Innovations in Pediatric Hearing Loss Management

Stay updated on groundbreaking innovations in pediatric hearing loss management from genetic testing to cochlear implants and emerging gene therapies.

Albert H. Park, MD, John A. Germiller, MD, PhD, Eliot Shearer, MD, PhD, and Kristan P. Alfonso, MD

Clinicians will learn:

- When to order genetic testing for a child with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL);

- How to diagnose and manage a child with congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV);

- Current indications for cochlear implantation (CI); and

- The current role of gene therapy.

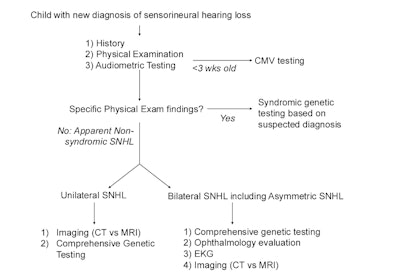

When to Order Genetic Testing for a Child with SNHL

It is recommended that all children with congenital SNHL should undergo genetic testing.1-3 Approximately 80% of congenital SNHL in the U.S. can be attributed to a genetic cause. Hearing loss gene panel testing uses massively parallel sequencing techniques that enable one to sequence hundreds of non-syndromic and syndromic hearing loss genes. The diagnostic yield of gene panels for pediatric hearing loss (i.e., the number of patients who receive a diagnosis after testing) is 43% overall, but ranges from 20%-60% depending on the patient phenotype.

Diagnostic yield is lower for those with asymmetric or unilateral SNHL, but those patients with these conditions are more likely to have a syndromic diagnosis. Diagnosis of a syndromic condition may facilitate identification of other abnormalities in the child. Comprehensive otolaryngologists should be able to order genetic testing, particularly given that most tests are now covered by insurance. Free, sponsored, gene panel testing for certain types of SNHL is also available.

How to Diagnose and Manage a Child with Congenital CMV

Congenital CMV is the most common cause of nongenetic SNHL. A urine CMV PCR for any infant who fails his or her newborn hearing screen is recommended before the infant is three weeks of age. An expanded targeted testing approach has been used in Utah since 2019. See Figure 4 in Suarez et al 2023.4

This approach is based on identifying a maternal history of CMV infection, microcephaly, small for gestational age, hepatosplenomegaly, petechial rash, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminases, failed newborn hearing screening or brain imaging abnormalities for testing. A multidisciplinary approach to this condition is recommended to include laboratory testing, brain imaging, early intervention services and diagnostic auditory brainstem response testing for surveillance and prognosis, and to determine whether antiviral therapy with valganciclovir is indicated.

Figure 1. Hearing Loss Diagnostic Evaluation

Figure 1. Hearing Loss Diagnostic Evaluation

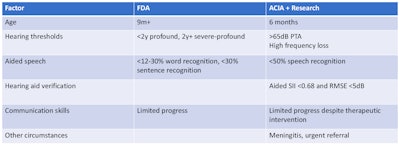

Current Indications for CI

Circumnavigating CI candidacy can be a challenge given the reality of health insurance coverage and outdated FDA approval policies. The expansion of FDA approval for pediatric CI first began in 1990 for 2-year-old children with bilateral profound SNHL. Since that time, unilateral profound SNHL was approved in 2019 for children 5 years of age or older and bilateral profound SNHL was approved in 2020 for infants nine months of age or older. Interestingly, there is no FDA approval for those with profound SNHL due to meningitis, with residual low frequency hearing, bilateral cochlear nerve deficiency, or for those with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Evidence-based practice is needed to guide clinical judgement.5,6 Early referral for CI consideration is recommended, informing and educating families and patients of candidacy, primary care providers and payors.

