Richard W. Waguespack, MD, Discusses Revised Clinical Indicators

In the dozen years since the last Clinical Indicators (CIs) for Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery were released, there has been change throughout the practice of medicine. Not the least is the high-speed communication enabled by the Internet. While the 1988 CIs, originated by the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee, might have been written in stone, the current ones reflect instant information. As a result, the Physician Payment Policy (3P) Workgroup, which provides oversight of the CIs, has kept a sharp eye on the accuracy of the list, and has, in fact, pulled some off the website to update them. The new CIs reflect the best-known procedures for the range of medical practices included in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. The Bulletin spoke with Richard W. Waguespack, MD, AAO-HNS Socioeconomic Affairs coordinator and co-chair of 3P, which oversaw the revisions. It was a long process, he noted, to combine “the art of medicine with hardcore evidence,” collecting input from many sources. He emphasized that the clinical indicators are not laws, but are meant to help ease the doctor and payer relationship and secure the best treatment of every individual patient. Simply, what are clinical indicators? Dr. Waguespack: Basically, the clinical indicators define a basis of medical necessity for a range of procedures. The [CIs] initially were generated around 1988 by quality improvement processes at many levels. Their intent is to help practitioners engage in the best practices, reduce errors, and improve value received as much as humanly possible. The clinical indicators are not meant to be cookbooks, but general procedural guides. It becomes a slippery slope defining how exactly one should adhere to the clinical indicators or how precise to make them, but most doctors would adhere closely and base any variance on patient-specific factors. For example, there is a CI for putting tubes in ears, which would outline the amount of therapy and examination findings that would justify placing tubes. But if one had a patient who was intolerant of antibiotics, whose speech was being delayed because of fluid, or had other factors that might make it inappropriate to wait or fulfill all listed criteria, then the doctor would be justified in considering intervening sooner than the CI might suggest. The CIs are not so specific as to lock people into specific management because there are often multiple ways to treat problems and differences between patients. How are CIs developed? Due to the significant socioeconomic implications inherent with publishing CIs, the Academy uses 3P as the steering committee that oversees the process, making sure they reflect current practice. In turn, 3P seeks recommendations from our committees and other interested parties for revisions or new CIs. Our committees provide the medical expertise that underpins the indicators. Occasionally, more than one committee looks at a subject and there is often a need for coordination between specialties and subspecialty societies. While this is the first major revision in 10 or 11 years, we had taken several CIs off our website because there was dated information there. In this major revision, we took the old indicators and prioritized those that were most in need of revision. For example, the Caldwell-Luc indicator was deleted, the determination being that so few of these are done anymore. Although Caldwell-Luc is still a valid procedure for a very small number of people, because of the evolution of endoscopic sinus surgery, it was not reasonable to invest time and resources to update at this time. Fundamentally, we work a great deal by email and with a rigorous back and forth until a good consensus is reached. There is a patient information section at the end of each clinical indicator. How is this information intended to be used? Much of this section’s information would come to the patient during their face-to-face physician encounter or consultation. It’s not a script to follow, but it will act as a guide and reference for pertinent information. It’s also reasonable for a primary care practitioner to be aware of the procedures and use the CI to explain to a patient what he or she might expect when referred to a specialist. Or, if the clinical indicator says it’s reasonable to treat medically, then the doctor can see that he or she may consider treating this patient up to a point, before referring. What are some examples of what turned up or changes that were made? One example is a procedure that helps people with BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo). The Epley maneuver, or canalith repositioning, was not in the old CIs, but seemed a helpful addition since it now has its own CPT code and is a mainstream treatment modality. How are clinical indicators different from the Academy’s policy statements and clinical guidelines/consensus statements? Policy statements are documents that express the Academy’s position on any of a number of issues, ranging from general statements (such as support of a patient’s right to choose their own physician, primary care or specialist) to specific ones (such as defining the number of times sinus surgery patients should be debrided postoperatively). Clinical guidelines are in-depth, evidence-based documents on a specific topic that define how a clinical condition might be evaluated and treated. Their development is based on a comprehensive and generally cross-specialty literature review and is intended to represent state-of-the-art management of that condition. Authors are drawn from a broad base of clinicians. Examples include otitis externa, hoarseness, and sudden idiopathic sensorineural deafness. Consensus statements are similar, but are based more on expert opinion. In contrast, CIs are briefer and are intended to outline the clinical context and rationale for performing certain procedures or services. Associated diagnoses and ICD-9 codes are included, as is a brief description intended for patient education. How do insurers use clinical indicators? Can you give an example of how the clinical indicators have been used by private payers/Medicare to benefit otolaryngologists? I think the overall intent of everyone involved is to engage in the best practices and the majority of insurance carriers are truly trying to do what they perceive is the right thing to serve their clients. But there are inevitably controversies between the doctors’ and others’ perspectives of optimal care. The devil is in the details. If an insurance carrier wants to change its indicators it can, and when they are reasonable, there’s nothing too much to be said. But oftentimes we need to act. In one case, we learned from our members about a major carrier that had changed its indicators on septal surgery. We engaged our subspecialty societies and the plastic surgery society to work on this. This is where the art of medicine is balanced with hardcore evidence. This gets down into the weeds, defining practical medical management. We engaged in a written and phone dialogue to make their requirements to pre-certify the surgery more clinically relevant and medically logical. This was by no means simple and took many weeks to finalize. We then needed to monitor via our membership that the policy was properly implemented. We did not sense this carrier used our then-existing CI for their policy development and we remained mindful of this interaction as the septoplasty CI was revised. Another example relates to sinus surgery wherein a carrier created a precertification policy requiring the patient to have maximum medical therapy before surgery would be approved. The carrier understandably wished to have the doctor treat medically until the point that non-surgical treatment had failed or the patient was having significant disease progression requiring surgical intervention. The definition of maximal medical therapy was a major source of contention and varies from patient to patient, depending on their specific clinical condition. This carrier cited an old, outdated CI to define maximal medical care, so a discussion ensued to update indications. These updates are now incorporated into our revised CI. Is there a way physicians can provide input into the development of future clinical indicators? Doctors can make relevant individual committees aware of the need for new, or revisions to, CIs or directly contact the Academy. Most likely this would be driven by a need encountered in their practice, say to help deal with payers. The committee or 3P would then start the formal process of development. How can a physician use clinical indicators in their everyday practice? Making primary care physicians aware of the CIs should aid their making more appropriate referrals and help their patients begin to understand what to expect and the rationale for recommending these procedures. Otolaryngologists might well consider sending CIs to their referring physicians in this educational manner. What other resources does the Academy have that can help otolaryngologists and head and neck surgeons improve quality? The Academy and the American Board of Otolaryngology are interested in seeing that all practicing otolaryngologists are engaged in lifelong learning. For those of us working on health policies, instruction, and writing articles, it is an obligation both to keep our quality standards high and communicate and disseminate this to our colleagues. Personally, I feel the profession has given a lot to me, and our ongoing job is mentoring younger physicians to assume our positions.

