Reg-ent Registry Insights: Exploring Trends in Age-Related Hearing Loss Treatment

The Reg-ent database offers valuable insights into the treatment of age-related hearing loss, uncovering key trends and treatment disparities.

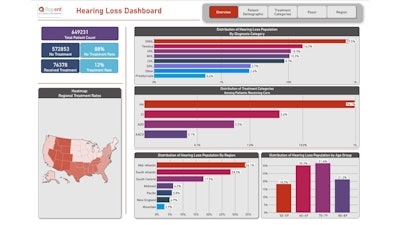

Over the past eight years, the Reg-ent clinical data registry has amassed data from 11 million patients across 50 million encounters. The Reg-ent team is using the curated dataset to assess research needs and to evaluate adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) published by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF). Reg-ent data can be analyzed longitudinally or provide a snapshot of current care practices. However, this merely scratches the surface of Reg-ent's potential.

Introduction

Hearing loss is a global public health problem affecting more than 466 million people worldwide, and it is expected to increase significantly with rising life expectancy.1 In the United States alone, an estimated 65.3% of adults who are 71 years and older, or approximately 21.5 million people, have at least some degree of hearing loss.1 Age is a significant risk factor for the development of hearing loss, making it one of the most common sensory disorders and the third most common chronic health condition among older adults.1 The AAO-HNSF recently published a CPG on age-related hearing loss (ARHL) with evidence-based recommendations for screening and managing ARHL in patients aged 50 and older. The CPG highlights the framework of ARHL as a gradual onset, chronic health condition.

Despite being the third most common physical condition after arthritis and heart disease in older adults, the relative percentage of patients receiving treatment remains low.2 Untreated ARHL is associated with various poor health outcomes including cognitive decline, medical adverse events, and social isolation, and remains a largely unaddressed, significant public health burden.2, 3 To explore this issue, we analyzed the Reg-ent database to analyze treatment and identify sociodemographic factors associated with lack of treatment, potentially highlighting disparities in hearing health care.

Materials and Methods

We queried the Reg-ent database for patients aged 50 and older who were diagnosed with hearing loss between 2019 and 2023. The patient data in Reg-ent relate to patients being seen by Reg-ent participants within the United States.

We derived the initial analytic cohort (“all hearing loss”) from Reg-ent's database and included patients aged 50 and older who had been diagnosed with hearing loss by a Reg-ent clinician based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9, ICD-10, and SNOMED diagnosis codes. Patients were grouped into 6 hearing loss categories: presbycusis (bilateral age-related hearing loss), sensorineural hearing loss (caused by damage to the inner ear or auditory nerve), conductive hearing loss, (caused by damage to the outer or middle ear, preventing sound waves from reaching the inner ear), idiopathic hearing loss, tinnitus, and mixed hearing loss. From the initial cohort, we identified a second cohort (“age-related hearing loss”) by narrowing the six initial hearing loss categories to include only the relevant categories of presbycusis and sensorineural hearing loss. For both cohorts, we analyzed the data to identify patients with documented treatment in their medical record.

For the initial cohort of all hearing loss patients, we assigned treatment categories using standardized coding (ICD-10, Current Procedural Terminology [CPT], and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes) and included hearing aids, cochlear implants, augmentative and alternative communication devices, and auditory osseointegrated devices. For the ARHL cohort, the assigned treatment categories focused on hearing aids and cochlear implants as these were two of the strongly recommended treatments referenced in the Key Action Statements within the ARHL CPG.

Results

Patient Population: All Hearing Loss Cohort

In the ‘all hearing loss’ cohort, there were 649,231 patients with hearing loss, 79.5% were diagnosed with SNHL, followed by tinnitus (16.3%), unspecified hearing loss (UHL) (10.9%), mixed hearing loss (MHL) (10.3%), conductive hearing loss (8.7%), and sudden idiopathic hearing loss (SIHL) (2.7%). Presbycusis accounted for only 0.6%. (Note: Total percentages throughout may exceed 100% as patients may have more than one hearing loss diagnosis or treatment.)

Abbreviations: SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; UHL, unspecified hearing loss; MHL, mixed hearing loss; CHL, conductive hearing loss; SIHL, sudden idiopathic hearing loss.

Abbreviations: SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; UHL, unspecified hearing loss; MHL, mixed hearing loss; CHL, conductive hearing loss; SIHL, sudden idiopathic hearing loss.

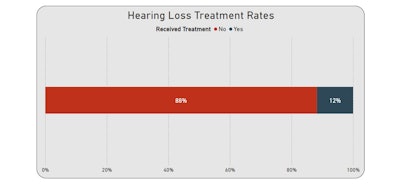

Treatment

Notably, 88% of patients had no documented treatment for hearing loss indicated in their record. Out of the 12% of patients with documented treatment, hearing aids were the predominant treatment among the subset of patients (96.1%), followed by cochlear implants (3.6%), auditory osseointegrated devices (0.5%), and augmentative and alternative communication devices (0.1%).

