Professionalism and Well-being

Professionalism has been one of the pillars at the heart of the practice of medicine for centuries.

James C. Denneny III, MD

James C. Denneny III, MD

AAO-HNS/F EVP/CEO

A number of institutions, organizations and specialties have also created their respective versions of these principles that further emphasize desired points specific to their situations.

The initial teaching and learning of these principles are critical to the preservation and advancement of the medical profession, particularly during times of societal change and the ongoing alteration of the healthcare delivery system we are currently undergoing. Rightfully, this has been a major focus of medical education for both medical students as well as residents and fellows. Didactic and observational learning has proven valuable in developing an understanding how to formulate one’s own guiding principles that will grow with experience. Professionalism should be considered an integral part of lifelong learning just as clinical and scientific advances are. The relatively rapid and accelerating change in many areas of the “professionalism charter” make it imperative that physicians remain current with evolving standards.

There have been many publications linking wellness and professionalism. The relationship between stress and professional behavior in both individuals and teams is well documented. Periods of extreme stress, anxiety, and burnout can leave individuals more susceptible to lapses in professional behavior. It is inevitable that all individuals will experience repetitive periods of exacerbated stress that will need to be mitigated by healthy coping mechanisms. Learning effective ways of coping, both through training and individual experience, is crucial for all age groups of physicians, but particularly those beginning their careers in medicine. Mindfulness is a valuable tool in managing stress both in the personal and professional settings that physicians find themselves in. It is very clear that uncontrolled stress can lead to unprofessional behavior that an individual would not typically exhibit as everyday behavior.

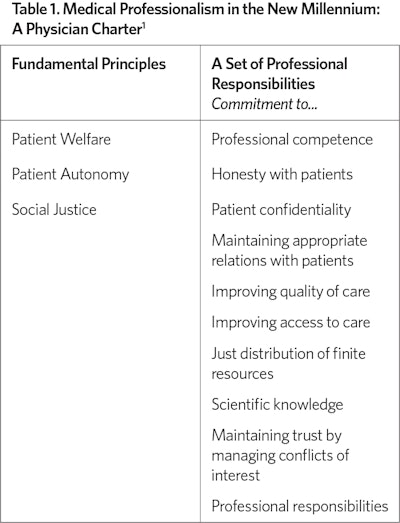

I have described a well-intentioned, absolutely essential focus on professionalism for both trainees and practicing physicians and the negative effect stress has on behavior. I have great concern that this focus on “professionalism” constitutes a potential significant trigger that increases stress and decreases well-being. The rapid change in knowledge and technical skills needed as well as acceptable social norms often leave physicians struggling internally with common decisions. A quick review of the 10 responsibilities listed in Table 1 reveals that physicians are often asked to do things that they are not adequately trained for, particularly in societal issues outside of the scope of medicine. Another area that tends to stress professionalism is current payment methodology, particularly when based entirely on relative value units. Questionable physician professional behavior is now commonly treated and investigated like physician impairment. There is also an increasingly unfortunate association between professionalism and a “disruptive behavior” label, when in fact behavior issues constitute only one area of professionalism.

The drive to be the perfect, consummate professional undoubtedly contributes considerable anxiety and stress during certain situations where societal norms are in constant flux and not universally agreed upon. We are undergoing a significant societal upheaval and cultural change in the United States and healthcare delivery that means different things to different people. Hopefully, in this era of “one strike” you are labeled, we can promote professionalism as something to be valued and not feared. This will require effort, flexibility, willingness to learn, and tolerance broadly.

References

1. ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine; ACP-ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Feb 5;136(3):243-6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. PMID: 11827500.