(How) Can We Influence Our Future? Part I

When irrefutable evidence about the costs of providing care to patients fails to move the needle, one must ask, can we influence our future?

James C. Denneny III, MD

James C. Denneny III, MD

AAO-HNS/F Executive Vice President and CEO

When I first accepted the EVP/CEO position, I was trying to encapsulate just how the organization could best serve its members and the specialty in a short, overarching phrase that could steer us through rapidly changing times and identify what we needed to do to accomplish this goal.

“Provide otolaryngologists with the tools they need to provide the best patient care” was simple, yet comprehensive and led to the creation of a portfolio of assets that I believed would be valuable to have when reform of the healthcare delivery system finally began. Delays and “patchwork fixes” to the system we have dedicated our lives to have added additional complexities that must be acknowledged and considered moving forward. I have modified the original concept to be a more descriptive, current goal for the Academy.

“Provide otolaryngologists with the tools they need to provide the best care to their patients equitably and sustainably in an environment that maximizes efficiency and removes the systemic barriers and unnecessary stress physicians face while fostering the joy that comes from successfully helping patients.”

What will otolaryngology need to be a meaningful contributor when the United States takes healthcare reform seriously? The following five elements are essential in my mind, and I will cover the first two in depth in this column:

- Foundational excellence

- Adequate access to care and services

- Outcomes data defining “best care”

- Collaboration across the specialty

- Allies and partners within medicine and more broadly in the ecosystem of patient care

Foundational Excellence

Foundational excellence is the basis that gives otolaryngologists the platform necessary to justify the lofty position we hold in the house of medicine related to diagnosis and management of the disease processes defined by our education and training. Defining the specialty is important, but it is equally important to identify who is qualified to call themselves an otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon. Following graduation from a qualified medical school, completion of a residency program in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery is required. During residency, both comprehensive didactic and clinical education across the breadth of the specialty is integral to the overall training experience. The AAO-HNSF has been deeply involved in creating resources for resident education for decades.

Over the last six years, we have generated the outline of an otolaryngology-head and neck surgery core curriculum, replaced the venerable Home Study Course with our Focused Lifelong Education Xperience (FLEX), which includes eight specialty topics per year developed by 180 Foundation education experts and presented in a variety of creative and contemporary learning modalities. We will be rolling out a game-changing new product, the Otolaryngology Core Curriculum (OCC) this summer, which introduces a standardized, unified curriculum to support otolaryngology residents in training so that all will have access to an equal didactic experience across all residency programs. This product will also provide value to practicing otolaryngologists and their staff as well as advanced practice providers who work in the specialty. The AAO-HNSF also plans to make the OCC part of its global education strategy, particularly for underresourced countries around the world.

It is important not only to complete rigorous education and training programs, but also to have some mechanism to validate the competency needed to transfer that knowledge to real-world treatment of patients. Following completion of an American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) residency program in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, graduates are eligible to be examined for certification by the American Board of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery on all aspects of the specialty. Board-certified otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons have completed exceptional training and verified competence through a comprehensive certification program.

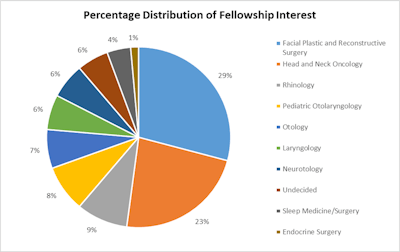

After completing their Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-approved residency program, some otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons choose to do an additional fellowship in areas of their particular interest. In our recent 2023 Workforce Survey, 49% of the participants indicated they have completed a clinical fellowship following residency in one of the 11 subspecialty areas of otolaryngology. For many of these subspecialties, there are additional examinations for sub-certification and focused practice designation.

The third leg of the stool involves demonstrating the same competence and skill through treating patients in real world situations. In the U.S., state medical boards, hospital and surgery center privileging committees, and ABMS Boards oversee physician efforts to maintain and enhance competency through lifelong learning activities such as CME materials and events, additional training on new technology, and maintenance of certification.

Otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons have access to and widely participate in education opportunities to maintain the skills and knowledge that create our “foundational excellence” necessary to be an asset for patients in any version of healthcare delivery reform.

Adequate Access to Care

Otolaryngology will need to be able to provide adequate access to our portfolio of services to all patient populations, including the underrepresented and underresourced areas across the country or risk encroachment by both physician and nonphysician providers. Currently, we face repeated attempts by nonphysician provider groups to expand their scope of practice, not by training or education, but promoting this change as a solution for access problems that patients are experiencing in specific areas of practice. COVID-19 highlighted this issue and temporary relaxation of standards of care in favor of access have emboldened these groups to ask for even more privileges that can significantly affect patient safety. The fact that requested changes would have no significant impact on access does not seem to resonate with either the requesters or legislative bodies. This move signifies an underlying choice of access over quality that we must resist. The real solution should be guided by appropriate and affordable access and not compromise patient outcomes or safety.

Identifying solutions for this problem also requires a systematic evaluation of resources needed to provide an acceptable level of access to as many as feasible while still maintaining the quality of the service they receive. An accurate assessment of the otolaryngology-head and neck surgery resources is the starting point for this discussion. The Academy conducted an extensive Workforce Survey in 2022 and 2023 to try to get accurate information on the composition and location of our current workforce assets as well as indications on future trends that might alter the current situation.

