attorneys, did not grow up dreaming of becoming a physician.

A Lofty Goal

The medical school option began to crystallize strangely enough after a self-described “lousy” first year at the University of Utah, where he “spent too much time skiing and not enough time attending class or doing homework.” On scholarship from an insurance company executive who valued education, Dr. Nielsen decided it was time to grow up and get to work, even if he had no clear idea what that work should look like.

Unfortunately, Dr. Nielsen’s advisor believed that lackluster first year was going to be tough to overcome and told him to abandon medicine. Dr. Nielsen was determined to try.

In 1994 during the Arizona years, Dr. Nielsen served as national campaign chair for the AAO-HNS campaign against secondhand smoke. Its kick-off event speakers included: (left to right) then U.S. Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders, MD; Joan Lunden, campaign spokesperson and host of “Good Morning America”; Academy EVP Jerome C. Goldstein, MD; David Nielsen, MD; and Nancy Snyderman, MD, “Good Morning America” correspondent.

In 1994 during the Arizona years, Dr. Nielsen served as national campaign chair for the AAO-HNS campaign against secondhand smoke. Its kick-off event speakers included: (left to right) then U.S. Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders, MD; Joan Lunden, campaign spokesperson and host of “Good Morning America”; Academy EVP Jerome C. Goldstein, MD; David Nielsen, MD; and Nancy Snyderman, MD, “Good Morning America” correspondent.“His response was, ‘OK, if you want to do this…you will go to every one of your professors at the beginning of the semester and ask them to write you an evaluation and a personal letter of recommendation at the completion of the class.”

So Dr. Nielsen had the conversation with every professor, every semester. “I know I annoyed the heck out of them, but every one of them wrote me one,” he said.

When he finally applied to the University of Utah School of Medicine, Dr. Nielsen had a 4.0 GPA, as well as a phone book- thick folder of those letters.

Even after the hard work and good grades, Dr. Nielsen still didn’t believe he would get accepted. Yet he did and that, as he puts it, “created a conundrum for me because I knew nothing about medicine.”

Making an ENT

At the same time he’d been studying, Dr. Nielsen also had been working for a family neighbor—an orthopedic surgeon—as an office assistant.

“I worked mornings for him and took a bus up to campus in the afternoon or evening every day for a couple years,”Dr. Nielsen said. “By the time I was done, I was doing all of his cast work and taking care of all of his traumas. So, when I first went to medical school, I was going to be an orthopedic surgeon.”

That notion changed in his third year.

“I had a couple of weeks of elective to fill and I just picked ENT out of the hat.”

Working with a microscope, Dr. Nielsen discovered he had real skills with his hands.

Dr. Nielsen discovered his love of otology during his residency at Utah, which featured one of the world’s first laser labs.

“John Dixon, MD, was doing some pioneer work with lasers treating esophageal varices and stomach problems in general surgery, and there weren’t many laser applications being used in the head and neck back then, but our department was starting to use them for lesions of the tongue and the nose and to excise some cancers,” he said. “Then I discovered there were a couple of pioneers using the laser to do these microscopic ear procedures that hadn’t really been accepted yet.”

One of those pioneers, Ted McGee, MD, had developed a technique for using a laser to perform a stapedectomy at his practice in Detroit.

“He had a fellowship program, and I went to work with him doing laser stapes work,”he said. “In fact, Providence Hospital had just started to do laser surgery, and I actually wrote the laser safety manual for the hospital.”

Arizona Highways

Early on in his solo career, Dr. Nielsen got a call from former AAO-HNS President Neil O. Ward, MD, MALS, then president of the Arizona Medical Association. Dr. Ward was looking to start a young physician section.

“He invited 30 or 40 young doctors and six of us showed up,”Dr. Nielsen said. “The new section had six officer positions, so every one of us got one.”

As a result, Dr. Nielsen attended American Medical Association (AMA) meetings as a delegate and got to know people.

“I’d listen to Dr. Ward talk about health policy and legislation and government affairs and think, ‘Oh man, how does he know so much?’” Dr. Nielsen said. “He told me that the only school for learning is to get involved and participate.”

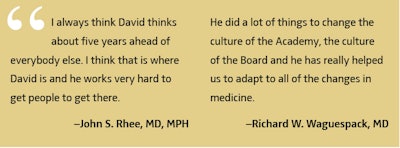

Dr. Nielsen did and eventually was elected chair of the AAO-HNS Board of Governors, which gave him a seat on the Academy’s Board of Directors.

The Road to Alexandria

When former EVP Michael D. Maves, MD, MBA, left the AAO-HNS in 1999 to join the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, several people encouraged Dr. Nielsen to apply.

“It seemed like everyone who had served in that position in the last 100 years had either been a dean or a department chair or program director,” Dr. Nielsen said. “We’d never had anybody from the West; and solo private practitioners don’t preside over anyone beside their nurse and their assistant. I didn’t take it seriously until I got a call from someone at the (Academy) saying I should apply.”

Dr. Nielsen applied, confident that he would not be chosen, but certain it would be good to “stretch my wings a little bit and see,” he said.

The person who did get it, G. Richard Holt, MD, whom Dr. Nielsen describes as “an absolutely spectacular man,” like Dr. Maves, chose another career path.

“The (then) president of the Academy, KJ Lee, MD, who was chairing the search committee, called and said I should apply,” Dr. Nielsen said. “My youngest son was just graduating high school and we figured that if we were going to do something like this, now was the time.”

This time the offer came and he accepted.

Visionary Changes

As one of the smallest (in terms of membership) of the 24 primary specialty societies, Dr. Nielsen said he is proud of the range of services the AAO-HNS provides.