Demographic Analysis

Among female patients with hearing loss in the initial (all hearing loss) cohort, approximately 11% had documented treatment, with hearing aids as the most common indicated treatment (96.3% of treated patients) followed by cochlear implants (3.2%), auditory osseointegrated devices (0.5%), and alternative communication devices (0.1%). Among male patients in the initial (all hearing loss) cohort, 12% had treatment documented with hearing aids as the most common indicated treatment (95.3%) followed by cochlear implants (4.1%), auditory osseointegrated devices (0.5%), and augmentative and alternative communication devices (0.1%).

Patients in the initial (all hearing loss) cohort were categorized into three ethnic groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, and other ethnicities). Within the ethnic subgroups, 13% of the non-Hispanic population had treatment indicated compared to Hispanic patients at 10%, and patients from other ethnicities at 5%. Hearing aids were the most commonly indicated treatment across all groups (averaging approximately 95% for the three groups), while cochlear implants were only indicated in 4.3% of patients, on average, across the three groups.

Patients in the initial (all hearing loss) cohort were additionally categorized according to reported race. Our analysis revealed that indication of treatment was highest in patients categorized as White (14%), Asian (12%), Native Hawaiian (11%), other races (10%), and African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and multiracial (7% each). Hearing aids were the highest indicated treatment choice across all races, with an average of 94.6%. Patients categorized as multiracial were most likely to receive cochlear implants (11.5%) when compared with other groups.

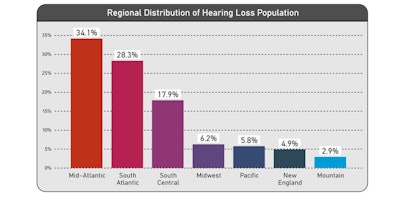

Regional Analysis

In our regional analysis of the 'all hearing loss cohort', the Mid-Atlantic region accounted for the highest distribution of hearing loss patients (34.1%), followed by the South Atlantic (28.3%), South Central (17.9%), Midwest (6.2%), Pacific (5.8%), New England (4.9%) and Mountain regions (2.9%).

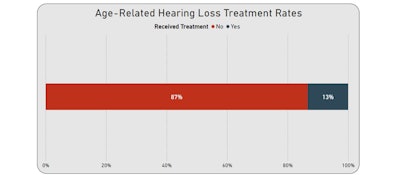

Patient Population: ARHL Cohort

In the ARHL cohort (517,532 patients), 13% had treatment indicated in their record. The age group 70–79 had the highest proportion of hearing loss (32.7%), followed by 60–69 years (29.6%), 80–89 years (22.5%), and 50–59 years (15.8%). These findings are consistent with the data provided in the CPG stating the prevalence of hearing loss doubles with each decade of life, affecting more than 60% of individuals by age 70 and 80% of individuals older than 85 years of age.1

Treatment

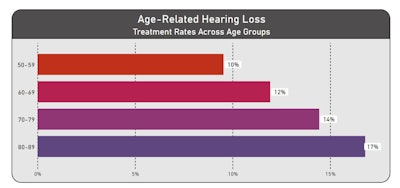

In terms of treatment for ARHL, patients in the 80–89-year age group displayed the highest documented treatment rate (17%), followed by 70–79 years (14%), 60–69 years (12%), and 50–59 years (10%). Hearing aids were the most indicated treatment across all age groups, with 96.4% of treated 60–69, 70–79, and 80–89-year-olds, on average, receiving hearing aids and 95.2% of treated 50–59-year olds receiving hearing aids. Cochlear implants were the second highest category treatment indicated in the ARHL cohort. Cochlear implants were more common in patients aged 50–59 years (4.8% of treated patients) while 60–69, 70–79, and 80–89-year-olds averaged approximately 3.6%.

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aids; CI, cochlear implants

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aids; CI, cochlear implants

Demographic Analysis

Among female patients with hearing loss in the ARHL cohort, approximately 13% had treatment documented, with hearing aids as the most common indicated treatment (96.7% of treated patients) followed by cochlear implants (3.3%). Among male patients in the ARHL cohort, 14% received treatment, with hearing aids as the most common indicated treatment (95.7%) followed by cochlear implants (4.3%).

Patients in the ARHL cohort were categorized into the same three ethnic groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, and other ethnicities) In the subgroups, 15% of the non-Hispanic population had treatment indicated compared to Hispanic patients at 11%, and patients from other ethnicities at 6%. Hearing aids were the most commonly indicated treatment across all groups (on average, 95.3% for each of the three groups), while cochlear implants were only indicated in 4.7% of patients, on average, across the three groups.

Patients in the ARHL cohort were additionally categorized according to reported race. Our analysis revealed that indication of treatment was highest in patients categorized as White (15%), Asian (13%), Native Hawaiian (or other Pacific Islander (12%), other races (11%), and African American and American Indian or Alaskan Native (9%), and multiracial (7%). Hearing aids were the highest indicated treatment received across all racial groups, with an average of 94.8%. Patients categorized as multiracial were most likely to receive cochlear implants (13.6) when compared with other groups.

