Second Victims in Otolaryngology

Learn how to help protect yourself and your colleagues from a growing epidemic of physician suicides in the U.S.

Heather M. Weinreich, MD MPH, Stephanie A. Joe, MD, Noel Jabbour, MD, and Soham Roy, MD, MMM

Content warning: This article discusses suicide and suicidal feelings, which some individuals may find distressing.

During a quarterly meeting of the AAO-HNSF Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee, two of the current authors realized that three physician friends had taken their own lives in the course of just three months. One death was a former classmate rumored to have had a poor patient outcome. Another was a friend from medical school. And the third death was an otolaryngology colleague. There is an epidemic of physician suicides in the United States with an estimated 300 deaths per year.1 The answer to “why” may never be fully known but the gravity of being a physician is a component.

It was out of our grief that the panel “Second Victims in Otolaryngology: Protecting Yourself from a Growing Epidemic” was formed for the AAO-HNSF 2024 Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO. The panel was our way of sounding the alarm and creating a safe space for our members.

Second Victim Syndrome (SVS) plagues the healthcare community and contributes to the epidemic of physician suicides, burnout, and resignation from the profession. SVS was first coined as a term by Albert Wu, MD, MPH, in 2000, who described the concept where an injured patient and family (first victims) are at the center of an adverse outcome, while physicians and caregivers who feel responsible for the adverse event become the second victims. Surgeons often feel solely responsible for these events, and the unwillingness of surgeons to discuss adverse outcomes impedes facing these events as learning experiences.

In 2010, the Annals of Surgery reported that almost 9% of nearly 8,000 surgeons were concerned that they had made a major medical error in the previous three months.2 Those who reported an error in the prior three months had a statistically significant adverse relationship with mental quality of life measurements, all three domains of burnout, and symptoms of depression. Why are we so impacted by these experiences?

Our “physician personality” is characterized by perfectionism, hard work, an inability to relax, a reluctance to allocate time for ourselves, and an exaggerated responsibility to our patients.3 When surveyed about attributes that make a good doctor, 74% of physicians placed “humaneness” as number one.4 Humaneness is a disposition to be kind, forgiving, compassionate to the suffering of others, and wanting to do something about it. But what makes a good doctor is also a weakness. We are not machines. We work in an environment that is intolerant to this simple fact. The environment of medicine is a stoic arena whereby stress is normalized, and distress is inherent, even requisite. Sleep deprivation and long hours exasperate the situation.

As a result, we burn out. The American Medical Association (AMA) defines burnout as a long-term stress reaction of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a feeling of decreased personal achievement.5 In a 2021 survey of otolaryngologists, 16% reported burnout, 4% reported depression, and 17% reported both with over 70% reporting it significantly affected their lives.6

Being “burned out”, along with a woman, a resident, having less experience, feeling unrewarded, overwhelmed, or perceiving work/life imbalances, are all risk factors for SVS.7 Even without a medical error, poor outcomes happen in medicine and physicians may blame themselves. Even if our work hours allow time to seek help, the stigma and confidentiality concerns hold physicians back.

Some physicians manage. Some do not and self-medicate. The risk of developing a substance abuse disorder is associated with a recent medical error, lower quality of life, lower career satisfaction, and depression. In a survey of U.S. physicians,8 26.7% of physicians met the criteria for substance abuse. When broken out by gender, 12.9% of men met the definition of alcohol abuse/dependence while the number was higher among women at 21.4%. In our field, about 15% of otolaryngologists met this definition.

Substance abuse disorders are a risk factor for suicide ideation. Suicide ideation is further driven by depression, increased workload, work inefficiencies, lack of autonomy, work/home conflict, and feelings of having no meaning at work. Women physicians are more at risk. In a study published in February 2025, women physicians had higher rates of suicide than women in the general population while a reverse trend was seen in men.9 At our panel, we ask by show of hands how many participants know of a physician who has attempted or committed suicide. Every year, it is over 50%.

How do we start to help ourselves and our fellow physicians? First, we should accept that as physicians, we may experience poor patient outcomes, and it may be because of error. It is human to be sad or upset by a poor outcome. We cannot and should not ask physicians to ignore their emotional response. Second, we can create environments that prevent our colleagues from spiraling. We can start by addressing the systemic issues that create a toxic environment. And third, we can create support structures for our colleagues and residents.

