The State of the Workforce: Pediatric Otolaryngology

Gain valuable insights from the recent Otolaryngology Workforce Report, including evolving trends, access disparities, and strategies to address future challenges.

Andrew J. Tompkins, MD, MBA, Chair of the AAO-HNS Workforce Task Force and Craig Derkay, MD, Chair of the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology (ASPO) Workforce & Compensation Committee

One of the rewarding things about working on a topic that touches everyone is interacting with and receiving feedback from stakeholders. We hope to incorporate your concerns and suggestions into future modules. Please keep your ideas coming and reach out to us at any time. Our Academy is the home to all otolaryngologists, regardless of subspecialty training or practice type. Case in point, in our last survey we had the opportunity to partner with the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology (ASPO) for a subspecialty focus. Fitting with this month’s Bulletin theme of pediatric otolaryngology, we’ll first highlight some important findings from this partnership and expand on other workforce topics in subsequent issues.

As a result of the partnership with ASPO, we were able to get buy-in and data sharing from all the fellowship training institutions. This process allowed us to compile a list of every pediatric otolaryngology fellow trained, dating back to program inceptions—including at some international and historical programs no longer training fellows. The subsequent deep dive into each of these trainees allowed for a geographic, practice type and active practice analysis. By gathering these data on each pediatric otolaryngologist, we were able to do a more thorough total workforce analysis and future projections.

We found training and longevity differences regarding pediatric otolaryngology and gender, which may have workforce implications. In the last eight years or so, a time when our residency trainees as a whole were majority male, we saw gender parity among pediatric otolaryngology fellowship graduates. This suggests an outsized interest in pediatric otolaryngology among our female trainees. Also notable were workforce longevity differences, where both male and female cohorts stayed in the workforce at roughly the same rate for about 25 years, after which female clinicians left the workforce earlier. More than anything, what this speaks to is the limitation of using otolaryngologists per 100,000 as a measurement for access. Both supply and demand factors are constantly changing, and we need more nuanced national and local data regarding wait time and distance analyses to describe patient access.

Although not all U.S. trainees eventually practice in the U.S., we still saw a more than two-fold increase in pediatric otolaryngologists establishing a U.S.-based practice per year over the last 20 years, which seems to have plateaued of late to around 38 U.S.-based practicing graduates per year. This increase has also coincided with a near 20% shift toward academic practices, which are largely urban when analyzed by office location access points (98.6%). What these trends suggest is a relative decline in geographic access for rural patients seeking pediatric otolaryngologic care.

Some states have no pediatric otolaryngologists, and a wide variation exists if looking at access on a per pediatric capita perspective by state. Different markets and states will warrant disparities on a per capita basis for multiple reasons, but what seems clear is that geographic access to pediatric subspecialty care is not universal. From a public health perspective, worsening rural access might be viewed as an acceptable trade-off if these practice shifts created improved wait times and/or heightened tertiary expertise. However, two data points speak to potential problems on these fronts as well.

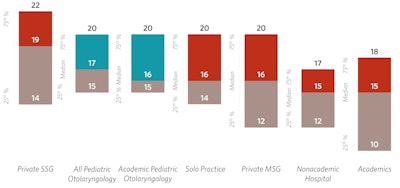

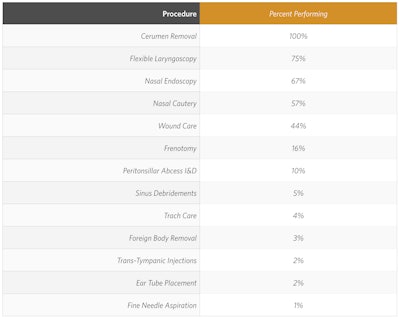

Wait time data from a national mystery caller paper2 recently revealed that pediatric otolaryngology wait times were the highest of any otolaryngology subspecialty—at least for the uncomplicated ear tube vignette used in this study. These June wait times for uncomplicated ear tubes were worse among academic settings, which is where pediatric otolaryngology work has been gravitating toward. Is this creating a dilutive effect on tertiary cases? Hiring advanced practice providers (APPs) may help address some appointment wait time bottlenecks, and APPs are both highly used and some of the most productive in pediatric otolaryngology settings.3 But unless those APPs are going to be doing in-office tubes to address the surgical bottleneck, which does not seem to be the case based on our survey findings,4 more subspecialized surgeons will seem to be required for uncomplicated cases such as these.

Table: Patients Seen by APPs Independently During Full Workday (Median, 25th/75th Percentile Shown)

Table: Procedures Performed by APPs

Workforce projections in our report highlight a second data point that may be cause for concern as it pertains to tertiary volumes. Each active and future U.S.-based pediatric otolaryngologist cohort was put on a more aggressive retirement glide path compared to historical norms. Further, the latest (2018) pediatric census projections were used to estimate pediatric population growth. These growth projections per year of around 140,000 do not speak to the realities of recent net pediatric population losses per year (approximately 130,000), given continued birth rate declines. The U.S.-based graduate numbers were held stable at 37 per year, compared with a recent mean of 38 per year. With these conservate projections, the pediatric otolaryngologist per 100,000 pediatric population will increase 30% by 2040. Will this growth, which seems to be gravitating toward academic, urban centers, affect tertiary case volumes?

These geographic access issues and workforce supply factor changes are not subtle and can have significant consequences for our patients. Leadership at the national and local level can help to study these issues as they take shape, mitigate potential downside effects, and seek to provide access where it is needed. On a policy front, we should study what systemic factors are producing access issues for our patients and seek to mitigate them through advocacy in partnership with other specialties whose patients may be facing similar challenges.

On the leadership front, ASPO has embarked on its once every 5 years' workforce and compensation survey to understand the pediatric otolaryngology market and some of its challenges since COVID-19. Under the leadership of David Chi, MD, and the ASPO Board of Directors, Craig Derkay, MD, is spearheading this effort. The 2025 survey will attempt to gather data from all practicing pediatric otolaryngologists (not just ASPO members) on a wide variety of topics affecting the specialty. These include questions regarding the role of APPs; plans for growth in established practices for adding MD/DOs and APPs; call burdens; access to OR and office care; recruitment and retention challenges; concerns with the practice window closing on the complex pediatric otolaryngology (CPO) exam; and the effect of the American College of Surgeons’ Children Surgical Verification Program on the specialty. As with prior surveys, this will help to establish means, medians and ranges for clinical and non-clinical compensation based on age, gender, geography and academic rank as well as starting salaries in the specialty for fellows entering the workforce. The goal is to gather the data for a presentation in May at the ASPO Business meeting.

All subspecialties have their unique challenges and opportunities and could benefit from an exploration of their workforces and what the future may hold. Our markets are nuanced and dynamic, which is why the task of describing and optimizing our workforce will be ongoing. We look forward to these ongoing and collaborative efforts so that we can provide the best access and skills to our patients.

References

- “Otolaryngology Workforce Report”, American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, accessed January 2, 2025, https://www.entnet.org/business-of-medicine/workforce-survey.

- Corbisiero MF, Muffly TM, Gottman DW, et al. Insurance Status and Access to Otolaryngology Care: National Mystery Caller Study in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024; 171(1): 98-108.

- Figure 12.16, Patients Seen by APPs Independently During Full Workday (Median, 25th/75th Percentile Shown), from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.

- Table 12.12, Procedures Performed by APPs, When Performing Procedures, from The 2023 Otolaryngology Workforce, published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2024.