In the dozen years since the last Clinical Indicators (CIs) for Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery were released, there has been change throughout the practice of medicine. Not the least is the high-speed communication enabled by the Internet. While the 1988 CIs, originated by the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee, might have been written in stone, the current ones reflect instant information. As a result, the Physician Payment Policy (3P) Workgroup, which provides oversight of the CIs, has kept a sharp eye on the accuracy of the list, and has, in fact, pulled some off the website to update them. The new CIs reflect the best-known procedures for the range of medical practices included in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. The Bulletin spoke with Richard W. Waguespack, MD, AAO-HNS Socioeconomic Affairs coordinator and co-chair of 3P, which oversaw the revisions. It was a long process, he noted, to combine “the art of medicine with hardcore evidence,” collecting input from many sources. He emphasized that the clinical indicators are not laws, but are meant to help ease the doctor and payer relationship and secure the best treatment of every individual patient.

Simply, what are clinical indicators?

Dr. Waguespack: Basically, the clinical indicators define a basis of medical necessity for a range of procedures. The [CIs] initially were generated around 1988 by quality improvement processes at many levels. Their intent is to help practitioners engage in the best practices, reduce errors, and improve value received as much as humanly possible.

The clinical indicators are not meant to be cookbooks, but general procedural guides. It becomes a slippery slope defining how exactly one should adhere to the clinical indicators or how precise to make them, but most doctors would adhere closely and base any variance on patient-specific factors.

For example, there is a CI for putting tubes in ears, which would outline the amount of therapy and examination findings that would justify placing tubes. But if one had a patient who was intolerant of antibiotics, whose speech was being delayed because of fluid, or had other factors that might make it inappropriate to wait or fulfill all listed criteria, then the doctor would be justified in considering intervening sooner than the CI might suggest.

The CIs are not so specific as to lock people into specific management because there are often multiple ways to treat problems and differences between patients.

How are CIs developed?

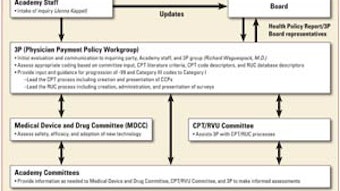

Due to the significant socioeconomic implications inherent with publishing CIs, the Academy uses 3P as the steering committee that oversees the process, making sure they reflect current practice. In turn, 3P seeks recommendations from our committees and other interested parties for revisions or new CIs. Our committees provide the medical expertise that underpins the indicators. Occasionally, more than one committee looks at a subject and there is often a need for coordination between specialties and subspecialty societies.

