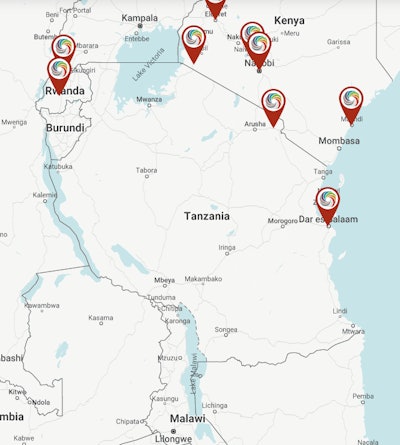

Stories From the Road: Village Life Outreach Project in Tanzania

Village Life Outreach has decades of experience offering robust, meaningful opportunities for volunteers to provide sustainable healthcare support in rural northern Tanzania.

Alfred M. Sassler, DO, on behalf of the Humanitarian Efforts Committee

Coming toward the end of my day-to-day career in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, I began to explore the next phase of my life. I’m not a big fan of the term “retirement” since it connotes an ending of one’s life’s work providing the best care for our patients, which is not my plan at all. I have long been interested in global outreach efforts and observed a sharp rise in interest in this undertaking over the last decade, especially among our younger colleagues. Typically for a scientific-minded person, I began to research the large body of literature on this topic and explore what seems to work and what does not.

My home institution, the University of Cincinnati (UC), is affiliated with several global outreach programs. [The author is currently an Associate Professor of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Emeritus, at UC.] With an interest in the junction and barriers between complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and western or “scientific” medicine, I sought out an organization that could facilitate introductions to alternative healthcare providers in the host country. I also wanted to find a mature organization with an approach that would lead to meaningful and sustainable support. I was lucky enough to have just such an organization in my backyard.

A Decades-Long Initiative to Improve Patient Care in Tanzania

Orthopedic surgeon Clyde Henderson, MD (right), and the author with their language interpreters during patient intake in Roche Village, Tanzania.

Orthopedic surgeon Clyde Henderson, MD (right), and the author with their language interpreters during patient intake in Roche Village, Tanzania.

For volunteers, Village Life provides a robust program of pretravel preparation on everything from vaccination needs, regional history, politics, geography, culture, language, tropical diseases, ethics, the Tanzania Electronic Medical Record (TEMR), and global health outreach concepts.

Village Life volunteers prepare for a clinic set in a temporarily vacated schoolhouse in Nyambogo, Tanzania.

Village Life volunteers prepare for a clinic set in a temporarily vacated schoolhouse in Nyambogo, Tanzania.

Sign for the Shirati Health Education and Development Foundation (SHEDF) office.

Sign for the Shirati Health Education and Development Foundation (SHEDF) office.

Location and Background

Only Just Beginning

The author (middle) and an interpreter during patient intake at the UC Health clinic in Roche Village.

The author (middle) and an interpreter during patient intake at the UC Health clinic in Roche Village.

Our trip afforded a truly comprehensive introduction to the world of global healthcare outreach and a taste of some of the challenges and successes that are possible. Village Life Outreach is ready to learn more and spread the word to others who might be interested. Are you ready to take a leap and participate in global healthcare outreach? It is exciting, heartwarming, and invigorating and can provide sustainable impact to individuals and communities. We are only just beginning.

For a more detailed account, continue reading below for Dr. Sassler’s four-part travel log of his incredible experience volunteering and traveling in northern Tanzania with the Village Life Outreach Project.

Travel Log Part I: Observations from Mwanza

Day 1: Hotel Tilapia and a first visit to Bugando Hospital

Our delegation, including UC faculty and Village Life leadership, arrived in Mwanza after two long flights the day before, for a short rest at a local hotel with time for sleep, a shower, and breakfast. We then took a short hop on a regional carrier from Kilimanjaro Airport to Mwanza Airport. We checked into the lovely Hotel Tilapia and then several of us went to visit Bugando Hospital in town, an affiliated teaching hospital of the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS).

Bugando Hospital is a major regional referral hospital for the Tanzanian Health Ministry and comprises 500 inpatient beds, numerous outpatient clinics and a variety of specialty services. John Wyrick, MD, a prior UC faculty member and veteran orthopedic trauma and hand surgeon was a member of our group. He had made multiple prior trips to this hospital as a volunteer and offered to have us accompany him on rounds and meet with his senior resident, as he had several complex cases scheduled during his visit. This gave us an opportunity to see how things worked at this important teaching and referral center.

