Clinical Practice Guideline: Acute Otitis Externa

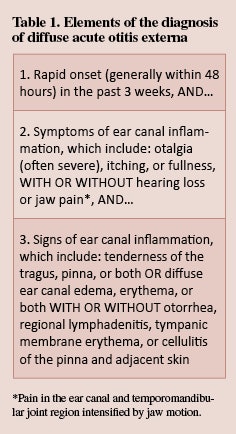

Executive Summary Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH; Seth R. Schwartz, MD, MPH; C. Ron Cannon, MD; Peter S. Roland, MD; Geoffrey R. Simon, MD; Kaparaboyna Ashok Kumar, MD, FRCS, FAAFP; William W. Huang, MD, MPH; Helen W. Haskell, MA; Peter J. Robertson, MPA. Corresponding author: Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, Department of Otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center and Long Island College Hospital, 339 Hicks Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201-5514. Email: richrosenfeld@msn.com. This month, the AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) published its first clinical practice guideline update, “Acute Otitis Externa,” as a supplement to Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Recommendations developed address appropriate diagnosis of acute otitis externa (AOE) and the use of oral and topical antimicrobials and highlight the need for adequate pain relief. The guideline was developed using the a priori protocol for guideline updates outlined in the AAO-HNS Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual.1 The complete guideline is available at http://oto.sagepub.com. To assist in implementing the guideline recommendations, this article summarizes the rationale, purpose, and key action statements. Recommendations in a guideline can be implemented only if they are clear and identifiable. This goal is best achieved by structuring the guideline around a series of key action statements, which are supported by amplifying text and action statement profiles. For ease of reference, only the statements and profiles are included in this brief summary. Please refer to the complete guideline for the important information in the amplifying text that further explains the supporting evidence and details of implementation for each key action statement. For more information about the AAO-HNSF’s other quality knowledge products (clinical practice guidelines and clinical consensus statements), our guideline development methodology, or to submit a topic for future guideline development, please visit http://www.entnet.org/guidelines. Differences from Prior Guideline This clinical practice guideline is an update and replacement for an earlier guideline published in 2006 by the AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.1 Changes in content and methodology from the prior guideline include: Addition of a dermatologist and consumer advocate to the guideline development group Expanded action statement profiles to explicitly state confidence in the evidence, intentional vagueness, and differences of opinion Enhanced external review process to include public comment and journal peer review New evidence from 12 randomized, controlled trials and two systematic reviews Review and update of all supporting text Emphasis on patient education and counseling with new tables that list common questions with clear, simple answers and provide instructions for properly administering ear drops Introduction Acute otitis externa (AOE) as discussed in this guideline is defined as diffuse inflammation of the external ear canal, which may also involve the pinna or tympanic membrane. A diagnosis of diffuse AOE requires rapid onset (generally within 48 hours) in the past three weeks of symptoms and signs of ear canal inflammation as detailed above in Table 1. A hallmark sign of diffuse AOE is tenderness of the tragus, pinna, or both that is often intense and disproportionate to what might be expected based on visual inspection. AOE is a cellulitis of the ear canal skin and subdermis, with acute inflammation and variable edema. Nearly all (98 percent) AOE in North America is bacterial.2 The most common pathogens are Pseudomonas aeruginosa (20-60 percent prevalence) and Staphylococcus aureus (10-70 percent prevalence), often occurring as a polymicrobial infection. Other pathogens are principally Gram negative organisms (other than P. aeruginosa), any one of which cause no more than 2-3 percent of cases in large clinical series.3-10 Fungal involvement is distinctly uncommon in primary AOE, but may be more common in chronic otitis externa or after treatment of AOE with topical, or less often systemic, antibiotics.11 The primary outcome considered in this guideline is clinical resolution of AOE, which implies resolution of all presenting signs and symptoms (e.g., pain, fever, otorrhea). Additional outcomes considered include minimizing the use of ineffective treatments; eradicating pathogens; minimizing recurrence, cost, complications, and adverse events; maximizing the health-related quality of life of individuals afflicted with AOE; increasing patient satisfaction;40 and permitting the continued use of necessary hearing aids. The relatively high incidence of AOE and the diversity of interventions in practice make AOE an important condition for the use of an up-to-date, evidence-based practice guideline. Purpose The primary purpose of the original guideline was to promote appropriate use of oral and topical antimicrobials for AOE and to highlight the need for adequate pain relief. An updated guideline is needed because of new clinical trials, new systematic reviews, and the lack of consumer participation in the initial guideline development group. The target patient is aged 2 years or older with diffuse AOE, defined as generalized inflammation of the external ear canal, with or without involvement of the pinna or tympanic membrane. This guideline does not apply to children younger than 2 years or to patients of any age with chronic or malignant (progressive necrotizing) otitis externa. AOE is uncommon before age 2 years, and very