Update on Choking Hazards and Dangers of Ingesting Lithium Batteries in Children

Scott R. Schoem, MD, Chair, Section on Otolaryngology Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT Can you name the top 10 foods that pose the highest risk of choking hazards for young children? Can you name at least three? (The answers are at the end of the article.) In 2001, 17,500 children aged 14 and younger were treated in emergency departments in the United States for choking with 60 percent of those events caused by food items. More than 160 children die each year from choking events.1,2 Choking is the fourth leading cause of death in children just behind motor vehicle injuries, drowning, and fires. Why are children under four at the greatest risk for choking? Although front teeth start to erupt at seven months, followed by first molars at 15 months and second molars by 26 months, children under four have not developed the sophisticated ability to chew, swallow, and breathe in a coordinated fashion.3 Toddlers need to avoid difficult-to-grind foods such as nuts, seeds, raw carrots, and hard candies. Also, large chunks of apples and tubular foods that fit perfectly into the larynx like hot dogs and whole grapes need to be cut up before giving to toddlers. Non-food items that present the greatest choking hazards include balloons, coins, small toy parts, pen caps, and marbles. Since 1972, the Consumer Product Safety Commission has monitored children’s toys and established recalls. Through their efforts, since 1980, all toys that fit within a small-parts test cylinder of 1 and 1/4 inch must be labeled “for children over 3 years.” National and state Public Interest Research Groups provide the valuable service each year before the winter holidays of publishing lists of new dangerous and toxic toys. Numerous policy statements were developed and distributed by the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngologists (ASPO), publications such as Bright Futures, and HealthyChildren.org all promote parental education and recommend that pediatricians counsel parents at six-month, 1-, 2- and 3-year well-checks on choking hazards.4 SafeKids USA promotes patient safety and injury prevention including choking hazards. Plentiful resources are readily available for pediatricians, parents, and daycare centers. Yet, despite all these efforts, the rate of food-related choking hazards has not diminished over the past 20 years. In one study, 40 percent of parents did not realize that a whole grape was dangerous, 35 percent felt that hot dogs were safe, 30 percent did not identify raw carrots as a choking hazard, and 25 percent did not know the dangers of latex balloons. Clearly, otolaryngologists and pediatricians need a better strategy to directly educate parents, grandparents, and daycare centers and prevent future choking hazards. Another emerging and serious problem that needs to be addressed immediately is the hazard of ingested lithium-ion batteries. While their use in toys mandates a screw top or other protective device, there is no mandated protection of these batteries in common places such as remote controls and music cards. Since 1985, there have been more than 8,100 cases of battery ingestion with 13 reported deaths.5 Lithium ions move from the negative electrode (cathode) to the positive electrode (anode) during discharge with damage to the esophagus within two hours after reported ingestion. Although the “internal ring” sign may be visible on an A/P radiograph to distinguish a flat battery from a coin, this may go unrecognized with delay in removal leading to serious injury or death.6 Since the days of Chevalier Jackson and the Federal Caustic Poison Act of 1927, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery has been proactive in partnering with manufacturers to promote patient safety. When necessary, the Academy’s legislative office will lobby to introduce and support legislation to protect consumers. Currently, the Academy, in partnership with the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Society of Pediatricians, American Broncho-Esophagological Association, and the Society for Ear, Nose and Throat Advances in Children, seeks to reduce choking hazards and to mandate battery fixation to protect against battery ingestion. Answer: nuts, seeds, raw carrots, hot dogs, whole grapes, popcorn, meat and cheese chunks, hard candy, fruit chunks, peanut butter chunks, and chewing gum. 7 References Kaushal P, Brown D, Lander L, Brietzke S, Shah R. Aspirated foreign bodies in pediatric patients, 1968-2010: A comparison between the United States and other countries. Int J Ped Oto. 2011;75:1322-26. Altkorn R, Chen X, Milkovich S, Stool D, Rider G, Bailey C, Haas A, Riding K, Pransky S, Reilly J. Fatal and non-fatal food injuries among children (aged 1-14 years). Int J Ped Oto. 2008;72:1041-46. Committee on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement–Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:601-7. http://www.brightfuturesforfamilies.org/pdf/AppendicesIO.PDF. Consumer Reports, December 2010. Chung S, Forte V, Campisi P. A review of pediatric foreign body ingestion and management. Elsevier 2010;11:225-230. AAP Parenting Corner September 2010.