Days 2 and 3: Bugando Hospital and meeting Dr. Cecilia Protas

The next morning, we all formally met with the clinical leadership of the hospital (set up by Chris Lewis, MD, and Village Life) including several department heads or their representatives to find out about their mission, plans, and critical needs and how we could potentially assist in meeting their goals.

I had the rare opportunity to spend the rest of that day with Cecilia Protas, MD, a faculty attending physician in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. We discussed her training in Tanzania, her practice and her facilities. I got to observe one of her clinics, which included several CUHAS medical students and a general practice student from a smaller town outside the city who was in his second and final year of advanced ENT training (more on this later). We made plans to come back the next morning to observe in her OR, and I also brought along some lectures and teaching materials to review at her request.

Otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon Dr. Cecilia Protas (center) with the author (left) and his wife, Leigh Sassler, RN, at Bugando Hospital.

Otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon Dr. Cecilia Protas (center) with the author (left) and his wife, Leigh Sassler, RN, at Bugando Hospital.

This introduction to a major teaching and referral hospital allowed us to see some of the “nuts and bolts” of the healthcare system in Tanzania. We saw dedicated and committed professionals doing their best with very limited resources. Speaking from an in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery standpoint, Tanzania has a population of roughly 66 million people and about 65 otolaryngologists.

Bugando Hospital had eight otolaryngologists on staff to serve a referral population of well over one million. (Exact numbers are difficult to know, but the city has a population itself of over 700,000, and the medical center receives referrals from a much wider area.) I was surprised and pleased to learn that two of the eight attending otolaryngology faculty were women.

Blood transfusion warming by an open window at Bugando Hospital.

Blood transfusion warming by an open window at Bugando Hospital.

Hand-laundered bed sheets, gowns, and drapes drying on the lines at Bugando Hospital.

Hand-laundered bed sheets, gowns, and drapes drying on the lines at Bugando Hospital.

Dr. Protas had instituted a program to locate and train general practice physicians who work in smaller district and community hospitals that are interested in learning more about otolaryngology-head and neck surgery and bring them to Bugando for a two-year training program to better care for routine ENT issues in their patients at home. The fellow I observed, in his second year of this training, was adeptly seeing and treating clinic patients and performing tonsil and adenoid surgery very skillfully and efficiently with little input needed from Dr. Protas. This was similar to seeing a third- or fourth-year resident at work at UC. Such initiatives vastly improve the care available in rural areas and improve the quality of the referrals for inundated providers at the referral centers. That is the kind of creativity and initiative that we saw in resource-poor situations and were continually impressed with.

In our brief time at Bugando Hospital, I learned about some gaps in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery education for these dedicated individuals as well as many equipment needs that I hope to be able to help with in the future. Some of this simply involves connecting people online and this is already happening. I want to underscore that there are so many opportunities to improve the care that is given to the people of Tanzania and there are many groups that are already helping. For example, Weill Cornell Medicine (Cornell University’s medical school and biomedical research unit) helps support Bugando Hospital.

But the magnitude of the problems can look overwhelming from the charmed perspective of healthcare in the United States and other high-income countries. You will see that a bit more clearly in the next section.

Travel Log Part 2: Mobile Clinics in Shirati

Day 4: Arriving in rural Shirati

After those brief two days in Mwanza, we struck out by van for our next destination, the town of Shirati, the next morning. This smaller town is on the northern border along Lake Victoria. The approximately seven-hour drive allowed us to see urban, suburban, town, village, and rural areas all in one day. The residences varied from single homes to apartment tracts, mud huts with thatched or metal roofs to sheet metal shacks crammed together in the outskirts of the city. We saw market areas with all manner of goods and foodstuffs for sale along largely unpaved roads outside the major highways. We often saw open sewers with slabs across them to hold shopping stalls.

Along the dirt roads, foot traffic was most common, followed by small motorcycles (125-250cc “picky-picky bikes,”) some automobiles and trucks, three-wheeled, open vehicles called “tuk-tuks,” motorcycle-truck hybrids deftly carrying goods, over-filled buses and bicycles. Along the roads, we also saw uniformed schoolchildren attending both government and private primary and secondary schools, shepherds moving their flocks of cattle, sheep, and goats to proper grazing areas (grazing is open for anyone to use in Tanzania), and women carrying surprisingly large loads on their heads (remember this for later).

