Be Present, Mindfulness Works

In the space of a few weeks, the coronavirus outbreak became an all-consuming global, national crisis. Changing day-to-day life in unprecedented ways, it touched all of us and will be the focus for many more months to come. The collateral effect of this pandemic on healthcare providers’ well-being is emerging as clinicians face even greater workplace distress that will likely exacerbate existing levels of burnout.

Sonya Malekzadeh, MD, Member of the AAO-HNS Physician Wellness Task Force

Sonya Malekzadeh, MD

Sonya Malekzadeh, MDIn the space of a few weeks, the coronavirus outbreak became an all-consuming global, national crisis. Changing day-to-day life in unprecedented ways, it touched all of us and will be the focus for many more months to come. The collateral effect of this pandemic on healthcare providers’ well-being is emerging as clinicians face even greater workplace distress that will likely exacerbate existing levels of burnout. It is not surprising that the National Academy of Medicine warns of a wave of physical and emotional harm amounting to a “parallel pandemic,” urging us to develop clear strategies to address clinician well-being during and after the COVID-19 crisis.1 Although this complex problem requires a shared response at the national and health system levels, there are individual strategies that can help mitigate the uncertainty and anxiety surrounding this particular time.

Mindfulness has gained traction as a tool to combat physician stress and burnout. Most of us have heard the term, and it can evoke a whole host of ideas but essentially refers to paying attention on purpose, non-judgmentally, to what is happening in the present moment. In other words, we need to intentionally focus our attention on the here and now instead of dwelling on the past or worrying about the future. Our focus is not meant to judge thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations but to experience and acknowledge them with compassion. As we become aware of our internal and external surroundings, we are creating a sense of calm and acceptance.

Based on Buddhist philosophy, mindfulness was first introduced into Western medicine by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s. His techniques were primarily developed for stress management but evolved to include the treatment of a variety of health-related disorders. According to his research, mindfulness practices can lead to a less intense stress response, which in turn has several benefits, such as decreasing hypertension, strengthening the immune system, and reducing pain levels. These skills can also enhance day-to-day well-being by improving mood and alleviating feelings of unease, anxiety, and fear.

To better understand the positive health effects of mindfulness, let’s reflect on the stress response and the connection between our chronically stressful lives and our body’s response to stress. When the mind perceives an emotional or physical threat, cortisol and other stress hormones are released in the “fight or flight” response, preparing us to meet the challenge. Unfortunately, this survival mechanism can also kick in during non-life-threatening situations, such as work burden and family tension. When the threat disappears, cortisol levels drop. The trouble is that we rarely deal with one stressor at a time and chronic low-level stress keeps cortisol from returning to baseline. Over time, the body is dysregulated and there are deleterious effects of chronic stress. Mindful practice utilizes our mind-body connection to “de-stress” or counter the stress response.

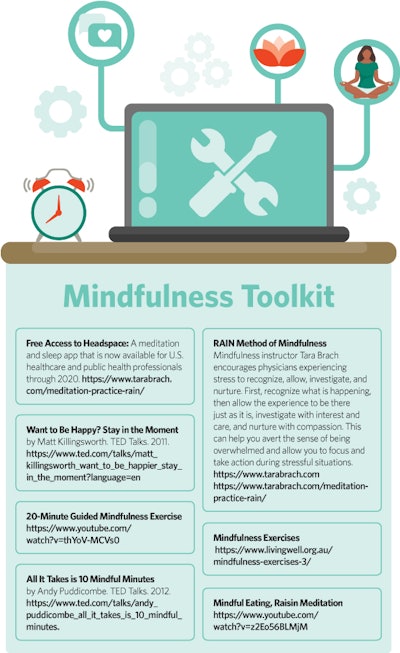

Being mindful doesn’t need to be complicated. There are simple and brief exercises that can be effortlessly incorporated into your daily routine. Mindfulness techniques vary in effectiveness from one individual to another, and the key is to experiment until you find which resonates best with you. For some it’s focused breathing, and for others it’s movement and exercise—whatever technique works for you is what you should pursue. Like learning any new skill, mindfulness takes time and practice. The mind is a busy place and it’s natural for the mind to wander, but when it does, you can learn to quiet your mind by gently refocusing thoughts back to the exercise. Mindfulness is like a muscle; the more you exercise it, the better it will work when you need it. Remember, with mindfulness there is no way of doing it wrong. Accept whatever you might be feeling or thinking without trying to change it or your reactions. Recognize unpleasant sensations, thoughts, and feelings as temporary and fleeting, observing them objectively without reaction or judgment and not worrying about doing it right or different but noticing what is.

My first introduction to mindfulness was through a required institutional-sponsored mind-body medicine retreat on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Always the skeptic, I was reluctant to invest the time and energy on what I viewed as an overhyped trend, lacking substance or scientific basis. Over the ensuing four days, I gained a different perspective. I realized that mindfulness did not require me to chant, hold hands, or sing “Kumbaya.” In fact, all I needed was the willingness to sit quietly, giving my mind the space and silence to process thoughts. Like most physicians, my life is full of stressors from work, home, and digital devices. A self-professed multitasker, I am not always fully present for patients or family. As my practice of mindfulness develops, I have learned to slow down and become less reactive and more accepting of events out of my control. While I can’t entirely eliminate stress, I can be more adaptable to the pressures. Mindfulness is the self-care tool I need to be the best possible doctor for my patients and the healthiest possible version of me for my family.

Mindfulness is not a magic bullet. It will not address the increasing pressures of an ever-evolving healthcare system, nor the anxieties surrounding a global pandemic. However, it can play an important role in how we respond to these physically and emotionally demanding times. After all, we have to take care of ourselves in order to have something left to care for others.

References

- Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Nasca T. Preventing a Parallel Pandemic — A National Strategy to Protect Clinicians’ Well-Being. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2011027.