limited evidence exists regarding treatment or outcomes in this age group.41 Although the differential diagnosis of the “draining ear” will be discussed, recommendations for management will be limited to diffuse AOE, which is almost exclusively a bacterial infection. The following conditions will be briefly discussed, but not considered in detail: furunculosis (localized AOE), otomycosis, herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), and contact dermatitis. The guideline is intended for primary care and specialist clinicians, including otolaryngologists-head and neck surgeons, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency physicians, internists, nurse-practitioners, and physician assistants. The guideline is applicable to any setting in which children, adolescents, or adults with diffuse AOE would be identified, monitored, or managed. Key Action Statements STATEMENT 1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: Clinicians should distinguish diffuse AOE from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation of the external ear canal. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies and Grade D, reasoning from first principles Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Improved diagnostic accuracy Risks, harms, costs: None in following the recommended action Benefits-harm assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Importance of accurate diagnosis Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None, regarding the need for a proper diagnosis Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 2. MODIFYING FACTORS: Clinicians should assess the patient with diffuse AOE for factors that modify management (non-intact tympanic membrane, tympanostomy tube, diabetes, immunocompromised state, prior radiotherapy). Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Optimizing treatment of AOE through appropriate diagnosis and recognition of factors or co-morbid conditions that might alter management Risks, harms, costs: None from following the recommendation; additional expense of diagnostic tests or imaging studies to identify modifying factors Benefits-harm assessment: Preponderance of benefits over harm Value judgments: Avoiding complications that could potentially be prevented by modifying the management approach based on the specific factors identified Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 3. PAIN MANAGEMENT: The clinician should assess patients with AOE for pain and recommend analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain. Strong recommendation based on well-designed randomized trials with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, one randomized controlled trial limited to AOE; consistent, well-designed randomized trials of analgesics for pain relief in general Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Increase patient satisfaction, allow faster return to normal activities Risks, harms, costs: Adverse effects of analgesics; direct cost of medication Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Consensus among guideline development group that the severity of pain associated with AOE is under-recognized; preeminent role of pain relief as an outcome when managing AOE Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Moderate, choice of analgesic and degree of pain tolerance Exceptions: None Policy level: Strong recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 4. SYSTEMIC ANTIMICROBIALS: Clinicians should not prescribe systemic antimicrobials as initial therapy for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE unless there is extension outside the ear canal or the presence of specific host factors that would indicate a need for systemic therapy. Strong recommendation based on randomized controlled trials with minor limitations and a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, randomized controlled trials with minor limitations; no direct comparisons of topical vs. systemic therapy Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Avoid side effects from ineffective therapy, reduce antibiotic resistance by avoiding systemic antibiotics Risks, harms, costs: None Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Desire to decrease the use of ineffective treatments, societal benefit from avoiding the development of antibiotic resistance Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy level: Strong recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 5. TOPICAL THERAPY: Clinicians should prescribe topical preparations for initial therapy of diffuse, uncomplicated AOE. Recommendation based on randomized trials with some heterogeneity and a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials with significant limitations and heterogeneity Level of confidence in evidence: High for the efficacy of topical therapy as initial management, but low regarding comparative benefits of different classes of drugs or combinations of ototopical drugs Benefit: Effective therapy, low incidence of adverse events Risks, harms, costs: Direct cost of medication (varies greatly depending on drug class and selection), risk of secondary fungal infection (otomycosis) with prolonged use of topical antibiotics Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Randomized clinical trials results from largely specialty settings may not be generalizable to patients seen in primary care settings, where the ability to perform effective aural toilet may be limited Intentional vagueness: No specific recommendations regarding the choice of ototopical agent Role of patient preferences: Substantial role for patient preference in choice of topical therapeutic agent Exceptions: Patients with a non-intact tympanic membrane (see Statement No. 7, Non-intact tympanic membrane) Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 6. DRUG DELIVERY: The clinician should enhance the delivery of topical drops by informing the patient how to administer topical drops and by performing aural toilet, placing a wick, or both, when the ear canal is obstructed. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies and Grade D, first principles Level of confidence in evidence: High Benefit: Improved adherence to therapy and drug delivery Risks, harms, costs: Pain and local trauma caused by inappropriate aural toilet or wick insertion; direct cost of wick (inexpensive) Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Despite an absence of RCTs demonstrating a benefit of aural toilet, the guideline development group agreed that cleaning was appropriate, when necessary, to improve penetration of the drops into the ear canal Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: Choice of self-administering drops vs. using assistant Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 7. NON-INTACT TYMPANIC MEMBRANE: When the patient has a known or suspected perforation of the tympanic membrane, including a tympanostomy tube, the clinician should prescribe a non-ototoxic topical preparation. Recommendation based on reasoning from first principles and on exceptional circumstances where validating studies cannot be performed with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade D, reasoning from first principles, and Grade X, exceptional situations where validating studies cannot be performed Level of confidence in evidence: Moderate, because of extrapolation of data from animal studies and little direct evidence in patients with AOE Benefit: Reduce the possibility of hearing loss and balance disturbance Risk, harm, cost: Eardrops without ototoxicity may be more costly Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: Importance of avoiding iatrogenic hearing loss from a potentially ototoxic topical preparation when non-ototoxic alternatives are available; placing safety above direct cost Intentional vagueness: None Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None STATEMENT 8. OUTCOME ASSESSMENT: The clinician should reassess the patient who fails to respond to the initial therapeutic option within 48-72 hours to confirm the diagnosis of diffuse AOE and to exclude other causes of illness. Recommendation based on observational studies and a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, outcomes from individual treatment arms of randomized controlled trials of efficacy of topical therapy for AOE Level of confidence in evidence: Medium, because most randomized trials have been conducted in specialist settings and the generalizability to primary care settings is unknown Benefit: Identify misdiagnosis and potential complications from delayed management; reduce pain Risks, harms, costs: Cost of reevaluation by clinician Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm Value judgments: None Intentional vagueness: Time frame of 48 to 72 hours is specified since there are no data to substantiate a more precise estimate of time to improvement Role of patient preferences: None Exceptions: None Policy level: Recommendation Differences of opinion: None Disclaimer This clinical practice guideline is provided for information and education purposes only. It is not intended as a sole source of guidance in managing patients with acute otitis externa. Rather, it is designed to assist clinicians by providing an evidence-based framework for decision-making strategies. This guideline is not intended to replace clinical judgment or establish a protocol for all individuals with this condition and may not provide the only appropriate approach to diagnosis and management. As medical knowledge expands and technology advances, clinical indicators and guidelines are promoted as conditional and provisional proposals of what is recommended under specific conditions, but they are not absolute. Guidelines are not mandates; these do not and should not purport to be a legal standard of care. The responsible physician, in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient, must determine the appropriate treatment. Adherence to these guidelines will not ensure successful patient outcomes in every situation. The AAO-HNS, Inc. emphasizes that these clinical guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper treatment decisions or methods of care, nor exclusive of other treatment decisions or methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the work of the original guideline development group: Lance Brown, MD, MPH; Rowena J. Dolor, MD, MHS; Theodore G. Ganiats, MD; S. Maureen Hannley, PhD; Phillip Kokemueller, MS, CAE; S. Michael Marcy, MD; Richard N. Shiffman, MD, MCIS; Sandra S. Stinnett, DrPH; David L. Witsell, MD, MHS Disclosures Competing interests: Kaparaboyna Ashok Kumar, consultant for SoutheastFetalAlcoholSpectrumDisordersTrainingCenter and faculty speaker for the National Procedures Institute Sponsorship: AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Funding source: AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation References 1. Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Apr 2006;134(4 Suppl):S4-23. 2. Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. Jul 2002;112 (7 Pt 1):1166-1177. 3. Dibb WL. Microbial aetiology of otitis externa. J Infect. May 1991;22(3):233-239. 4. Agius AM, Pickles JM, Burch KL. A prospective study of otitis externa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Apr 1992;17(2):150-154. 5.Cassisi N, Cohn A, Davidson T, Witten BR. Diffuse otitis externa: clinical and microbiologic findings in the course of a multicenter study on a new otic solution. