Kids E.N.T. Health Month: Child Health Disparities

Emily F. Boss, MD, MPH Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Introduction: Focus on Health Disparities A health disparity may be defined as “an inequitable difference between groups in health, healthcare, and developmental outcomes that are potentially systematic and avoidable.” Every year in the United States, thousands of children experience disparities in healthcare access and utilization resulting in worse overall health status and outcomes. While many factors contribute to these disparities, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity are key influential social determinants. Disparities related to socioeconomic status include factors such as parental education, health literacy, insurance status, household income, access to transportation, and availability of social/familial support structures such as childcare. Disparities related to race and ethnicity may arise from cultural beliefs about disease and doctors, language differences, and historical discrimination. Provider factors may create further barriers to care of children, including issues with qualifications and experience with the care of medically complex children, or non-acceptance of certain insurance programs such as Medicaid. In general, children from low-income families and racial or ethnic minorities experience increased morbidity and disability compared to children who are white or more affluent. Moreover, parents of children from lower income environments are more likely to report poor communication with health providers. Case Studies in Pediatric Otolaryngology: Sleep and Hearing Because ear, nose, and throat conditions are so common in children, it is no surprise that a number of disease-specific disparities have been demonstrated in the care of children with otolaryngologic disease. One key example considers variation related to diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children. SDB affects 5 percent to 20 percent of U.S. children and occurs even more frequently in children with co-morbid conditions such as Trisomy 21 and obesity. Race and ethnicity may influence the risk of SDB in children. Indeed, SDB has been found to be more common in African-American children and Hispanic children compared with white children. Likewise, children in families of low socioeconomic status appear to be at increased risk for SDB. Some proposed explanations for these differences include factors such as household crowding in low-income homes, dietary influences, increased prevalence of obesity among certain racial and ethnic subgroups, higher exposure to secondhand smoke, or increased risk of upper respiratory infections. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of SDB in vulnerable children is extremely important, particularly with the increased risk for minority children to suffer comorbid conditions such as obesity, neurocognitive delays, and behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Although one might anticipate higher rates of adenotonsillectomy to treat SDB, which is often seen in at-risk or minority children, this trend has not been observed, perhaps because vulnerable subgroups of children may experience barriers to otolaryngic care, even with insurance coverage. Moreover, the wide variation in tonsillectomy rates across U.S. geographic regions calls into question the effects of differences in healthcare delivery systems and insurance plans across the country. Efforts to reduce disparities related to evaluation and treatment of pediatric SDB may potentially include standardization of clinical protocols across regions, expanded coverage and access for children with public or no insurance, and application of shared decision-making to reduce unwarranted variation and promote appropriate use of adenotonsillectomy. Health disparities are also evident for children with hearing loss, where hearing services are limited for children from racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic minorities. For example, proportionately higher rates of cochlear implantation are observed in children who live in areas with high median income and in children who are white or Asian compared to other minority counterparts. Children from low socioeconomic strata display poorer speech and language outcomes following implantation. Families of hearing-impaired children live closer to the poverty level and more frequently are insured by Medicaid. Additionally, low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for otitis media with effusion. Multiple barriers may contribute to these health disparities experienced by children with hearing loss, including communication hurdles, medical costs for diagnosis, medical visits for audiologic evaluation, fitting of hearing aids, care of associated external and middle ear problems, and costs of assistive devices. Both monetary costs and time commitments related to special education services, speech and language pathologists, and interpreters may also augment health disparities related to hearing loss. The Role of Access The presence of health insurance is a key factor for promotion of improved health status and access to routine healthcare. Children of racial minorities and children from low socioeconomic strata are more likely to experience reduced healthcare coverage and access to care. In 2011, about 16.1 million (22 percent) of U.S. children younger than 17 years old lived in poverty, 39 percent of children were covered by public health insurance, and 7 million children were uninsured. Hispanic children were less likely to have health insurance (85 percent insured) compared to non-Hispanic white (93 percent insured) or black (90 percent insured) children. Even when children do have health insurance coverage, true access may limit referrals to otolaryngologic care. Research on access to specialty care found that in one community 31 percent of patients with public insurance were not offered otolaryngology appointments, and for clinics that accepted all insurance types, children with public insurance waited on average 53 days for an appointment compared with an average of six days for privately-insured children. In another community, less than 20 percent of otolaryngologists were willing to perform tonsillectomy on children with publicly funded insurance due to administrative and financial burdens placed on their practices. Although the Affordable Care Act will expand Medicaid coverage for children, it remains to be seen whether improved access to otolaryngologic and other specialty care will follow. Working to Reduce Disparities Although tracking and establishing the variations in healthcare access and utilization across child subgroups in otolaryngology is important, reducing these disparities in care and improving outcomes for vulnerable children is a separate challenge. The Department of Health and Human Services “Healthy People” program has made reducing disparities and achieving health equity a major goal during the past two decades. Our specialty is charged with studying the unique characteristics of our specific patient population, our specialty disease patterns and variation, and local practice/health system limitations in order to best design strategies to promote equitable otolaryngic healthcare for children of all backgrounds. Some potentially fruitful interventions may include construction of innovative educational programs targeting rural and inner city pediatricians, which focus on common conditions such as SDB and hearing loss; creation of policies which improve reimbursement to otolaryngologists serving areas where access for at-risk children is limited; development of outreach programs initiated by larger health organizations to provide greater regional otolaryngic care; design of health educational materials which are applicable to parents of all levels of health literacy; and conception of formalized programs educating otolaryngology providers on use of culturally-competent communication strategies with patients. References and Resources: Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing Access to Specialty Care for Children with Public Insurance. N Engl J Med 2011; 265:2324-33. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Cheng TL, Dreyer BP, Jenkins RR. Introduction: Child health disparities and health literacy. Pediatrics 2009;124 Suppl 3:S161-S162. National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation. Reducing Health Disparities Among Children: Strategies and Programs for Health Plans. 2007. Boss EF, Smith DF, Ishman SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75:299-307. Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1527-1532. Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, Nelson L, Rosen CL, Drotar D, Redline S. Neighborhood disadvantage as a risk factor for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr 2006;149:342-347. Boss EF, Marsteller JA, Simon AE. Outpatient tonsillectomy in children: demographic and geographic variation in the United States, 2006. J Pediatr 2012;160:814-819. Wang EC, Choe MC, Meara JG, Koempel JA. Inequality of access to surgical specialty health care: why children with government-funded insurance have less access than those with private insurance in Southern California. Pediatrics 2004;114:e584-e590. Stern RE, Yueh B, Lewis C, Norton S, Sie KC. Recent epidemiology of pediatric cochlear implantation in the United States: disparity among children of different ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Laryngoscope 2005;115:125-131. Kirkham E, Sacks C, Baroody F, Siddique J, Nevins ME, Woolley A, Suskind D. Health disparities in pediatric cochlear implantation: an audiologic perspective. Ear Hear 2009;30:515-525. Boss EF, Niparko JK, Gaskin DJ, Levinson KL. Socioeconomic disparities for hearing-impaired children in the United States. Laryngoscope 2011;121:860-866.

Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Introduction: Focus on Health Disparities

A health disparity may be defined as “an inequitable difference between groups in health, healthcare, and developmental outcomes that are potentially systematic and avoidable.” Every year in the United States, thousands of children experience disparities in healthcare access and utilization resulting in worse overall health status and outcomes. While many factors contribute to these disparities, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity are key influential social determinants. Disparities related to socioeconomic status include factors such as parental education, health literacy, insurance status, household income, access to transportation, and availability of social/familial support structures such as childcare. Disparities related to race and ethnicity may arise from cultural beliefs about disease and doctors, language differences, and historical discrimination. Provider factors may create further barriers to care of children, including issues with qualifications and experience with the care of medically complex children, or non-acceptance of certain insurance programs such as Medicaid. In general, children from low-income families and racial or ethnic minorities experience increased morbidity and disability compared to children who are white or more affluent. Moreover, parents of children from lower income environments are more likely to report poor communication with health providers.

Case Studies in Pediatric Otolaryngology: Sleep and Hearing

Because ear, nose, and throat conditions are so common in children, it is no surprise that a number of disease-specific disparities have been demonstrated in the care of children with otolaryngologic disease. One key example considers variation related to diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children. SDB affects 5 percent to 20 percent of U.S. children and occurs even more frequently in children with co-morbid conditions such as Trisomy 21 and obesity. Race and ethnicity may influence the risk of SDB in children. Indeed, SDB has been found to be more common in African-American children and Hispanic children compared with white children. Likewise, children in families of low socioeconomic status appear to be at increased risk for SDB. Some proposed explanations for these differences include factors such as household crowding in low-income homes, dietary influences, increased prevalence of obesity among certain racial and ethnic subgroups, higher exposure to secondhand smoke, or increased risk of upper respiratory infections.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment of SDB in vulnerable children is extremely important, particularly with the increased risk for minority children to suffer comorbid conditions such as obesity, neurocognitive delays, and behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Although one might anticipate higher rates of adenotonsillectomy to treat SDB, which is often seen in at-risk or minority children, this trend has not been observed, perhaps because vulnerable subgroups of children may experience barriers to otolaryngic care, even with insurance coverage. Moreover, the wide variation in tonsillectomy rates across U.S. geographic regions calls into question the effects of differences in healthcare delivery systems and insurance plans across the country. Efforts to reduce disparities related to evaluation and treatment of pediatric SDB may potentially include standardization of clinical protocols across regions, expanded coverage and access for children with public or no insurance, and application of shared decision-making to reduce unwarranted variation and promote appropriate use of adenotonsillectomy.