Christine Sinsky, MD, of the AMA notes, “While burnout manifests in individuals, it originates in systems.”10 The top five causes of burnout reported by otolaryngologists are system-based causes:6

- Too many bureaucratic tasks

- Lack of respect from administration, employer, colleague, or staff

- Insufficient compensation/reimbursement

- Increasing computerization of practice

- Spending too many hours at work

When we examine these causes, two concepts come into play: moral injury and administrative harm. Moral injury is defined as an act of transgression that creates dissonance and conflict because it violates assumptions and beliefs about right and wrong and personal goodness.11 Dovetailing with this is administrative harm, defined as adverse consequences of administrative decisions that directly influence patient care and outcomes, professional practice, and organizational efficiencies. These decisions may be driven by profits often prioritizing short-term gains while neglecting the longer-term negative consequences.11

In 2023, The New York Times published “The Moral Crisis of America’s Doctors,”11 a piece that circulated on and resonated with members on the AAO-HNS member forum ENTConnect. The article discusses our constant battle with the pressure of the system that betrays our humaneness. It can tip the physician from coping with an adverse event to a downward spiral of emotion.

This difference in terminology between burnout, moral injury, and administrative harm is important because it reframes the problem and the solutions. Focusing on burnout assumes the individual is deficient, lacks resources, or does not have the resilience to withstand the environment. Talbot et al. commented, “…it is absurd to believe that yoga will solve the problems of treating a cancer patient with a declined preauthorization for chemotherapy, having no time to discuss a complex diagnosis, or relying on a computer system that places metrics ahead of communication.”12 The sources of burnout and SVS need to be addressed.

To protect and advocate for ourselves, we need to recognize that we are not alone. Peer support refers to care from a colleague who has had the same experiences. This support is often provided through a formal program either internally in local health systems or through external programs. Trained volunteers are matched with a healthcare provider of a similar specialty who are not within the same department. A peer supporter provides a “safe space” for confidential conversations with their troubled colleagues. Supporters provide nonjudgemental emotional support and validations. The exchange of shared experiences provides validation of the emotions and reactions surrounding the adverse event.

Part of the value of peer support is that it helps us develop resilience and reduce burnout. This has been born out in studies by a pioneering leader in this field, Jo Shapiro, MD. Conclusions are summarized by the following sample statements: “Speaking with a colleague about emotional stressors is correlated with resilience and positive coping after adverse and other emotionally stressful events.”13 Talking to a peer provides a sense of balance and professional affirmation without the need to provide exhaustive background concerning the physician’s duties and circumstances.”14 Tait Shanafelt is another pioneer who authored a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to reduce physician burnout.15

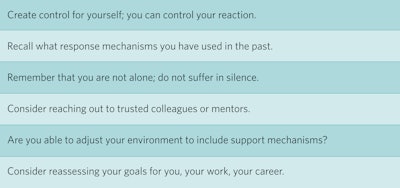

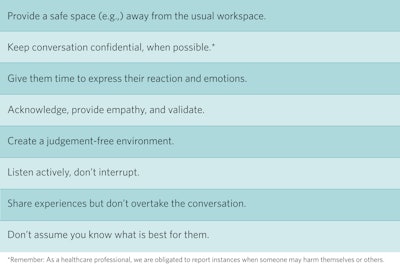

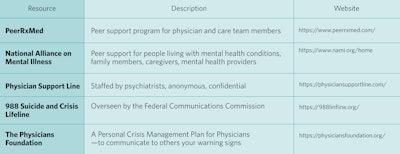

Tables 1 and 2 list ways colleagues can provide support for each other. Table 3 provides a sample of external resources for colleagues who prefer not to use internal system programs. Additional resources and reading are listed at the end of this article.

Table 1. What can I do for myself?

Table 2: How can I be supportive of my peers?

Table 3. External resources for physicians.

To effect cultural change, health system leadership must be involved in supporting healthcare providers in times of need to help them achieve wellness, resilience, and manage of burnout. The Joint Commission has commented on SVS and offered recommendations.15 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 17 provides resources for starting a peer support program and the AMA provides free resources for peer support.13

Several health systems across the U.S. are engaged in these efforts. The University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System has committed to supporting all physicians and staff members with its “Care for the Caregiver” program. They also have a peer support program, “Compassionate Alliances for Resilience and Empowerment” (We-CARE), which is available for faculty of its college of medicine. Stanford Medicine has the WellMD program and provides a chief wellness officer course. Dr. Shapiro, mentioned above, is a founding member of the Center for Professionalism and Peer Support at The Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Other health systems across the nation provide resources in the development of such supportive programs; examples include Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Oregon Health Sciences University School of Medicine.

