What Matters in the End: Care at the End of Life in Otolaryngology

Often otolaryngologists do not discuss dying with their patients, as their traditional role is to prolong and improve life. Over the past few decades, there has been an explosion of interest in popular culture about end-of-life care.

Andrew J. Redmann, MD, Roger D. Cole, MD, Susan D. McCammon, MD, and Andrew G. Shuman

Presented at the AAO-HNSF 2019 Annual Meeting & OTO Experience in New Orleans, LA

Often otolaryngologists do not discuss dying with their patients, as their traditional role is to prolong and improve life. Over the past few decades, there has been an explosion of interest in popular culture about end-of-life care. In particular, Paul Kalanithi’s 2016 posthumous autobiography, “When Breath Becomes Air,” about completing a neurosurgical residency after a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer, hit number one on The New York Times bestseller list, illustrating a cultural interest in what a “good death” looks like.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlargeUnderstanding palliative care, contextualizing goals, and mastering how to treat incurable disease is highly relevant but understudied in almost every subspecialty in otolaryngology. It is thus clear that a structure is necessary from which to approach difficult patients in a compassionate and ethical manner.

Beauchamp and Childress have extolled principlism, the most common method of reasoning in contemporary clinical ethics. In particular, as surgeons offering interventions to patients, we consider beneficence (Will the intervention benefit the patient?), autonomy (What does the patient want?), nonmaleficence (Will the intervention cause harm?), and justice (Is the intervention a good use of limited resources?). Of course, complicated cases involve overlapping and conflicting principles.

Consider the following case. A 69-year-old man with locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer was treated with chemoradiation and presents to your clinic for post treatment follow-up. He did not tolerate treatment well and missed a number of treatments due to poor social support/financial issues. Your examination is concerning for persistent disease. Subsequent imaging shows widely metastatic, unresectable disease. Upon telling him this information, the patient tearfully looks you in the eye and asks, “Doc, am I going to die?”

Very few of us would feel comfortable in this situation. But there are some general principles that will help guide the discussion. First, it is important to understand if patients are asking an emotional question or a knowledge question. If a patient is asking an emotional question, the correct answer is not to answer without addressing the real question the patient is asking. Rather, open-ended questions about what the patient’s individual goals are can be helpful: What are you most worried about? What are you hoping for? What is most important to you? What are you thinking about right now? Patients often have difficulty describing what is really important until they are explicitly asked. Commonly described goals are to prolong life, minimize pain, and maintain independence, but clarifying what this means to the patient will clarify the decision-making process. In addition, not every decision needs to be made in real-time, and giving patients/families time to think about their goals is often necessary. This can be difficult for surgeons who are trained to quickly identify and provide a fix to problems, but giving this additional time may lead to a better long-term outcome over the illness trajectory.

Occasionally even after a clarifying conversation, patients, such as the one described in the vignette, may nonetheless ask you to attempt surgery. But we must be clear about what surgery can and cannot accomplish. Palliative surgery may include tracheostomy for airway obstruction or gastrostomy for nutrition access and offering these as options is part of best care practices to address discrete goals. Major surgery in the context of incurable disease, however, may have disproportionate risk. Surgeons must also be clear that choosing not to operate does not mean that they are abandoning the patient, or that there are no adjunctive or alternative treatment options. It is incumbent for surgeons to continue to care for patients even if surgery is not warranted, wanted, or feasible.

For patients with advanced head and neck malignancy or other incurable disease, palliative care consultation is recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, as significant evidence exists that there is increased survival and quality of life with upstreaming palliative care. Palliative care is defined as supportive care designed to improve quality of life and treat symptoms. This can be as simple as giving an ibuprofen for pain, or as complex as targeted radiation therapy. Palliative care does not preclude patients from receiving treatment for their underlying disease, and it should be clear that it is not “giving up,” but often improves both quality and quantity life. For example, in one study in patients with inoperable lung cancer, patients randomized to early palliative care consultation had improved survival and quality of life compared to patients randomized to standard of care chemotherapy without palliative care consultation.1 As Atul Gawande writes, “If palliative care were a cancer drug, if it were a pill, it would be a blockbuster company, and we’d all want stock in it.” Understanding what palliative care entails is thus something that all otolaryngologists should understand and be able to explain.

Despite evidence that palliative care is highly beneficial to patients nearing the end of life, barriers to access are significant. These include economic barriers such as a lack of gas money to make it to appointments, loss of work, and comparatively low reimbursement for palliative services. Other barriers include a lack of support systems and a persistent misunderstanding by many physicians that palliative care consultation is tantamount to “giving up.” Training for otolaryngology residents and fellows to provide end-of-life care is also limited, though there are efforts to improve training paradigms. The American Society for Head and Neck Surgery recently included palliative care as a core competency for fellowship, and the American College of Surgeons has introduced a resident’s guide for palliative care. But widespread dissemination of this information remains aspirational.

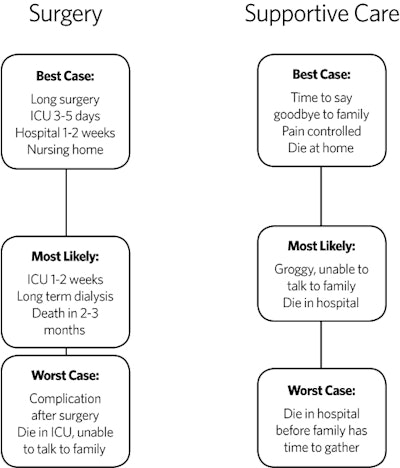

Having a systematic way to approach difficult conversations may be a way to improve care at the end of life. If physicians have a well-trodden path, they will feel more comfortable bringing up these topics, which is a service to our patients and their families. Thus, a decision tool such as the one shown is quite helpful when discussing treatment options in patients with poor prognosis.2 When discussing two alternative options, each option should have the “best case, worst case, and what the physician feels is the most likely case” discussed, and this should be drawn on a sheet so patients can easily visualize their decisions in a head to head manner. This allows frank, realistic discussions about expectations, is expedient, and allows patients to have something to hold onto after the physician leaves.

To close, a quote from Atul Gawande’s “Being Mortal” sums up how we should think about palliative care as otolaryngologists. “We think our job is to ensure health and survival. But really it is larger than that. It is to enable well-being. And well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive.”

1. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733-42.

2. Kruser JM, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, Brasel KJ, et al. “Best Case/Worst Case:” Qualitative Evaluation of a Novel Communication Tool for Difficult in-the-Moment Surgical Decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(9):1805-11.