Take in the Sun and Simulation in Miami Beach

Simulation for surgical training dates to at least the 4th century BC, but the tools and techniques have advanced since then. Try out the latest in surgical simulation at #OTOMTG24.

Elliot Regenbogen, MD, on behalf of the General Otolaryngology and Sleep Education Committee

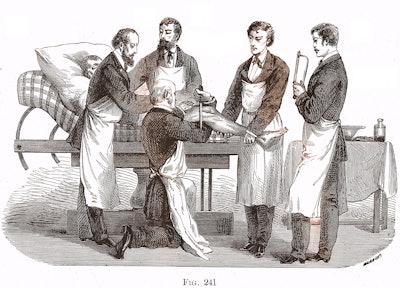

When Andreas Vesalius published the seminal De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543, he ushered in a renaissance of anatomical study in Europe along with an interest in three-dimensional models created in wood, ivory, bronze, and wax. Although cadaveric preservation techniques improved toward the end of the 17th century, the process was time-consuming and required technicians with a less available skill set. Models made of wax flourished up until the 19th century, along with plaster casts from frozen specimens, which were less expensive.4,5

The functional complexity of simulation trainers increased during the 18th to 20th centuries, initially driven by the adoption of obstetrics training models. The use of simulation for surgical training can be traced to Sushruta who lived in modern-day India between the 4th and 6th centuries BC. However, descriptions of the use of surgical simulators did not appear until the 19th century—initially for hernia repair and ophthalmic surgery.6,2

One of the earlier applications of simulation education in otolaryngology was at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in the 1890s. Laryngology was taught over 12 lessons in the Vanderbilt Clinic, during which students practiced on a ‘‘laryngoscopic phantom [made] by Bock of Leipzig…preliminary to the examination of the living subject.’’7 When German laryngologist Gustav Killian developed the direct bronchoscope for removal of foreign bodies in 1902, he also developed a bronchoscopy simulator for practice.8

The creation of the simple mannequin simulator “Resusci-Anne” in the 1960s marks the beginning of modern training simulators. Asmund Laerdal, a successful Norwegian manufacturer of plastic toys, developed the model for training in mouth-to-mouth ventilation.9 Sim One, developed in the mid-1960s, was the starting point for computer-controlled mannequin simulators that could simulate the entire patient.10 As the complexity of simulation models grew, greater importance was placed on technical and nontechnical skills. The concept of crew resource management from the airline industry was integrated in medical workshops and bootcamps as crisis resource management.11

We look forward to seeing you this September at the AAO-HNSF 2024 Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO in Miami Beach, Florida, for all the learning opportunities, festivities, and a truly “simulating” experience!

References

- Owen H. Early use of simulation in medical education. Simul Healthc. 2012 Apr;7(2):102-16. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182415a91. PMID: 22374231

- Markovic¸ D, Markovic-Zivkovic¸ B. Development of anatomical models- chronology. Acta Med Median 2010;49:56-62

- Schnorrenberger CC. Anatomical roots of Chinese medicine and acupuncture. J Chin Med 2008;19:35Y63

- Russell KF. Ivory anatomical manikins. Med Hist. 1972 Apr;16(2):131-42. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300017518. PMID: 4558180; PMCID: PMC1034956

- Spencer L. Chance, circumstance and folly: Richard Berry and the plaster anatomical collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology. In: University of Melbourne Collections, Issue 2. 2008:3-10.

- Parihar RS, Saraf S. Sushruta: the first plastic surgeon in 600 B.C. Internet J Plast Surg 2007;4(2):111.

- https://archive.org/details/columbiauniversi1900colu/page/n33/mode/2up

- Killian G. On direct endoscopy of the upper air passages and oesophagus; its diagnostic and therapeutic value in the search for and removal of foreign bodies. Br Med J 1902;2:560-571.

- Grenvik A, Schaefer J. From Resusci-Anne to Sim-Man: the evolution of simulators in medicine. Crit Care Med. 2004 Feb;32(2 Suppl):S56-7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200402001-00010. PMID: 15043230.

- Denson JS, Abrahamson S. A computer-controlled patient simulator. JAMA. 1969 Apr 21;208(3):504-8. PMID: 5818529.

- Cooper JB, Taqueti VR. A brief history of the development of mannequin simulators for clinical education and training. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004 Oct;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i11-8. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i11. Erratum in: Qual Saf Health Care. 2005 Feb;14(1):72. PMID: 15465949; PMCID: PMC1765785.