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. May-Jun 1977;86(3 Pt 3 Suppl 39):1-16. 6. Clark WB, Brook I, Bianki D, Thompson DH. Microbiology of otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jan 1997;116(1):23-25. 7. Jones RN, Milazzo J, Seidlin M. Ofloxacin otic solution for treatment of otitis externa in children and adults. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Nov 1997;123 (11):1193-1200. 8. Pistorius B, Westburry K, Drehobl, et al. Prospective, randomized, comparative trial of ciprofloxacin otic drops, with or without hydrocortisone, vs. polymyxin B-neomycin-hydrocortisone otic suspension in the treatment of acute diffuse otitis externa. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1999;8:387-395. 9. Arshad M, Khan NU, Ali N, AfridiNM. Sensitivity and spectrum of bacterial isolates in infectious otitis externa. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. Mar 2004;14(3):146-149. 10. Manolidis S, Friedman R, Hannley M, et al. Comparative efficacy of aminoglycoside versus fluoroquinolone topical antibiotic drops. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2004;130(3 Suppl):S83-88. 11. Martin TJ, Kerschner JE, FlanaryVA. Fungal causes of otitis externa and tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Nov 2005;69(11):1503-1508. 12. Hajioff D. Otitis externa. Clin Evid. Dec 2004(12):755-763. 13. HalpernMT, Palmer CS, Seidlin M. Treatment patterns for otitis externa. J Am Board Fam Pract. Jan-Feb 1999;12(1):1-7. 14. McCoy SI, Zell ER, Besser RE. Antimicrobial prescribing for otitis externa in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. Feb 2004;23(2):181-183. 15. Levy SB. The Antibiotic Paradox. How the Misuse of Antibiotics Destroys Their Curative Powers. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing; 2002. 16. McCormick AW, Whitney CG, Farley MM, et al. Geographic diversity and temporal trends of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. Nat Med. Apr 2003;9(4):424-430. 17. Bassetti M, Merelli M, Temperoni C, Astilean A. New antibiotics for bad bugs: where are we? Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. Aug 28 2013;12(1):22. 18. Nussinovitch M, Rimon A, Volovitz B, Raveh E, Prais D, Amir J. Cotton-tip applicators as a leading cause of otitis externa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Apr 2004;68(4):433-435. 19. Goffin FB. pH and otitis externa. Arch Otolaryngol. Apr 1963;77:363-364. 20. Martinez Devesa P, Willis CM, Capper JW. External auditory canal pH in chronic otitis externa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Aug 2003;28(4):320-324. 21. Yelland M. Otitis externa in general practice. Med J Aust. Mar 2 1992;156(5):325-326, 330. 22. Blake P, Matthews R, Hornibrook J. When not to syringe an ear. N Z Med J. Nov 13 1998;111(1077):422-424. 23. Berry RG, CollymoreVA. Otitis externa and facial cellulitis from Oriental ear cleaners. West J Med. May 1993;158(5):536. 24. Brook I, Coolbaugh JC. Changes in the bacterial flora of the external ear canal from the wearing of occlusive equipment. Laryngoscope. Jul 1984;94(7):963-965. 25. Hirsch BE. Infections of the external ear. Am J Otolaryngol. May-Jun 1992;13(3):145-155. 26. Russell JD, Donnelly M, McShane DP, Alun-Jones T, Walsh M. What causes acute otitis externa? J Laryngol Otol. Oct 1993;107(10):898-901. 27. Hoadley AW, KnightDE. External otitis among swimmers and nonswimmers. Arch Environ Health. Sep 1975;30(9):445-448. 28. Calderon R, Mood EW. A epidemiological assessment of water quality and “swimmer’s ear.” Arch Environ Health. Sep-Oct 1982;37(5):300-305. 29. Hansen UD. Otitis externa among users of private swimming pools. Ugeskr Laeger. Jul 7 1997;159(28):4383-4388. 30. Moore JE, Heaney N, Millar BC, Crowe M, Elborn JS. Incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational and hydrotherapy pools. Commun Dis Public Health. Mar 2002;5(1):23-26. 31. Hajjartabar M. Poor-quality water in swimming pools associated with a substantial risk of otitis externa due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Water Sci Technol. 2004;50(1):63-67. 32. Stroman DW, Roland PS, Dohar J, Burt W. Microbiology of normal external auditory canal. Laryngoscope. Nov 2001;111(11 Pt 1):2054-2059. 33. Steuer MK, Hofstadter F, Probster L, Beuth J, Strutz J. Are ABH antigenic determinants on human outer ear canal epithelium responsible for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections? ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. May-Jun 1995;57(3):148-152. 34. Sundstrom J, Jacobson K, Munck-Wikland E, Ringertz S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in otitis externa. A particular variety of the bacteria? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Aug 1996;122(8):833-836. 35. Bojrab DI, Bruderly T, Abdulrazzak Y. Otitis externa. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Oct 1996;29(5):761-782. 36. Nichols AW. Nonorthopaedic problems in the aquatic athlete. Clin Sports Med. Apr 1999;18(2):395-411, viii. 37. Raymond L, Spaur WH, Thalmann ED. Prevention of divers’ ear. Br Med J. Jan 7 1978;1(6104):48. 38. Sander R. Otitis externa: a practical guide to treatment and prevention. Am Fam Physician. Mar 1 2001;63(5):927-936, 941-922. 39. Hannley MT, Denneny JC, 3rd, Holzer SS. Use of ototopical antibiotics in treating 3 common ear diseases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jun 2000;122(6):934-940. 40. Shikiar R, HalpernMT, McGann M, Palmer CS, Seidlin M. The relation of patient satisfaction with treatment of otitis externa to clinical outcomes: development of an instrument. Clin Ther. Jun 1999;21(6):1091-1104. 41. Alter SJ, Vidwan NK, Sobande PO, Omoloja A, Bennett JS. Common childhood bacterial infections. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. Nov 2011;41(10):256-283.