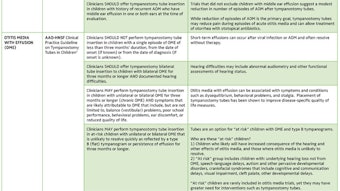

Health disparities are also evident for children with hearing loss, where hearing services are limited for children from racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic minorities. For example, proportionately higher rates of cochlear implantation are observed in children who live in areas with high median income and in children who are white or Asian compared to other minority counterparts. Children from low socioeconomic strata display poorer speech and language outcomes following implantation. Families of hearing-impaired children live closer to the poverty level and more frequently are insured by Medicaid. Additionally, low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for otitis media with effusion. Multiple barriers may contribute to these health disparities experienced by children with hearing loss, including communication hurdles, medical costs for diagnosis, medical visits for audiologic evaluation, fitting of hearing aids, care of associated external and middle ear problems, and costs of assistive devices. Both monetary costs and time commitments related to special education services, speech and language pathologists, and interpreters may also augment health disparities related to hearing loss.

The Role of Access

The presence of health insurance is a key factor for promotion of improved health status and access to routine healthcare. Children of racial minorities and children from low socioeconomic strata are more likely to experience reduced healthcare coverage and access to care. In 2011, about 16.1 million (22 percent) of U.S. children younger than 17 years old lived in poverty, 39 percent of children were covered by public health insurance, and 7 million children were uninsured. Hispanic children were less likely to have health insurance (85 percent insured) compared to non-Hispanic white (93 percent insured) or black (90 percent insured) children. Even when children do have health insurance coverage, true access may limit referrals to otolaryngologic care. Research on access to specialty care found that in one community 31 percent of patients with public insurance were not offered otolaryngology appointments, and for clinics that accepted all insurance types, children with public insurance waited on average 53 days for an appointment compared with an average of six days for privately-insured children. In another community, less than 20 percent of otolaryngologists were willing to perform tonsillectomy on children with publicly funded insurance due to administrative and financial burdens placed on their practices. Although the Affordable Care Act will expand Medicaid coverage for children, it remains to be seen whether improved access to otolaryngologic and other specialty care will follow.

Working to Reduce Disparities

Although tracking and establishing the variations in healthcare access and utilization across child subgroups in otolaryngology is important, reducing these disparities in care and improving outcomes for vulnerable children is a separate challenge. The Department of Health and Human Services “Healthy People” program has made reducing disparities and achieving health equity a major goal during the past two decades. Our specialty is charged with studying the unique characteristics of our specific patient population, our specialty disease patterns and variation, and local practice/health system limitations in order to best design strategies to promote equitable otolaryngic healthcare for children of all backgrounds. Some potentially fruitful interventions may include construction of innovative educational programs targeting rural and inner city pediatricians, which focus on common conditions such as SDB and hearing loss; creation of policies which improve reimbursement to otolaryngologists serving areas where access for at-risk children is limited; development of outreach programs initiated by larger health organizations to provide greater regional otolaryngic care; design of health educational materials which are applicable to parents of all levels of health literacy; and conception of formalized programs educating otolaryngology providers on use of culturally-competent communication strategies with patients.

References and Resources:

Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing Access to Specialty Care for Children with Public Insurance. N Engl J Med 2011; 265:2324-33.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Cheng TL, Dreyer BP, Jenkins RR. Introduction: Child health disparities and health literacy. Pediatrics 2009;124 Suppl 3:S161-S162.

National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation. Reducing Health Disparities Among Children: Strategies and Programs for Health Plans. 2007.

Boss EF, Smith DF, Ishman SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75:299-307.

Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1527-1532.

Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, Nelson L, Rosen CL, Drotar D, Redline S. Neighborhood disadvantage as a risk factor for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr 2006;149:342-347.

Boss EF, Marsteller JA, Simon AE. Outpatient tonsillectomy in children: demographic and geographic variation in the United States, 2006. J Pediatr 2012;160:814-819.

Wang EC, Choe MC, Meara JG, Koempel JA. Inequality of access to surgical specialty health care: why children with government-funded insurance have less access than those with private insurance in Southern California. Pediatrics 2004;114:e584-e590.

Stern RE, Yueh B, Lewis C, Norton S, Sie KC. Recent epidemiology of pediatric cochlear implantation in the United States: disparity among children of different ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Laryngoscope 2005;115:125-131.

Kirkham E, Sacks C, Baroody F, Siddique J, Nevins ME, Woolley A, Suskind D. Health disparities in pediatric cochlear implantation: an audiologic perspective. Ear Hear 2009;30:515-525.

Boss EF, Niparko JK, Gaskin DJ, Levinson KL. Socioeconomic disparities for hearing-impaired children in the United States. Laryngoscope 2011;121:860-866.