Contemporary Management of Frontal Sinus Fractures

Advancements in radiography and endoscopic surgery have led to a paradigm shift toward more conservative treatment strategies.

Raj D. Dedhia, MD, and E. Bradley Strong, MD

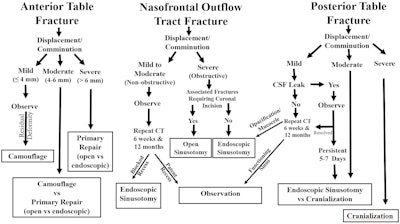

Developing an effective treatment strategy for the treatment of frontal sinus fractures involves assessment of three anatomical regions including the anterior table, frontal sinus outflow tract, and posterior table/dura (Figure 1). All three anatomic areas must be evaluated to determine the best course of action. For complex fractures involving multiple anatomic regions, the treatment algorithm presented may not have unidirectional flow. Surgeons may also combine endoscopic and open techniques depending on their surgical experience and skill set.

Figure 1. Strategy for the treatment of frontal sinus fractures based on assessment of the anterior table, frontal sinus outflow tract, and posterior table/dura.

Figure 1. Strategy for the treatment of frontal sinus fractures based on assessment of the anterior table, frontal sinus outflow tract, and posterior table/dura.

Anterior Table Fractures

The primary risk of anterior table fractures is an aesthetic deformity. However, soft tissue edema makes the prediction of long-term contour deformities challenging. The authors find it helpful to divide these injuries into three types: mild (≤4 mm), moderate (4 – 6 mm), and severe (>6 mm). Multiple studies have demonstrated mild injuries (≤4 mm) have an extremely low risk of long-term contour deformity. Therefore, these injuries can be managed expectantly. Moderate injuries (4 – 6 mm) can be managed either expectantly or with primary repair, depending on the risk-benefit analysis.

Primary repair should be considered when the surgical approach adds little morbidity:

- an existing laceration

- the fracture is amenable to a minimally invasive approach (upper blepharoplasty or endoscopic), or

- the presence of deep rhytids to camouflage the incision.

Expectant management should be considered in patients with low aesthetic demands or when the potential iatrogenic sequalae may be more significant than the injury itself. If a long-term deformity develops after expectant management, a camouflage procedure can be performed. However, most of these patients will require no surgical intervention. Severe injuries (>6 mm) carry an increasing risk of persistent deformity and primary repair is recommended depending on patient preference and aesthetic demands.

Frontal Sinus Outflow Tract

Historically, most frontal sinus outflow tract injuries were believed to result in permanent outflow obstruction and were managed aggressively with sinus obliteration. Frontal sinus obliteration has a 10% – 17% complication rate and may not eliminate the risk of mucocele formation. The most recent literature reveals that fractures resulting in non-obstructive narrowing of the outflow tract can be managed expectantly with repeat imaging; thus, limiting surgical treatment to only those patients with non-functioning sinuses.

Expectant management includes topical nasal steroids, initiating sinus irrigations at one to three weeks post-injury, and routine computed tomography (CT) scan surveillance for sinus re-aeration at six weeks and 12 months (or as indicated by patient symptoms). Patients with persistent opacification will require an endoscopic frontal sinusotomy.

The authors divide these injuries into two groups: mild to moderate (i.e. non-obstructive outflow tract fractures on CT) and severe (complete outflow tract obstruction on CT). Mild to moderate injuries (i.e. non-obstructive) of the frontal sinus outflow tract have a high sinus re-aeration rate (91% for frontal ostia and 98% for frontal recess), therefore expectant management is recommended. Only those patients who do not re-aerate will require an endoscopic frontal sinusotomy. Even if a very small minority of patients developed frontal mucoceles, endoscopic frontal mucocele treatment has been shown to be safe and effective. Severe injuries (obstructive) require primary repair. If a coronal incision is required for other fractures (i.e., naso-orbito-ethmoid) or endoscopic expertise is not available, an open frontal sinusotomy with post op stenting (i.e., open Draf III) can be successfully performed through a coronal incision.

Posterior Table Fractures/Dural Injury

Although the literature remains unclear, there is a trend toward conservative management of posterior table injuries. The authors divide these injuries into mild, moderate, and severe. Mild fractures (0 – 4 mm of displacement, mild comminution/pneumocephalus, and no CSF leak), warrant expectant management with repeat CT scans at six weeks and 12 months or as indicated by patient symptoms. If a CSF leak is present, patients are observed for five to seven days as most leaks will resolve spontaneously. Persistent leaks are repaired endoscopically. If an endoscopic approach is not possible, cranialization can be performed. For moderate fractures (4 – 6 mm of displacement, moderate comminution/pneumocephalus), surgical repair is indicated. The authors advocate for endoscopic repair, however, cranialization is indicated if endoscopic repair is not anatomically feasible or endoscopic expertise is unavailable. Severe fractures (greater than 6 mm of displacement, severe comminution/pneumocephalus, large dural disruptions with CSF rhinorrhea) are not amenable to endoscopic repair and require open cranialization.

Conclusions

Open surgical repair has been considered the “workhorse” of frontal sinus fracture treatment. However, advances in radiography and endoscopic surgery have fueled more conservative treatments including expectant management, secondary camouflage, and endonasal fracture repair. Open frontal sinusotomy and cranialization are now reserved for the most severe injuries or when endoscopic expertise is not available. Long-term follow-up and ongoing research are critical to assess these evolving strategies.

References

- Strong EB, Pahlavan N, Saito D. Frontal sinus fractures: a 28-year retrospective review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;135:774–9.

- Kim DW, Yoon ES, Lee BI, et al. Fracture depth and delayed contour deformity in frontal sinus anterior wall fracture. J Craniofac Surg 2012;23:991–4.

- Grayson JW, Jeyarajan H, Illing EA, et al. Changing the surgical dogma in frontal sinus trauma: transnasal endoscopic repair. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2017;7:441–9.

- Smith TL, Han JK, Loehrl TA, et al. Endoscopic management of the frontal recess in frontal sinus fractures: a shift in the paradigm? Laryngoscope 2002; 112:784–90.

- Jafari A, Nuyen BA, Salinas CR, et al. Spontaneous ventilation of the frontal sinus after fractures involving the frontal recess. Am J Otol 2015;36: 837–42.

- Choi M, Li Y, Shapiro SA, et al. A 10-year review of frontal sinus fractures: clinical outcomes of conservative management of posterior table fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:399–406.

- Dennis SK, Steele TO, Gill AS, et al. Treatment Outcomes With Conservative Management of Frontal Sinus Outflow Tract Fractures. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023.