“We do it all—practice management, IT, health policy, state and federal regulatory and legislative affairs, research, education, and the best meeting in the world—and the cost of that is roughly the same as it is for other societies, but we have to spread that out over just 10,000 doctors,” he said. “We have learned to become more effective or efficient as a staff and we require and benefit from a much higher level of volunteerism from our members than many other societies. That’s been quite successful.”

Compared to 12 years ago, Dr. Nielsen said the Academy has doubled the amount of work it is doing, even though it has reduced staff levels from 87 to 64 people since 2002.

“We now have a department that combines research, quality and health policy, as well as an IT (now called Information and Knowledge Management) unit that was paired down by half, but is now much more effective and efficient offering support around various processes, including the new website and community portal,” he said. “Overall, we’re doing a lot of things that we couldn’t do 12 years ago and we are doing them with more efficiency.”

He also takes pride in the Academy’s increased visibility and voice.

“We’ve gone from being kind of invisible in certain conversations to being sought out,” he said. “Government agencies and other organizations want to hear our ideas about healthcare, delivery, and payment reform. The respect we are given, owing to the Academy’s involvement in issues and our evidence-based opinion, has gone up dramatically.”

Quality Is Job No. 1

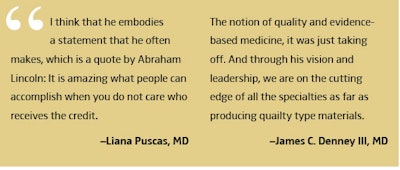

Nowhere can this increased visibility be seen more than in the area of quality and evidence-based guidelines, according to Dr. Nielsen. In the past decade, the AAO-HNS has become extremely skillful in addressing quality medicine in a formal way. The Academy has always had good doctors who care more about quality than about anything else, he said, but it never had a systematic, organized method of approaching or documenting the quality the specialty and its physicians offered.

When Dr. Nielsen took over in 2002, he mobilized the leaders of all the subspecialty societies in otolaryngology to develop evidence-based guidelines for the specialty that could take up the challenge issued by the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC).

“To have your guidelines published, they have to be of a certain rigor, meet a certain set of criteria; you can’t just make up a guideline and have the NGC publish it,” Dr. Nielsen said. “When we started this push, there were dozens and dozens of guidelines related to otolaryngology, and not a single one of them had been accepted by the NGC and none of them had been produced by the Academy.”

The AAO-HNSF has now produced more than a dozen NGC-published guidelines and has been cited by both the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies (CMSS) as an example of how best to produce effective and appropriate evidence-based standards.

The Academy has also diverted its resources to support more broadly based research, instead of focusing exclusively on the basic sciences and clinical translational research.

“We still maintain our support for those types of research, but we’ve expanded to health services research—focusing on how we get from the bedside into systems and populations so we can eliminate unwanted variations in healthcare and outcomes for the sake of improving public health.”

Dr. Nielsen said that with all of the changes taking place with regard to how healthcare is delivered, the Academy wants to make sure quality doesn’t suffer.

“There’s a real temptation for physicians and physician organizations to start checking boxes,” he said. “If we’re going to (offer care), we’re going to do it because it really makes patients better. We also want to aggregate the demand, because if we’ve set our standards so high that we exceeded everybody else’s, we are in pretty good shape.”

The Transition

When Dr. Nielsen turns his office over to the new EVP/CEO, James C. Denneny III, MD, on January 15, 2015, it will cap off a transition plan that has been in the works for more than year.

“I sat down with the executive leadership team a year ago to get processes in place and I told them my retirement could not be a distraction because we had too much work to do.”Dr. Nielsen said he started by having open conversations with senior leaders on staff to minimize any disruptions.

“I want my staff to feel secure and know they’re supported, because whatever we’ve changed, whatever we’ve accomplished, it isn’t me that’s accomplishing it,” Dr. Nielsen said. “It’s this incredible staff around me, and the thousands of doctors who make life-and-death decisions every single day and put in long hours and then, when they’re done, devote more time and energy and creativity and effort to the Academy. They give up their weekends and holidays with their families to do that. All we’ve accomplished has really been done by these people, and our success is really based on that.”

Dr. Nielsen said while it will be most important for the staff to help on board Dr. Denneny, he also outlined how he spends his days to give Denneny a sort of playbook to which he can refer. “I kept a log of how I spend my days—where I traveled, how I spent my days for the last year-and- a-half—and I’ll hand that off,” he said. “You can see my estimate of the hours that I spend on the College of Surgeons, the AMA, the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), the CMSS and all the other alphabet soup of meetings I attend.”

He also wrote his successor an executive summary of just what goes on at the Academy.

“I wrote it so he could read through it within 30 minutes and get a fair overview of what the Academy does,” he said.

“I want this to go so smoothly that next year at this time, people say, ‘Is he gone? I didn’t realize that,’” Dr. Nielsen said.

The Future

From here, Dr. Nielsen said he has a lot of options, but no formal plan in place.

“I’d like to serve a mission for the (Mormon) church with my wife, Rebecca,” Dr. Nielsen said. “And since all of our four children and 12 grandchildren have moved back to Arizona within 50 miles of each other, it’s time to get back there to see them.”

On the work front, Dr. Nielsen said it is too early to tell what he’s going to do next.

“Right now I have plenty of work to do for 2015,” he said. “I’ll be busy fulfilling obligations (to organizations such as PCPI and CMSS).”

But he does say this with certainty to the members, “I have spent more than a decade in your debt for the honor of being allowed to serve with our excellent staff and our outstanding specialty leaders. And between now and the end of the year, it will be time for me to perform the last responsibility of a leader—to say thank you.

“Thank you for your membership in the Academy. Thank you for your trust—in me, in your fellow Academy members, in your leaders, and in your staff. And most of all, thank you for your dedication to medicine and to your patients.”