Toward the later afternoon, we saw many people in the rural areas carrying water and doing their washing in streams off the roadways. We also saw a few “urban farmers” using small patches of land next to the roadways to scratch out gardens, growing vegetables by hand.

The author and his wife, Leigh Sassler, RN, at the entrance to the SHED Foundation compound in Shirati.

The author and his wife, Leigh Sassler, RN, at the entrance to the SHED Foundation compound in Shirati.

We wholeheartedly enjoyed a cool shower. (It’s hot near the equator this time of year!) Our small fan powered by my computer battery and our mosquito netting were essential as we journaled and then tuned into the sounds of the rural Tanzanian night. I am still not sure what animals we heard!

Day 5: Mobile clinics in Shirati

The next morning at our wonderful outdoor breakfast, we could actually see everyone and start to get to know who was who. We boarded vans with the same multilingual, professional drivers we would have for the rest of the trip and drove to our mobile clinic stop for the day at a primary school compound in the village of Nyambogo.

After a bouncy 45-minute drive along dirt roads, we arrived and set up our clinic in one of the school buildings that was vacated for us that day. The medications and lab supplies had been organized the evening before back at the SHEDF compound by Village Life staff and volunteers and was now unloaded from travel chests along with the IT equipment to run our Tanzania electronic health record (TEMR) off of solar power and batteries.

The system was built and designed by Village Life using volunteer and staff IT and clinical expertise. It has been functional for four or five years and is being constantly improved. The system helps with documentation and tracking data on social determinants, disease incidence, lab results and medication use. The system was easy to learn and download to personal devices, including phones, iPads, and laptops. All clinicians had a training session on using the TEMR prior to the trip and again during the trip with help available in real-time while in clinic, too.

A village member carried out prescreening to arrange who was to be seen that day and clinic intake (my wife was assigned there in the morning session) to collect demographics, chief complaints, vital signs, and so on. Next, all the clinicians, including faculty, residents, nurses, nursing practitioner (NP) students, and medical students, saw the patients. I was paired with an NP student who was a very experienced oncology nurse in her day job in Kansas. We were able to converse through the interpreters and examine the patients.

Our top priority was to ask about and document potential symptoms of malaria, tuberculosis, intestinal parasites, and schistosomiasis (carried by snails in the shallow waters of nearby Lake Victoria and its estuaries). We had rapid lab tests available for malaria and could then institute treatment. Other issues that were commonly seen were musculoskeletal issues, especially in women (remember those big loads on their heads?), dental issues, vision problems, headaches, and light-headedness, and even STD symptoms.

After our exams, we made presumptive diagnoses, and we could then order medications, lab testing, or referral for further evaluation and treatment (such as for dental work or eye exams at the Shirati District Hospital). The patients were then escorted to the pharmacy and lab area where our trilingual interpreters helped explain and review all medication instructions and answer questions that arose. This became interesting when we saw families of as many as six people with various treatments for different family members. When we determined a need to treat STDs in a patient (with medications administered in the pharmacy area whenever possible), we had them take treatment to administer to their partner(s). Patients were also given toothbrushes, soap, and “reader” eyeglasses if needed.

A relatively new program had been initiated to have “group visits” for those with common issues such as musculoskeletal problems. These individuals were taken to a separate area where their problem and its treatments and prevention could be discussed at length and all questions answered in a group, thus maximizing patients being cared for. If they had other issues, they could still be seen in the general clinic space.

We had a brief midday break for a boxed lunch and then resumed in the afternoon. I spent my afternoon in the medication dispensation section discussing the “whys” and “hows” of treatment courses through the interpreters, mostly in the Luo language. This was an efficient and effective way to provide a significant range of healthcare services for people who otherwise did not have readily available access.

Throughout the day, the schoolchildren in the adjacent buildings and rooms continuously gawked at us, as did the waiting patients (many of them children, as well). Undoubtedly, we were quite a novelty and likely much more fun to see than the lessons they were missing. In fact, I met one of the teachers, who might have been just a little cross with a few of the boys who wanted to show off to a group of us.