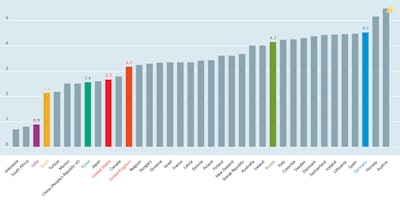

There has been discussion for years as to the appropriate number of physicians overall and specialists that are required to properly serve distinct populations. Typically, this has been expressed as the number of physicians per capita (1,000 people). The graph below from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) represents the total number of physicians per 1,000 inhabitants in each of the countries below at 2022 year-end.1

Reproduced from OECD (2024), Doctors (indicator). DOI: 10.1787/4355e1ec-en (Accessed on 12 March 2024).

Reproduced from OECD (2024), Doctors (indicator). DOI: 10.1787/4355e1ec-en (Accessed on 12 March 2024).

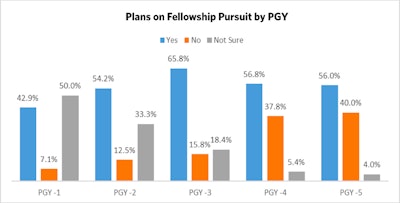

Historical studies over the last two decades have estimated that there are between 0.3 – 0.35 otolaryngologists per 1,000 people in the U.S. Our 2022 Workforce Study estimated that by 2025 that would be 0.36 per 1,000 people but acknowledged the difficulty in getting to an exact accounting of practicing otolaryngologists in the U.S. It is critical to understand both the current and future workforce dynamics to help create plans to expand access to otolaryngology services in a way that fills in the existing gaps with quality care. Equally as important as the total number of otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons is where they are located and how they’re going to use their fellowship training. Data from the 2023 Workforce Survey indicated that over half of the PGY-5 residents planned to pursue a fellowship, as seen below:

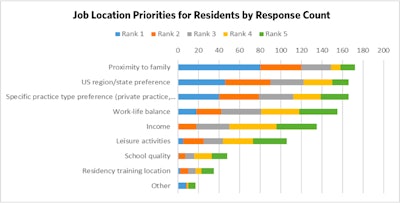

Following the completion of residency training with or without a fellowship, the major priorities in choosing a job location are listed below:

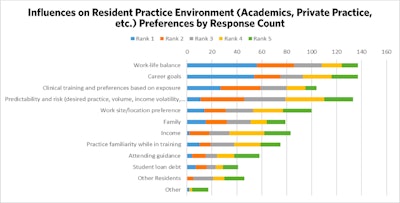

Factors that were most important for resident selection of a practice environment (academic, private practice, employed, etc.) are detailed below:

The two most important priorities for job location were proximity to family and U.S. region or state preference. It will be important to continue to follow analyses like these in planning how to adequately address providing care to currently underserved areas. It is very clear that there will be certain regions or types of locations that will be difficult to provide the volume of otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons to meet existing definitions of adequate care. This combination of preferences indicates that it will be difficult to induce physicians to locate in currently underserved areas unless there are family ties or some other inducement.

The rapid embrace of telehealth technology during the COVID-19 pandemic by both government and private payers, patients, and physicians has solidified the use of this technology as a valuable component that will factor into the formation of more integrated networks designed to expand access to areas needing it most due to provider shortages. The popularity of this modality will ensure there will be continued technologic advances that will produce better tools for the examination and management of patients from distant sites from a supervising physician. This creates a wonderful opportunity to develop team-based partnerships with local physicians, advanced practice providers, and other members of the healthcare delivery system who can deliver effective care to areas that most likely will never have local access to the full spectrum of medical care needed by their community.

The time is now to explore nontraditional partnerships with colleagues across the spectrum of healthcare delivery that will expand the capacity and reach of the otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon that would be otherwise impossible. If properly designed, patients can still receive high-quality, data-driven care through these partnerships with comparable outcomes to the rest of the system.

This model has great potential for otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons as well as most of the medical community. To maximize the benefit of programs like this, it is essential that the overall system undergoes a major redesign that maximizes the physician’s patient-facing time and eliminates administrative burden that is not effective in improving outcomes of the care delivered. There is an extensive list of seemingly minor obstacles that are persistently added over time that result in a significant decrease in the number of patients a physician can see daily. If these “add-ons” improved outcomes, there could be some justification for the inclusion of some of them. In reality, they are weakening our healthcare delivery system through inefficiency and waste.

In the upcoming April EXTRA, I will address how outcomes data defining “best care” will be an essential element of the healthcare delivery system in the future, how collaboration across the specialty as well as throughout the house of medicine will be critical to maintaining the physician’s role as leader of healthcare delivery teams, and how to find allies and partners throughout the ecosystem of patient care. If we accomplish the first five elements listed at the beginning of this column, it will take advocacy excellence to put it all together into packages that we can promote to those in charge of healthcare system reform with a chance to succeed.

Reference

OECD (2024), Doctors (indicator). DOI: 10.1787/4355e1ec-en (Accessed on 14 March 2024)