While this is the first major revision in 10 or 11 years, we had taken several CIs off our website because there was dated information there. In this major revision, we took the old indicators and prioritized those that were most in need of revision. For example, the Caldwell-Luc indicator was deleted, the determination being that so few of these are done anymore. Although Caldwell-Luc is still a valid procedure for a very small number of people, because of the evolution of endoscopic sinus surgery, it was not reasonable to invest time and resources to update at this time.

Fundamentally, we work a great deal by email and with a rigorous back and forth until a good consensus is reached.

There is a patient information section at the end of each clinical indicator. How is this information intended to be used?

Much of this section’s information would come to the patient during their face-to-face physician encounter or consultation. It’s not a script to follow, but it will act as a guide and reference for pertinent information. It’s also reasonable for a primary care practitioner to be aware of the procedures and use the CI to explain to a patient what he or she might expect when referred to a specialist. Or, if the clinical indicator says it’s reasonable to treat medically, then the doctor can see that he or she may consider treating this patient up to a point, before referring.

What are some examples of what turned up or changes that were made?

One example is a procedure that helps people with BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo). The Epley maneuver, or canalith repositioning, was not in the old CIs, but seemed a helpful addition since it now has its own CPT code and is a mainstream treatment modality.

How are clinical indicators different from the Academy’s policy statements and clinical guidelines/consensus statements?

Policy statements are documents that express the Academy’s position on any of a number of issues, ranging from general statements (such as support of a patient’s right to choose their own physician, primary care or specialist) to specific ones (such as defining the number of times sinus surgery patients should be debrided postoperatively). Clinical guidelines are in-depth, evidence-based documents on a specific topic that define how a clinical condition might be evaluated and treated. Their development is based on a comprehensive and generally cross-specialty literature review and is intended to represent state-of-the-art management of that condition. Authors are drawn from a broad base of clinicians. Examples include otitis externa, hoarseness, and sudden idiopathic sensorineural deafness. Consensus statements are similar, but are based more on expert opinion. In contrast, CIs are briefer and are intended to outline the clinical context and rationale for performing certain procedures or services. Associated diagnoses and ICD-9 codes are included, as is a brief description intended for patient education.

How do insurers use clinical indicators? Can you give an example of how the clinical indicators have been used by private payers/Medicare to benefit otolaryngologists?

I think the overall intent of everyone involved is to engage in the best practices and the majority of insurance carriers are truly trying to do what they perceive is the right thing to serve their clients. But there are inevitably controversies between the doctors’ and others’ perspectives of optimal care. The devil is in the details.

If an insurance carrier wants to change its indicators it can, and when they are reasonable, there’s nothing too much to be said. But oftentimes we need to act. In one case, we learned from our members about a major carrier that had changed its indicators on septal surgery. We engaged our subspecialty societies and the plastic surgery society to work on this. This is where the art of medicine is balanced with hardcore evidence. This gets down into the weeds, defining practical medical management. We engaged in a written and phone dialogue to make their requirements to pre-certify the surgery more clinically relevant and medically logical. This was by no means simple and took many weeks to finalize. We then needed to monitor via our membership that the policy was properly implemented. We did not sense this carrier used our then-existing CI for their policy development and we remained mindful of this interaction as the septoplasty CI was revised.

Another example relates to sinus surgery wherein a carrier created a precertification policy requiring the patient to have maximum medical therapy before surgery would be approved. The carrier understandably wished to have the doctor treat medically until the point that non-surgical treatment had failed or the patient was having significant disease progression requiring surgical intervention. The definition of maximal medical therapy was a major source of contention and varies from patient to patient, depending on their specific clinical condition. This carrier cited an old, outdated CI to define maximal medical care, so a discussion ensued to update indications. These updates are now incorporated into our revised CI.

Is there a way physicians can provide input into the development of future clinical indicators?

Doctors can make relevant individual committees aware of the need for new, or revisions to, CIs or directly contact the Academy. Most likely this would be driven by a need encountered in their practice, say to help deal with payers. The committee or 3P would then start the formal process of development.

How can a physician use clinical indicators in their everyday practice?

Making primary care physicians aware of the CIs should aid their making more appropriate referrals and help their patients begin to understand what to expect and the rationale for recommending these procedures. Otolaryngologists might well consider sending CIs to their referring physicians in this educational manner.

What other resources does the Academy have that can help otolaryngologists and head and neck surgeons improve quality?

The Academy and the American Board of Otolaryngology are interested in seeing that all practicing otolaryngologists are engaged in lifelong learning. For those of us working on health policies, instruction, and writing articles, it is an obligation both to keep our quality standards high and communicate and disseminate this to our colleagues. Personally, I feel the profession has given a lot to me, and our ongoing job is mentoring younger physicians to assume our positions.