Executive Summary

Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH; Seth R. Schwartz, MD, MPH; C. Ron Cannon, MD; Peter S. Roland, MD; Geoffrey R. Simon, MD; Kaparaboyna Ashok Kumar, MD, FRCS, FAAFP; William W. Huang, MD, MPH; Helen W. Haskell, MA; Peter J. Robertson, MPA. Corresponding author: Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, Department of Otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center and Long Island College Hospital, 339 Hicks Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201-5514. Email: richrosenfeld@msn.com.

To assist in implementing the guideline recommendations, this article summarizes the rationale, purpose, and key action statements. Recommendations in a guideline can be implemented only if they are clear and identifiable. This goal is best achieved by structuring the guideline around a series of key action statements, which are supported by amplifying text and action statement profiles. For ease of reference, only the statements and profiles are included in this brief summary. Please refer to the complete guideline for the important information in the amplifying text that further explains the supporting evidence and details of implementation for each key action statement.

For more information about the AAO-HNSF’s other quality knowledge products (clinical practice guidelines and clinical consensus statements), our guideline development methodology, or to submit a topic for future guideline development, please visit http://www.entnet.org/guidelines.

Differences from Prior Guideline

This clinical practice guideline is an update and replacement for an earlier guideline published in 2006 by the AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.1 Changes in content and methodology from the prior guideline include:

- Addition of a dermatologist and consumer advocate to the guideline development group

- Expanded action statement profiles to explicitly state confidence in the evidence, intentional vagueness, and differences of opinion

- Enhanced external review process to include public comment and journal peer review

- New evidence from 12 randomized, controlled trials and two systematic reviews

- Review and update of all supporting text

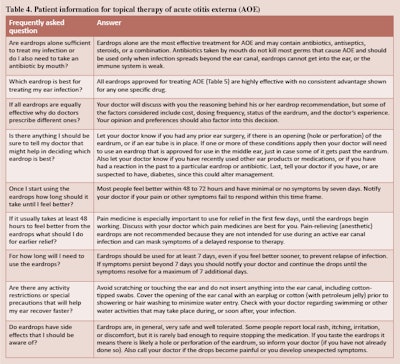

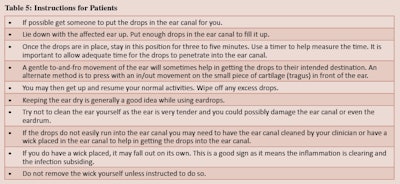

- Emphasis on patient education and counseling with new tables that list common questions with clear, simple answers and provide instructions for properly administering ear drops

Introduction

AOE is a cellulitis of the ear canal skin and subdermis, with acute inflammation and variable edema. Nearly all (98 percent) AOE in North America is bacterial.2 The most common pathogens are Pseudomonas aeruginosa (20-60 percent prevalence) and Staphylococcus aureus (10-70 percent prevalence), often occurring as a polymicrobial infection. Other pathogens are principally Gram negative organisms (other than P. aeruginosa), any one of which cause no more than 2-3 percent of cases in large clinical series.3-10 Fungal involvement is distinctly uncommon in primary AOE, but may be more common in chronic otitis externa or after treatment of AOE with topical, or less often systemic, antibiotics.11

The primary outcome considered in this guideline is clinical resolution of AOE, which implies resolution of all presenting signs and symptoms (e.g., pain, fever, otorrhea). Additional outcomes considered include minimizing the use of ineffective treatments; eradicating pathogens; minimizing recurrence, cost, complications, and adverse events; maximizing the health-related quality of life of individuals afflicted with AOE; increasing patient satisfaction;40 and permitting the continued use of necessary hearing aids. The relatively high incidence of AOE and the diversity of interventions in practice make AOE an important condition for the use of an up-to-date, evidence-based practice guideline.

Purpose

The guideline is intended for primary care and specialist clinicians, including otolaryngologists-head and neck surgeons, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency physicians, internists, nurse-practitioners, and physician assistants. The guideline is applicable to any setting in which children, adolescents, or adults with diffuse AOE would be identified, monitored, or managed.

Key Action Statements

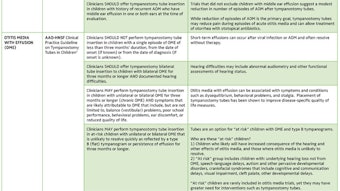

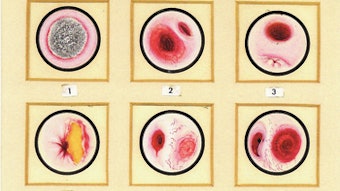

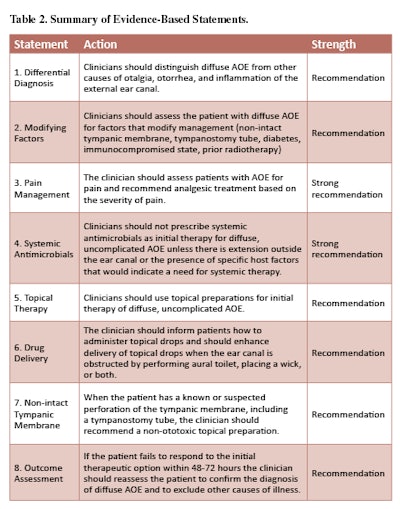

STATEMENT 1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS:

