The Evolution of Neurotology Fellowship Training to Match Clinical Demands

Tracking the progression of neurotology fellowships toward a standardized curriculum.

Kathryn Y. Noonan, MD, and Bradley Kesser, MD, on behalf of the Skull Base Surgery Committee

In its early years, clinical practice was siloed, resulting in inconsistent techniques and variable quality of care. Over time, an apprenticeship model emerged to standardize and share surgical methods. Dr. Julius Lempert pioneered the apprentice approach for the field in the late 1930s by teaching his fenestration procedure for otosclerosis. Several years later, in 1946, Howard P. House, MD, founded the Otologic Medical Group, offering formal courses in the management of ear disease. It was there, through these teaching efforts, that the first observer tube for the microscope was developed.

Meanwhile, the subspeciality continued to evolve through the pioneering efforts of William F. House, MD, who developed approaches to the skull base that shaped neurotology into the specialty we know today. In 1960, the House Group offered the first otology/neurotology fellowship to share surgical techniques. By 1990, the specialty had expanded to include 31 neurotology programs.1 Fellowship lengths varied widely from as little as three months to as long as 12 months, leading to inconsistent training quality and experiences for trainees. Many physicians also traveled internationally to spend time learning from Ugo P. Fisch, MD, and other giants in practicing the specialty.

This variability prompted a push toward standardization. Through the combined efforts of the American Neurotologic Society (ANS) and American Otologic Society (AOS) in the 1990s, the otology/neurotology community established accreditation status with the American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), structured as a two-year fellowship program.1

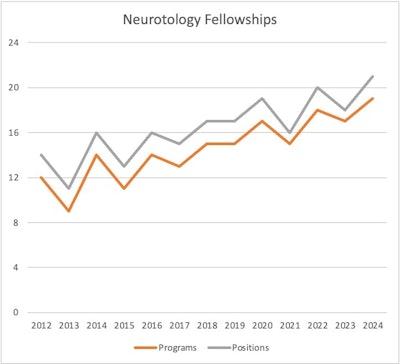

In 1997, the University of Michigan became the first ACGME-accredited program, with nine other programs following closely there afterward. By 2004, the first certifying exam in neurotology was offered by the American Board of Otolaryngology (now the American Board of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery) to accredited fellowship programs. An alternate pathway to certification was granted for a window of seven years for those with predominantly neurotologic practices who did not graduate from ACGME-accredited fellowships, thus establishing quality control through the accreditation status of the specialty. Twenty years later, the number of neurotology programs doubled, with 20 ACGME-accredited programs by 2017, and now 30 programs in 2025 with two more in the pipeline. Figure 1 illustrates fellowship growth over time.

Despite the steady increase in fellowship positions, demand for neurotologists remains high. PracticeLink publishes quarterly data on which specialties are the “hardest to recruit;” otolaryngology, and specifically pediatric otolaryngology, consistently appear on every list. Otology/neurotology intermittently appears on the list of specialties with the highest demand-to-supply ratio, ranking 10th with six open jobs per candidate on the fall 2025 ranking list. This trails behind general otolaryngology (7th) with 7.55 postings per candidate and pediatric otolaryngology (consistently ranked the most difficult to recruit) with 26 jobs per candidate.2

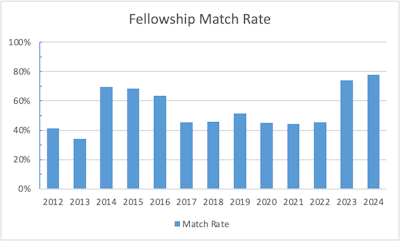

Fellowship interest and match rates remain consistent over time as illustrated in Figure 2. A recent survey of fellowship directors and neurotology fellows examined the priorities of each stakeholder. Judge et al. found that fellows are seeking programs with high operative volumes and a diversity of lateral skull base approaches, while program directors were interested in interview performance, strength of reference letters, and quality of research.3

Neurotology fellowship programs and the ANS have developed a standardized curriculum to ensure quality in the field. A well-attended Neurotology Surgical Bootcamp is offered to all incoming fellows, and a common reading list is published on the ANS website.4 In 2016, ACGME surgical requirements were established, outlining a minimum number of procedures in six different operative areas, including approaches to the skull base, resection of neurotologic tumors, temporal bone resections, reconstruction, vestibular surgery, and rehabilitation surgery.5 Other surgical procedures, including repair of CSF leaks, stereotactic radiosurgery, facial nerve surgery, and middle ear surgery, are also monitored but do not have a minimum threshold. Additionally, fellowship programs require minimums for diagnoses in four domains, including paraganglioma tumors, vestibular schwannoma, facial nerve tumors, and vestibular diseases.

There is some debate as to whether these minimums may be too low. Currently, neurotology case logs require a minimum of 25 tumor approaches and 20 varied tumor resections.5 A recent survey-based article polled ANS members to determine how many surgical cases were needed by procedure to achieve competency. From the analysis of member responses, Harwick et al. recommended minimums of 20 translabyrinthine approaches, 15 retrosigmoid approaches, 18 neoplastic MCF approaches, and 13 non-neoplastic MCF cases for self-perceived surgical competency.6 Fellowship programs and the ACGME track surgical codes and case numbers closely to ensure high-quality standards; the Otolaryngology Residency Review Committee (RRC) can adjust these minimums as needed.

Additionally, further data have recently been published studying qualifications of fellowship directors by tracking their institution of training, H-index, and leadership positions held.7 There are no benchmarks to date for fellowship directors, but the article found a highly accomplished, prolific group. Neurotology has evolved by leaps and bounds over the past half-century and is continuously advancing and looking inward to provide high quality care while meeting the needs of the patient population.

Figure 1: Growth of neurotology programs and fellowship positions over time.8

Figure 1: Growth of neurotology programs and fellowship positions over time.8

Figure 2: Proportion of registered versus successfully matched neurotology fellowship applicants by year. 8

Figure 2: Proportion of registered versus successfully matched neurotology fellowship applicants by year. 8

References

- Gantz BJ. Evolution of Otology and Neurotology Education in the United States. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Apr;39(4S Suppl 1):S64-S68. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001758. PMID: 29533376.

- https://www.practicelink.com/magazine/departments/physician-vital-stats/how-tight-is-the-physician-job-market-in-your-specialty/

- Judge PD, Alvi SA, Tawfik KO. Priorities in the Neurotology Fellowship Match: A Survey Study of Program Directors and Fellows. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018 Sep;127(9):625-630. doi: 10.1177/0003489418783781. Epub 2018 Jun 21. PMID: 29925248.

- https://www.americanneurotologysociety.com/assets/ANS%20Reading%20List%20updated%202023.pdf

- https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/neurotology-case-log-minimums.pdf

- Harwick E, Kutz W, Doerfer K, Nelson RF, Cosetti M, Hong R, Galaiya D, Huang T, Herzog J, Adunka O, Harris MS. Perspectives on Minimum Neurotology Fellowship Case Numbers: A Survey of American Neurotology Society Members. Otol Neurotol. 2025 Sep 1;46(8):877-883. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000004570. Epub 2025 Jun 3. PMID: 40480286.

- Hullfish H, Schachner B, Zippi Z, Kamrava B, Angeli S. Cross-sectional Evaluation of Neurotology Fellowship Directors: A Present-day Snapshot of Leadership. Otol Neurotol Open. 2023 Jul 27;3(3):e036. doi: 10.1097/ONO.0000000000000036. PMID: 38515643; PMCID: PMC10950145.

- https://sfmatch.org/specialty/neurotology-fellowship/5488b3ff-0444-4601-97de-d4a9055d6c8e