When we traveled back to the SHEDF compound that evening, we cracked open a beer or two before another wonderful meal and discussed our day. As a routine, each evening we heard clinic numbers (patients seen, malaria testing done, percent of tests positive, etc.) After dinner, we had brief, extemporaneous talks by members of the group on topics such as teen depression and suicide by Steven Kniffley, Jr, MD, a clinical psychologist and Senior Associate Dean for DEI at UC College of Medicine. Dr. Esther also gave a talk on a new program to identify and treat sickle cell anemia in Tanzania, who had started the rapidly growing program at the Shirati Hospital.

There was also an opportunity to go around the tables for everyone, and everyone to discuss their experiences. This was a great way to help deal with the cultural onslaught that we were all experiencing no matter what level you were at in your career or training.

A new eye clinic at Shirati Hospital, constructed from shipping containers.

A new eye clinic at Shirati Hospital, constructed from shipping containers.

The next day was a Sunday so there were no clinics in this religious community. We took the day to visit the Shirati District Hospital, which is supported by the Mennonite Church. We also had an opportunity to hike up a local peak with sweeping views of the surrounding valley and later that evening visited the Victoria lakefront.

Travel Log Part 3: Roche Village and Celebrating a New Maternity and Child Health Care Center

Formal dedication of the Haire Reproductive and Child Health Center with community members and Village Life Leadership and staff in attendance.

Formal dedication of the Haire Reproductive and Child Health Center with community members and Village Life Leadership and staff in attendance.

The following day, we loaded up the vans and drove to Roche village to see patients in the morning at our clinic building. The afternoon was set aside for the dedication ceremony of the new maternity and child health care center on the same site. The community partners initially felt that a local clinic and improved clean water supply were top priorities for improved healthcare in their area. So, Village Life facilitated those goals. Subsequently, a high rate of maternal and infant mortality in the perinatal period was noted in the area. So, the consortium decided to add a dedicated facility on the same property to address this issue.

The clinic’s well stocked and organized mobile pharmacy.

The clinic’s well stocked and organized mobile pharmacy.

Travel Log Part IV: Exploring a Maasai Village

Days 8 and 9: Packing up and sightseeing

We had come to the end of the service portion of this trip. We packed up the clinic and our own things and prepared for the eight-hour van trip the next morning to Kenya to spend some time seeing the wildlife and wonders of the Serengeti on safari as well as other wildlife parks and sights of Nairobi before returning home.

During this part of the trip, we were able to visit a Maasai village (within the Mara region of the country), where we saw an example of how this community lives and what they view as appropriate healthcare.

I happen to have an interest in the junction and barriers between complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and western or “scientific” medicine. My reading has revealed that indigenous health workers provide fully half of the healthcare in the world. These community providers are trained within their culture and often within their family. They are adept at herbal remedies as well as having a deep “ethnic knowledge” of cultural norms, allowing them to advise and intervene in health and healthfulness for their communities. They tend to have keen skills of observation and they are afforded the trust of their patients implicitly. They are called on to assist in birthing, illness (“dis-ease”) of the body and the mind, and impending death.

Going into this trip, I wanted to see firsthand how these practices affect patient care outcomes in resource-poor areas and how such healthcare practices are reflected by and in our practice here in the United States. I have noted an increase in interest and use of CAM in my own patients and always seek to learn more. I would like to help determine how we can leverage CAM and mainstream medicine to optimize care for patients everywhere. I felt that experiencing healthcare in a developing country would also give me an opportunity to learn where indigenous healthcare fits into the picture.

In the Maasai village we visited, people spoke the Ma language rather than the Luo we had heard during the last several days of our trip. But there were interpreters who allowed us to communicate. Most families have someone who is adept at herbal remedies. The Maasai people consume fresh cow’s blood mixed with unpasteurized milk to provide nutrition and avoid disease. Pregnant women ingest extra amounts. They have their babies at home, often assisted by midwives. Some children have recently begun to go to government schools, but that requires a birth certificate. So, they have to take newborns to the hospital within the first two weeks after birth for registration and a polio vaccination. This is a large cultural (and healthcare) change, and there is controversy as to whether this is a positive step. The Maasai people consider their unique culture to be a part of their “home.”

Needless to say, this experience provided great insight into just one of the gaps and barriers between indigenous and scientific medicine and healthcare. I would have much to ponder during the long trip back home over the next day and a half.