Clinicians should distinguish diffuse AOE from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation of the external ear canal. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies and Grade D, reasoning from first principles

- Level of confidence in evidence: High

- Benefit: Improved diagnostic accuracy

- Risks, harms, costs: None in following the recommended action

- Benefits-harm assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Importance of accurate diagnosis

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: None, regarding the need for a proper diagnosis

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 2. MODIFYING FACTORS:

Clinicians should assess the patient with diffuse AOE for factors that modify management (non-intact tympanic membrane, tympanostomy tube, diabetes, immunocompromised state, prior radiotherapy). Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies

- Level of confidence in evidence: High

- Benefit: Optimizing treatment of AOE through appropriate diagnosis and recognition of factors or co-morbid conditions that might alter management

- Risks, harms, costs: None from following the recommendation; additional expense of diagnostic tests or imaging studies to identify modifying factors

- Benefits-harm assessment: Preponderance of benefits over harm

- Value judgments: Avoiding complications that could potentially be prevented by modifying the management approach based on the specific factors identified

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: None

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 3. PAIN MANAGEMENT:

The clinician should assess patients with AOE for pain and recommend analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain. Strong recommendation based on well-designed randomized trials with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, one randomized controlled trial limited to AOE; consistent, well-designed randomized trials of analgesics for pain relief in general

- Level of confidence in evidence: High

- Benefit: Increase patient satisfaction, allow faster return to normal activities

- Risks, harms, costs: Adverse effects of analgesics; direct cost of medication

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Consensus among guideline development group that the severity of pain associated with AOE is under-recognized; preeminent role of pain relief as an outcome when managing AOE

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: Moderate, choice of analgesic and degree of pain tolerance

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Strong recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 4. SYSTEMIC ANTIMICROBIALS:

Clinicians should not prescribe systemic antimicrobials as initial therapy for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE unless there is extension outside the ear canal or the presence of specific host factors that would indicate a need for systemic therapy. Strong recommendation based on randomized controlled trials with minor limitations and a preponderance of benefit over harm.

- Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, randomized controlled trials with minor limitations; no direct comparisons of topical vs. systemic therapy

- Level of confidence in evidence: High

- Benefit: Avoid side effects from ineffective therapy, reduce antibiotic resistance by avoiding systemic antibiotics

- Risks, harms, costs: None

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Desire to decrease the use of ineffective treatments, societal benefit from avoiding the development of antibiotic resistance

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: None

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Strong recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

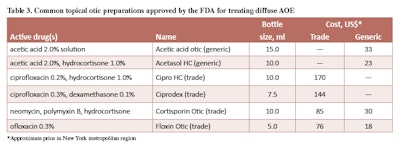

STATEMENT 5. TOPICAL THERAPY:

Clinicians should prescribe topical preparations for initial therapy of diffuse, uncomplicated AOE. Recommendation based on randomized trials with some heterogeneity and a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials with significant limitations and heterogeneity

- Level of confidence in evidence: High for the efficacy of topical therapy as initial management, but low regarding comparative benefits of different classes of drugs or combinations of ototopical drugs

- Benefit: Effective therapy, low incidence of adverse events

- Risks, harms, costs: Direct cost of medication (varies greatly depending on drug class and selection), risk of secondary fungal infection (otomycosis) with prolonged use of topical antibiotics

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Randomized clinical trials results from largely specialty settings may not be generalizable to patients seen in primary care settings, where the ability to perform effective aural toilet may be limited

- Intentional vagueness: No specific recommendations regarding the choice of ototopical agent

- Role of patient preferences: Substantial role for patient preference in choice of topical therapeutic agent

- Exceptions: Patients with a non-intact tympanic membrane (see Statement No. 7, Non-intact tympanic membrane)

- Policy level: Recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 6. DRUG DELIVERY:

The clinician should enhance the delivery of topical drops by informing the patient how to administer topical drops and by performing aural toilet, placing a wick, or both, when the ear canal is obstructed. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, observational studies and Grade D, first principles

- Level of confidence in evidence: High

- Benefit: Improved adherence to therapy and drug delivery

- Risks, harms, costs: Pain and local trauma caused by inappropriate aural toilet or wick insertion; direct cost of wick (inexpensive)

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Despite an absence of RCTs demonstrating a benefit of aural toilet, the guideline development group agreed that cleaning was appropriate, when necessary, to improve penetration of the drops into the ear canal

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: Choice of self-administering drops vs. using assistant

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 7. NON-INTACT TYMPANIC MEMBRANE:

When the patient has a known or suspected perforation of the tympanic membrane, including a tympanostomy tube, the clinician should prescribe a non-ototoxic topical preparation. Recommendation based on reasoning from first principles and on exceptional circumstances where validating studies cannot be performed with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade D, reasoning from first principles, and Grade X, exceptional situations where validating studies cannot be performed