Table 1. Updated Indications for Cochlear Implantation Candidacy

The Current Role of Gene Therapy

There is increasing success in gene therapy for a wide range of genetic diseases (e.g., blindness, hemophilia, primary immune deficiency, and spinal muscle atrophy). The current focus has been on hearing loss restoration for those with preserved, healthy hair cells. The first candidate has been otoferlin (OTOF), a protein involved in priming, fusion, and replenishing of the synaptic vesicles in inner hair cells. OTOF-mediated hearing loss accounts for 1%-8% of all genetic SNHL. It causes severe to profound congenital deafness and is not treatable with hearing aids.7 The first child was treated in China in fall 2022. Nineteen children have undergone treatment since February 2024. All used a single-round window injection of AAV dual vector carrying a human OTOF transgene, a second detect (stapedotomy or canal fenestration) to facilitate perfusion and a transcanal or mastoidectomy/facial recess approach. Eighteen of 19 treated so far have experienced hearing improvement. Outcome in those with improvement has ranged from moderate aidable loss to mild loss with improvement over three to six months. Emerging data suggest lasting improvements for over one year. There have been no significant safety issues.

Notable Cases of Pediatric Hearing Loss Management

The panel reviewed several recent cases of pediatric hearing loss management that highlight notable challenges and barriers to timely, effective care.

A recent case involved an infant who failed her newborn hearing screen (NBHS) and lived 200 miles from a pediatric audiology center. Families with limited means and/or who live far from appropriate healthcare resources can face significant challenges in meeting and managing timely appointments.

Another case involved a 2-month-old infant who failed her NBHS and had bilateral serous otitis media. Timely diagnostic hearing testing and removal of the middle ear fluid is recommended if it does not resolve. A study by Huang et al. reported that 11.3% of infants with failed NBHS had permanent hearing loss.8 The placement of ventilation tubes by three months of age is recommended if the fluid does not resolve to permit timely natural sleep ABR testing.

The third case involved a 7-year-old child with late onset unilateral progressive SNHL. This child was found to have a TMPRSS3 pathogenic genetic variant which results in post-lingual progressive bilateral SNHL. This child’s hearing loss progressed to bilateral normal to profound SNHL; he ended up requiring bilateral cochlear implantation.

A final case involved a newborn with bilateral OTOF genetic variants as a cause of hearing loss. There can be a dilemma in recommending CI for a child who is not gaining access to sound, and the family wanting to wait for gene therapy.

There is general agreement that the field of pediatric hearing loss has never experienced such momentous changes as the past five years.

References

- Kim YS, Kim Y, Jeon HW, et al. Full etiologic spectrum of pediatric severe to profound hearing loss of consecutive 119 cases. Sci Rep. Jul 19 2022;12(1):12335. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16421-x

- Shearer AE, DeLuca AP, Hildebrand MS, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss using massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 7 2010;107(49):21104-9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012989107

- Shearer AE. Genetic testing for pediatric sensorineural hearing loss in the era of gene therapy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 1 2024;32(5):352-356. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000001005

- Suarez D, Nielson C, McVicar SB, et al. Analysis of an Expanded Targeted Early Cytomegalovirus Testing Program. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Sep 2023;169(3):679-686. doi:10.1002/ohn.320

- Park LR, Griffin AM, Sladen DP, Neumann S, Young NM. American Cochlear Implant Alliance Task Force Guidelines for Clinical Assessment and Management of Cochlear Implantation in Children With Single-Sided Deafness. Ear Hear. Mar/Apr 2022;43(2):255-267. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000001204

- Warner-Czyz AD, Roland JT, Jr., Thomas D, Uhler K, Zombek L. American Cochlear Implant Alliance Task Force Guidelines for Determining Cochlear Implant Candidacy in Children. Ear Hear. Mar/Apr 2022;43(2):268-282. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000001087

- Akil O, Dyka F, Calvet C, et al. Dual AAV-mediated gene therapy restores hearing in a DFNB9 mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Mar 5 2019;116(10):4496-4501. doi:10.1073/pnas.1817537116

- Huang EY, Suarez D, Holley A, et al. Hearing Outcomes in Failed Newborn Hearing Screening Infants With and Without Chronic Serous Otitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Sep 2023;169(3):687-693. doi:10.1002/ohn.306