Scuba Medicine for Otolaryngologists

Familiarizing otolaryngologists with diving-related concerns and conditions can help mitigate risk.

Jonathan Mallen, MD, Mustafa Mumtaz, and Daniel Roberts, MD, PhD

Scuba-Related Terms

Middle Ear Squeeze: Occurs on descent when external pressure displaces the tympanic membrane inward when the eustachian tube fails to equalize middle ear pressure. There can be a locking effect if the mucosa becomes edematous and the differential is too great to overcome.

Reverse Middle Ear Squeeze: The opposite of middle ear squeeze. On ascent, expanding air in the middle ear displaces the tympanic membrane outward.

Middle Ear Barotrauma (MEBT): Also called barotitis media, this is the most common diving-related ear problem. It occurs when middle ear pressure isn’t equalized with the outer and inner ear, often due to blocked eustachian tubes.

Inner Ear Barotrauma (IEBT): This is a result of a pressure differential between the middle and inner ear. Can affect hearing and/or vestibular function.

Decompression Sickness (DCS or “the bends”): This usually occurs after dives deeper than 10 meters and lasts over 20 minutes. Symptoms appear 15–120 minutes after surfacing. Ear involvement is <20%. Risk is higher for repetitive or occupational diving.

Basic Science

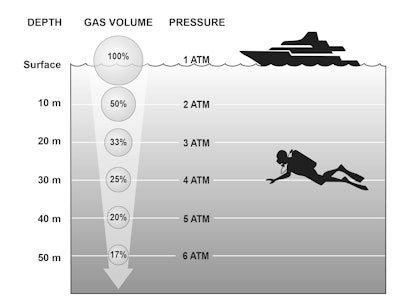

Boyle’s law (P1V1 = P2V2) explains why pressure changes present challenges for divers. As depth increases, gas volumes in closed spaces such as the middle ear or sinuses decrease unless equalization occurs. On ascent, gases expand. The most significant changes occur near the surface. Within the first two to three meters of a dive, divers experience the same ~200 torr pressure differential as during a commercial flight. Atmospheric pressure at sea level is 760 torr (1 atm), increasing by 760 torr for every 10 meters of descent. Early and frequent equalization is therefore essential. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Relationship of underwater depth, gas volume, and gas pressure.1,2

Figure 1. Relationship of underwater depth, gas volume, and gas pressure.1,2

Mechanisms of Injury

1. Barotrauma: Occurs when gas in a closed space expands or compresses without being equalized.

Ears: Dysfunctional eustachian tubes permit pressure differentials between outer, middle, and inner ear, exacerbated by Valsalva maneuvers and continued descent. Ruptures of the tympanic membrane, oval or round windows, or intracochlear membranes may occur, sometimes causing permanent hearing loss or vestibular dysfunction.

Sinuses: Blocked ostia can lead to mucosal injury, bleeding, or rarely, damage to adjacent structures such as the orbit, infraorbital nerve, or skull base.

Lungs: Breath-holding, particularly on ascent, can cause overexpansion and rupture.

2. DCS: Occurs as inert gas, predominantly nitrogen, precipitates out of solution during ascent. The prevailing theory involves venous gas emboli occluding the labyrinthine artery via a right-to-left cardiac shunt, causing cochlear and vestibular dysfunction.

Equalization and Injury Prevention

Divers need to be comfortable with autoinsufflation on land before considering diving. Once in the water, it should be done early and often—about every half meter on descent, starting at the surface. Waiting too long is called “equalizing behind the dive,” and it sets a diver up for failure. Descending feet first helps as well. There are several main techniques divers can perform to help equalize pressure, including:

Valsalva: the classic technique; pinch the nostrils and exhale from the nose

Frenzel: pinched nose with a /kuh/ sound, using the tongue and larynx to push air upward

Toynbee: swallowing with nostrils pinched

Lowry: concurrent Toynbee and Valsalva

If one ear won’t clear, turning the “problem ear” upward can help open the eustachian tube. Divers should avoid repeated ascents, called “yo-yo diving,” which may temporarily relieve ear pain but worsens inflammation and increases barotrauma risk.

Beyond equalization, the basic steps of safe diving include planning the dive, allotting enough air for a slow, staged ascent, and performing decompression stops. After diving, avoid flying for 12 hours after a shallow dive and 24 hours after a deep one.

Decongestants

The use of decongestants is common but controversial. Oral pseudoephedrine has shown benefit in preventing barotrauma in novice divers and has a half-life longer than a typical one-hour dive. Oral phenylephrine has not shown any efficacy as a decongestant. Topical sprays, however, offer scant benefit over placebo. Antihistamines with sedating effects (predominantly first-generation) should be avoided. Decongestants may help select patients but are never a substitute for proper equalization technique. Early, frequent, and correct equalization remains the most effective prevention.

Acute Treatment

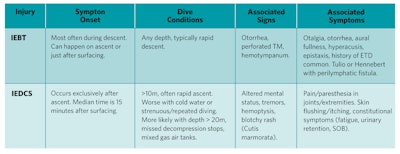

Most scuba-related injuries can be identified through history and physical exam, with audiometry and sinus CT scans serving as potentially helpful adjuncts. IEBT and IEDCS are especially critical to identify and treat promptly. While simultaneous presentation is rare, distinguishing between them can be challenging. Table 1 provides a practical guide to help make that distinction.

Table 1. Differentiating Inner Ear Barotrauma (IEBT) and Inner Ear Decompression Sickness (IEDCS).

Management Techniques

- IEBT/MEBT: Oral and nasotopical decongestants, non-opioid analgesics, audiogram, possible vestibular testing, and avoidance of straining.

- IEDCS: Immediate hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is crucial.

- Uncertain diagnosis: Myringotomy and 100% normobaric oxygen, followed by rapid HBOT, even in unconscious patients.

Emergencies

The Divers Alert Network (DAN) provides free 24-hour emergency treatment recommendations, including information on nearby HBOT centers. You can reach the DAN Emergency Hotline at 919-684-9111.

Return to Diving after Injury

Scuba diving carries inherent risks, but structured evaluation and return-to-dive protocols mitigate these risks. A supervised test dive in a controlled environment, such as a swimming pool, is a prudent first step. Historically, post-injury/post-surgical restrictions have been overly conservative. Modern recommendations allow individualized clearance, adjusting parameters for depth, duration, and risk factors. Evidence-based guidance is available in the referenced Laryngoscope articles.1,2

For safe diving information you can share with your patients, please see “Ear Health Tips for Scuba Diving and Free Diving” on ENThealth.org.

References

- Mallen JR, Roberts DS. SCUBA Medicine for otolaryngologists: Part I. Diving into SCUBA physiology and injury prevention. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan;130(1):52-58. doi: 10.1002/lary.27867. Epub 2019 Feb 18. PMID: 30776099.

- Mallen JR, Roberts DS. SCUBA Medicine for Otolaryngologists: Part II. Diagnostic, Treatment, and Dive Fitness Recommendations. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan;130(1):59-64. doi: 10.1002/lary.27874. Epub 2019 Feb 18. PMID: 30776095.