- Level of confidence in evidence: Moderate, because of extrapolation of data from animal studies and little direct evidence in patients with AOE

- Benefit: Reduce the possibility of hearing loss and balance disturbance

- Risk, harm, cost: Eardrops without ototoxicity may be more costly

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: Importance of avoiding iatrogenic hearing loss from a potentially ototoxic topical preparation when non-ototoxic alternatives are available; placing safety above direct cost

- Intentional vagueness: None

- Role of patient preferences: None

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Recommendation

- Differences of opinion: None

STATEMENT 8. OUTCOME ASSESSMENT:

The clinician should reassess the patient who fails to respond to the initial therapeutic option within 48-72 hours to confirm the diagnosis of diffuse AOE and to exclude other causes of illness. Recommendation based on observational studies and a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate evidence quality: Grade C, outcomes from individual treatment arms of randomized controlled trials of efficacy of topical therapy for AOE

- Level of confidence in evidence: Medium, because most randomized trials have been conducted in specialist settings and the generalizability to primary care settings is unknown

- Benefit: Identify misdiagnosis and potential complications from delayed management; reduce pain

- Risks, harms, costs: Cost of reevaluation by clinician

- Benefits-harms assessment: Preponderance of benefit over harm

- Value judgments: None

- Intentional vagueness: Time frame of 48 to 72 hours is specified since there are no data to substantiate a more precise estimate of time to improvement

- Role of patient preferences: None

- Exceptions: None

- Policy level: Recommendation

Differences of opinion: None

Disclaimer

This clinical practice guideline is provided for information and education purposes only. It is not intended as a sole source of guidance in managing patients with acute otitis externa. Rather, it is designed to assist clinicians by providing an evidence-based framework for decision-making strategies. This guideline is not intended to replace clinical judgment or establish a protocol for all individuals with this condition and may not provide the only appropriate approach to diagnosis and management.

As medical knowledge expands and technology advances, clinical indicators and guidelines are promoted as conditional and provisional proposals of what is recommended under specific conditions, but they are not absolute. Guidelines are not mandates; these do not and should not purport to be a legal standard of care. The responsible physician, in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient, must determine the appropriate treatment. Adherence to these guidelines will not ensure successful patient outcomes in every situation. The AAO-HNS, Inc. emphasizes that these clinical guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper treatment decisions or methods of care, nor exclusive of other treatment decisions or methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the work of the original guideline development group: Lance Brown, MD, MPH; Rowena J. Dolor, MD, MHS; Theodore G. Ganiats, MD; S. Maureen Hannley, PhD; Phillip Kokemueller, MS, CAE; S. Michael Marcy, MD; Richard N. Shiffman, MD, MCIS; Sandra S. Stinnett, DrPH; David L. Witsell, MD, MHS

Disclosures

Competing interests: Kaparaboyna Ashok Kumar, consultant for SoutheastFetalAlcoholSpectrumDisordersTrainingCenter and faculty speaker for the National Procedures Institute

Sponsorship: AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation

Funding source: AmericanAcademy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation

References

1. Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Apr 2006;134(4 Suppl):S4-23.

2. Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. Jul 2002;112 (7 Pt 1):1166-1177.

3. Dibb WL. Microbial aetiology of otitis externa. J Infect. May 1991;22(3):233-239.

4. Agius AM, Pickles JM, Burch KL. A prospective study of otitis externa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Apr 1992;17(2):150-154.

5.Cassisi N, Cohn A, Davidson T, Witten BR. Diffuse otitis externa: clinical and microbiologic findings in the course of a multicenter study on a new otic solution. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. May-Jun 1977;86(3 Pt 3 Suppl 39):1-16.

6. Clark WB, Brook I, Bianki D, Thompson DH. Microbiology of otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jan 1997;116(1):23-25.

7. Jones RN, Milazzo J, Seidlin M. Ofloxacin otic solution for treatment of otitis externa in children and adults. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Nov 1997;123 (11):1193-1200.

8. Pistorius B, Westburry K, Drehobl, et al. Prospective, randomized, comparative trial of ciprofloxacin otic drops, with or without hydrocortisone, vs. polymyxin B-neomycin-hydrocortisone otic suspension in the treatment of acute diffuse otitis externa. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1999;8:387-395.

9. Arshad M, Khan NU, Ali N, AfridiNM. Sensitivity and spectrum of bacterial isolates in infectious otitis externa. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. Mar 2004;14(3):146-149.

10. Manolidis S, Friedman R, Hannley M, et al. Comparative efficacy of aminoglycoside versus fluoroquinolone topical antibiotic drops. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2004;130(3 Suppl):S83-88.