Scott R. Schoem, MD, Chair, Section on Otolaryngology Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT

Scott R. Schoem, MD

Scott R. Schoem, MDCan you name the top 10 foods that pose the highest risk of choking hazards for young children? Can you name at least three? (The answers are at the end of the article.)

In 2001, 17,500 children aged 14 and younger were treated in emergency departments in the United States for choking with 60 percent of those events caused by food items. More than 160 children die each year from choking events.1,2 Choking is the fourth leading cause of death in children just behind motor vehicle injuries, drowning, and fires.

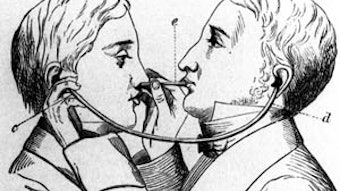

Why are children under four at the greatest risk for choking? Although front teeth start to erupt at seven months, followed by first molars at 15 months and second molars by 26 months, children under four have not developed the sophisticated ability to chew, swallow, and breathe in a coordinated fashion.3 Toddlers need to avoid difficult-to-grind foods such as nuts, seeds, raw carrots, and hard candies. Also, large chunks of apples and tubular foods that fit perfectly into the larynx like hot dogs and whole grapes need to be cut up before giving to toddlers.

Non-food items that present the greatest choking hazards include balloons, coins, small toy parts, pen caps, and marbles. Since 1972, the Consumer Product Safety Commission has monitored children’s toys and established recalls. Through their efforts, since 1980, all toys that fit within a small-parts test cylinder of 1 and 1/4 inch must be labeled “for children over 3 years.” National and state Public Interest Research Groups provide the valuable service each year before the winter holidays of publishing lists of new dangerous and toxic toys.

Numerous policy statements were developed and distributed by the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngologists (ASPO), publications such as Bright Futures, and HealthyChildren.org all promote parental education and recommend that pediatricians counsel parents at six-month, 1-, 2- and 3-year well-checks on choking hazards.4 SafeKids USA promotes patient safety and injury prevention including choking hazards. Plentiful resources are readily available for pediatricians, parents, and daycare centers. Yet, despite all these efforts, the rate of food-related choking hazards has not diminished over the past 20 years. In one study, 40 percent of parents did not realize that a whole grape was dangerous, 35 percent felt that hot dogs were safe, 30 percent did not identify raw carrots as a choking hazard, and 25 percent did not know the dangers of latex balloons. Clearly, otolaryngologists and pediatricians need a better strategy to directly educate parents, grandparents, and daycare centers and prevent future choking hazards.

Another emerging and serious problem that needs to be addressed immediately is the hazard of ingested lithium-ion batteries. While their use in toys mandates a screw top or other protective device, there is no mandated protection of these batteries in common places such as remote controls and music cards. Since 1985, there have been more than 8,100 cases of battery ingestion with 13 reported deaths.5 Lithium ions move from the negative electrode (cathode) to the positive electrode (anode) during discharge with damage to the esophagus within two hours after reported ingestion. Although the “internal ring” sign may be visible on an A/P radiograph to distinguish a flat battery from a coin, this may go unrecognized with delay in removal leading to serious injury or death.6

Since the days of Chevalier Jackson and the Federal Caustic Poison Act of 1927, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery has been proactive in partnering with manufacturers to promote patient safety. When necessary, the Academy’s legislative office will lobby to introduce and support legislation to protect consumers. Currently, the Academy, in partnership with the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Society of Pediatricians, American Broncho-Esophagological Association, and the Society for Ear, Nose and Throat Advances in Children, seeks to reduce choking hazards and to mandate battery fixation to protect against battery ingestion.

Answer: nuts, seeds, raw carrots, hot dogs, whole grapes, popcorn, meat and cheese chunks, hard candy, fruit chunks, peanut butter chunks, and chewing gum. 7

References

- Kaushal P, Brown D, Lander L, Brietzke S, Shah R. Aspirated foreign bodies in pediatric patients, 1968-2010: A comparison between the United States and other countries. Int J Ped Oto. 2011;75:1322-26.

- Altkorn R, Chen X, Milkovich S, Stool D, Rider G, Bailey C, Haas A, Riding K, Pransky S, Reilly J. Fatal and non-fatal food injuries among children (aged 1-14 years). Int J Ped Oto. 2008;72:1041-46.

- Committee on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement–Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:601-7.

- http://www.brightfuturesforfamilies.org/pdf/AppendicesIO.PDF.

- Consumer Reports, December 2010.

- Chung S, Forte V, Campisi P. A review of pediatric foreign body ingestion and management. Elsevier 2010;11:225-230.

- AAP Parenting Corner September 2010.