Finally, we need to be vigilant towards our residents. In 2024, Noel Jabbour, MD, otolaryngology residency program director and vice chair of education at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center joined the panel to discuss the impact of workplace pressures on physicians in training. He emphasized that while all physicians feel these pressures, trainees experience them even more acutely. On the front lines, they have a firsthand view of traumatic events—experiences not just stored in the mind but also in the body, as detailed in The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, MD.17

When unexpected patient morbidity or mortality occurs, the complication happens to the patient—but as compassionate physicians, we physically absorb the trauma, triggering a heightened sympathetic nervous system response. This fight-or-flight arousal can persist long after the event, impairing our ability to function within our optimal “window of tolerance.”18 Just as childhood trauma can stunt physical growth, trauma in residency can hinder surgical development.

To mitigate this, we must foster “no shame” cultures within our departments. Processing trauma within a community of empathic witnesses leads to far better healing than when it is ignored or, worse, met with shame and blame. Author and psychologist Brene Brown, MD, remarks on this phenomenon.

“If you put shame in a petri dish, it needs three things to grow exponentially: secrecy, silence, and judgment. If you put the same amount of shame in a petri dish and douse it with empathy, it can’t survive.”19

As otolaryngologists and as surgical educators, we must design quality improvement conferences with empathy in mind. These meetings are a primary space to serve as empathic witnesses to each other’s processing of traumatic events. We must be mindful of this in our public responses during these meetings and in our private interactions with trainees before and after. The presence of an empathic witness can soften the psychological injury of an SVS experience and become a catalyst for healing.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, text "STRENGTH" to the Crisis Text Line at 741741 or go to 988lifeline.org.

Suicide Prevention Resources for Physicians

https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/preventing-physician-suicide

https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702599

https://drlornabreen.org/about-lorna/

Recommended Reading

Van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

Siegel, Daniel J. 1999. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guilford Press.

Brown, Brené. 2012. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. New York: Gotham Books.

References

- Matheson J. 2025. "Physician Suicide." American College of Emergency Physicians. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/wellness/wellness/wellness-week-articles/physician-suicide/.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, Collicott P, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Freischlag J. 2010. "Burnout and Medical Errors among American Surgeons." Annals of Surgery 251 (6): 995–1000. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3.

- Collie R. 2012. "The 'Physician Personality' and Other Factors in Physician Health." CMAJ 184 (18): 1980–4329. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4329.

- Dopelt K, Bachner YG, Urkin J, Yahav Z, Davidovitch N, Barach P. 2021. "Perceptions of Practicing Physicians and Members of the Public on the Attributes of a 'Good Doctor.'" Healthcare 10 (1): 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010073.

- American Medical Association. 2023. "What Is Physician Burnout." Accessed March 3, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/print/pdf/node/88521.

- Martin KL, Koval ML. 2021. "Medscape Otolaryngologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report."

- Marmon LM, Heiss K. 2015. "Improving Surgeon Wellness: The Second Victim Syndrome and Quality of Care." Seminars in Pediatric Surgery 24 (6): 315–318. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.08.011.

- Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, Tan L, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J, Boone S. 2015. "The Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders in American Physicians." American Journal of Addiction 24 (1): 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12173.

- Makhija H, Davidson JE, Lee KC, Barnes A, Choflet A, Zisook S. 2025. "National Incidence of Physician Suicide and Associated Features." JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4816.

- American Medical Association. 2022. "Christine Sinsky, MD, on What Physicians Need to Know About Burnout in 2022." Accessed March 3, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/christine-sinsky-md-what-physicians-need-know-about-burnout.

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. 2009. "Moral Injury and Moral Repair in War Veterans: A Preliminary Model and Intervention Strategy." Clinical Psychology Review 29 (8): 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003.

- Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. 2019. "Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout." Federal Practitioner 36 (9): 400–402.

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. 2016. "Peer Support for Clinicians: A Programmatic Approach." Academic Medicine 91 (9): 1200–1204. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001297.

- Plews-Ogan M, May N, Owens J, Ardelt M, Shapiro J, Bell SK. 2016. "Wisdom in Medicine: What Helps Physicians after a Medical Error?" Academic Medicine 91 (2): 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000886.

- West, CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. 2016. "Interventions to Prevent and Reduce Physician Burnout: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." The Lancet 388 (10057): 2272–2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X.

- The Joint Commission. 2018. "Quick Safety - Supporting Second Victims." Accessed March 3, 2025. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/newsletters/quick-safety-issue-39-2017-second-victim-final3rev.pdf.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2022. "Care for the Caregiver Program Implementation Guide." Accessed March 5, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/candor/modules/guide6.html.

- Van der Kolk B. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

- Siegel DJ. 1999. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guilford Press.