11. Martin TJ, Kerschner JE, FlanaryVA. Fungal causes of otitis externa and tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Nov 2005;69(11):1503-1508.

12. Hajioff D. Otitis externa. Clin Evid. Dec 2004(12):755-763.

13. HalpernMT, Palmer CS, Seidlin M. Treatment patterns for otitis externa. J Am Board Fam Pract. Jan-Feb 1999;12(1):1-7.

14. McCoy SI, Zell ER, Besser RE. Antimicrobial prescribing for otitis externa in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. Feb 2004;23(2):181-183.

15. Levy SB. The Antibiotic Paradox. How the Misuse of Antibiotics Destroys Their Curative Powers. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing; 2002.

16. McCormick AW, Whitney CG, Farley MM, et al. Geographic diversity and temporal trends of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. Nat Med. Apr 2003;9(4):424-430.

17. Bassetti M, Merelli M, Temperoni C, Astilean A. New antibiotics for bad bugs: where are we? Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. Aug 28 2013;12(1):22.

18. Nussinovitch M, Rimon A, Volovitz B, Raveh E, Prais D, Amir J. Cotton-tip applicators as a leading cause of otitis externa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Apr 2004;68(4):433-435.

19. Goffin FB. pH and otitis externa. Arch Otolaryngol. Apr 1963;77:363-364.

20. Martinez Devesa P, Willis CM, Capper JW. External auditory canal pH in chronic otitis externa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Aug 2003;28(4):320-324.

21. Yelland M. Otitis externa in general practice. Med J Aust. Mar 2 1992;156(5):325-326, 330.

22. Blake P, Matthews R, Hornibrook J. When not to syringe an ear. N Z Med J. Nov 13 1998;111(1077):422-424.

23. Berry RG, CollymoreVA. Otitis externa and facial cellulitis from Oriental ear cleaners. West J Med. May 1993;158(5):536.

24. Brook I, Coolbaugh JC. Changes in the bacterial flora of the external ear canal from the wearing of occlusive equipment. Laryngoscope. Jul 1984;94(7):963-965.

25. Hirsch BE. Infections of the external ear. Am J Otolaryngol. May-Jun 1992;13(3):145-155.

26. Russell JD, Donnelly M, McShane DP, Alun-Jones T, Walsh M. What causes acute otitis externa? J Laryngol Otol. Oct 1993;107(10):898-901.

27. Hoadley AW, KnightDE. External otitis among swimmers and nonswimmers. Arch Environ Health. Sep 1975;30(9):445-448.

28. Calderon R, Mood EW. A epidemiological assessment of water quality and “swimmer’s ear.” Arch Environ Health. Sep-Oct 1982;37(5):300-305.

29. Hansen UD. Otitis externa among users of private swimming pools. Ugeskr Laeger. Jul 7 1997;159(28):4383-4388.

30. Moore JE, Heaney N, Millar BC, Crowe M, Elborn JS. Incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational and hydrotherapy pools. Commun Dis Public Health. Mar 2002;5(1):23-26.

31. Hajjartabar M. Poor-quality water in swimming pools associated with a substantial risk of otitis externa due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Water Sci Technol. 2004;50(1):63-67.

32. Stroman DW, Roland PS, Dohar J, Burt W. Microbiology of normal external auditory canal. Laryngoscope. Nov 2001;111(11 Pt 1):2054-2059.

33. Steuer MK, Hofstadter F, Probster L, Beuth J, Strutz J. Are ABH antigenic determinants on human outer ear canal epithelium responsible for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections? ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. May-Jun 1995;57(3):148-152.

34. Sundstrom J, Jacobson K, Munck-Wikland E, Ringertz S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in otitis externa. A particular variety of the bacteria? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Aug 1996;122(8):833-836.

35. Bojrab DI, Bruderly T, Abdulrazzak Y. Otitis externa. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Oct 1996;29(5):761-782.

36. Nichols AW. Nonorthopaedic problems in the aquatic athlete. Clin Sports Med. Apr 1999;18(2):395-411, viii.

37. Raymond L, Spaur WH, Thalmann ED. Prevention of divers’ ear. Br Med J. Jan 7 1978;1(6104):48.

38. Sander R. Otitis externa: a practical guide to treatment and prevention. Am Fam Physician. Mar 1 2001;63(5):927-936, 941-922.

39. Hannley MT, Denneny JC, 3rd, Holzer SS. Use of ototopical antibiotics in treating 3 common ear diseases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jun 2000;122(6):934-940.

40. Shikiar R, HalpernMT, McGann M, Palmer CS, Seidlin M. The relation of patient satisfaction with treatment of otitis externa to clinical outcomes: development of an instrument. Clin Ther. Jun 1999;21(6):1091-1104.

41. Alter SJ, Vidwan NK, Sobande PO, Omoloja A, Bennett JS. Common childhood bacterial infections. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. Nov 2011;41(10):256-283.