Treatment of frontal sinus disease circa 1900

In 1900, otolaryngologists in the U.S. had a sophisticated knowledge of sinus anatomy and physiology.

By Lanny G. Close, MD, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, Columbia University, New York

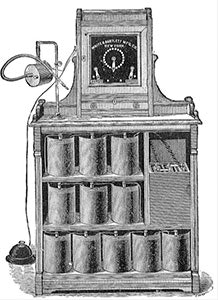

Office electrical DC power source.

Office electrical DC power source.In 1900, otolaryngologists in the U.S. had a sophisticated knowledge of sinus anatomy and physiology. It was known, for example, that normal sinuses evacuate their contents by mucociliary flow and that sinus infections are primarily the result of blockage of the sinus outflow tract(s).

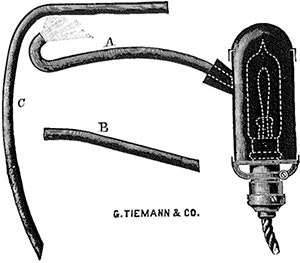

Fiberoptic transilluminator (Chevalier Jackson).

Fiberoptic transilluminator (Chevalier Jackson).The widespread availability of electricity and even x-ray machines (although quite expensive) made the office use of headlights, transilluminators, suction machines, electrocautery units, drills, and fluoroscopy units possible. Antibiotics, however, were not widely available until the mid-1950s.

Thus, although the otolaryngologist could diagnose sinusitis, treatment options were limited. One in 40 deaths in America at that time was the result of intracranial complications secondary to ear and sinus infections.

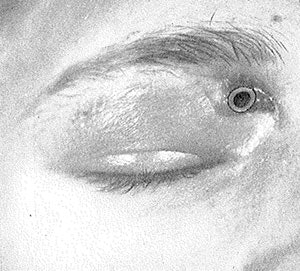

Frontal sinus trephination.

Frontal sinus trephination.Office treatment of sinusitis in 1900 consisted of topical vasoconstriction (4 percent cocaine, 2 percent ephedrine); nasal washes with water, saline, or milk; and local heat. If these treatments were not successful for frontal sinusitis, trephination of the frontal sinus was performed via the intranasal infundibular route or, more commonly, through the bone of the orbital roof or the anterior sinus wall.

Persistent disease generally required highly destructive, disfiguring external surgeries such as those described by Kuhnt (1895) and Riedel (1898). More function-sparing transnasal procedures such as those described by Caldwell (1893) and Lothrop (1897) were rarely attempted.