Discussion

The number of individuals with hearing loss conditions has been rising and is expected to increase significantly in coming years.1,3 The Reg-ent team conducted this analysis to begin understanding hearing health disparities, one of the important research gaps identified in the ARHL CPG.

Our analysis revealed that most patients with diagnosed hearing loss did not have a recorded treatment. Among those treated, hearing aids were the most common treatment for hearing loss across both cohorts and all patients. Well fitting hearing aids are an effective intervention and rehabilitation for patients with presbycusis.4 However, further research is necessary to determine the factors that affect the efficiency of hearing aids. Parameters such as fitting, compression, and speech reception threshold should be considered for the effective use of hearing aids.4

One possible explanation for the low treatment rates observed is a lack of insurance coverage and the high cost of hearing health care in the United States. Adjustment, fitting, and hearing tests may not be covered by a patient’s insurance, which could limit their access to hearing health care, including hearing aids, and could result in low utilization of hearing aids.

As recommended in the CPG, cochlear implants have been a standard treatment for severe to profound hearing loss for decades.1 Cochlear implants are often recommended as a treatment plan when hearing loss is significant and/or when hearing aids are unable to provide adequate rehabilitation. Cochlear Implants have proven to be safe and effective in improving a patient’s ability to communicate and have been shown to improve hearing-related quality of life for appropriately selected candidates in several clinical trials.1 Despite the efficacy rate, their estimated use across patients diagnosed with hearing loss is only 5%–12.7%.1 This significant underutilization may result from patients’ unawareness of their eligibility for the treatment combined with inadequate patient compliance and/or social stigma around utilizing a hearing device.

Limitations affecting the results of this analysis include the inability to capture patients’ use of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids and other OTC assistive listening devices not recorded in medical records. The data were also restricted to practices participating in Reg-ent. More extensive studies are warranted to investigate disparities in hearing loss treatment and potential barriers affecting treatment rates.

Conclusion

The negative health impact and social outcomes associated with untreated age-related hearing loss warrant urgent action to improve access to hearing health care while reducing sociodemographic and socioeconomic barriers.2 Improving access to hearing screening, decreasing the costs of hearing healthcare for patients, and increasing treatment availability are all crucial steps that will bring us closer to optimizing hearing healthcare, particularly for older patients.

Share Your Ideas for Research Using Reg-ent

This article merely touches on the vast potential of Reg-ent data. If you are a current Reg-ent participant or involved in an AAO-HNS/F committee-sponsored research project, submit data requests by visiting the Reg-ent Research webpage.

Stay tuned for our next installment of Reg-ent Registry Insights as we look into Key Action Statements from the upcoming guidelines in development.

References

- Tsai Do BS, Bush ML, Weinreich HM, Schwartz SR, Anne S, Adunka OF, Bender K, Bold KM, Brenner MJ, Hashmi AZ, Keenan TA, Kim AH, Moore DJ, Nieman CL, Palmer CV, Ross EJ, Steenerson KK, Zhan KY, Reyes J, Dhepyasuwan N. Clinical Practice Guideline: Age-Related Hearing Loss.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024 May;170 Suppl 2:S1-S54. doi: 10.1002/ohn.750. PMID: 38687845.

- Catherine Palmer, Lori Zitelli, Barriers to Hearing Health Care for Aging Adults: Reframing the Conversation, Innovation in Aging, Volume 8, Issue 5, 2024, igae035, https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igae035

- Davis AC, Hoffman HJ. Hearing loss: rising prevalence and impact. Bull World Health Organ.2019; 97(10): 646-646A.

- Wu X, Ren Y, Wang Q, Li B, Wu H, Huang Z, Wang X. Factors associated with the efficiency of hearing aids for patients with age-related hearing loss. Clin Interv Aging. 2019 Feb 26;14:485-492. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S190651. PMID: 30880929; PMCID: PMC6396655.

Additional Resources

Reed NS, Garcia-Morales EE, Myers C, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss and hearing aid use among US Medicare beneficiaries aged 71 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2023; 6(7):e2326320.

Humes LE. U.S. Population data on hearing loss, trouble hearing, and hearing-device use in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-12, 2015-16, and 2017-20. Trends Hear. 2023; 27:233121652311609.

Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008; 168(14): 1522-1530.

Huddle MG, Goman AM, Kernizan FC, et al. The Economic Impact of Adult Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017; 143(10): 1040-1048.

Wick CC, Kallogjeri D, McJunkin JL, et al. Hearing and quality-of-life outcomes after cochlear implantation in adult hearing aid users 65 years or older: a secondary analysis of a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 146(10): 925-932.

Nassiri AM, Sorkin DL, Carlson ML. Current estimates of cochlear implant utilization in the United States. Otol Neurotol. 2022; 43(5): e558-e562.