The Manifestations of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in Ear, Nose, And Throat, Head And Neck

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak is a public health emergency of significant international concern. The World Health Organization estimates we will see more than 10,000 new Ebola cases each week in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia by the end of the year.

Segun-Segun Busari, MD; University of Ilorin Nigeria

Tulio Valdez, MD; Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT

Farrel J. Buchinsky, MBChB; Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, PA

Titus S. Ibekwe, FWACS, FMCORL; University of Abuja Teaching Hospital Abuja Nigeria

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak is a public health emergency of significant international concern. The World Health Organization estimates we will see more than 10,000 new Ebola cases each week in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia by the end of the year. A total of 25 outbreaks with mortality ranging 25 percent to 100 percent have been documented since the identification of the EVD in 1976. The virulence and transmissibility level of EVD is at an exponential rate of up to eight people getting infected by a single uncontrolled case and this rate doubles within 20 days. These outbreaks were mostly contained to Africa until 2014 when the worst epidemic is being witnessed in West Africa with imported cases in Europe and America and most recently with healthcare workers being infected in Spain and the United States despite precautions.

Despite all efforts and technological advancements toward therapy, there is no proven cure for EVD. Supportive treatment/fluid-replacement therapy, prevention, and control remain the only known interventions.

The mode of presentation of EVD could be deceptive and mimics common illnesses like influenza, pharyngotonsilitis, and infective rhinitis as well as other conditions more commonly seen in Africa, such as malaria, typhoid fever, and Lassa fever. It presents with common otolaryngological symptoms like rhinorrhea, sore throat, epistaxis, and other constitutional symptoms of fever, headache, and malaise.

It is unlikely that an undiagnosed person with EVD will present to an otolaryngologist, but not impossible.

Furthermore, it is possible that an otolaryngologist could be consulted on a patient with epistaxis and where the previous medical staff have not established a travel history.

To this end it is important to triage the patients and ask for any recent travel to the affected areas or if they have been in contact with someone who recently traveled to one of the affected areas.

The Infectious Disease Committee of the AAO-HNS through its International Members from West Africa and United States has categorized the ENT manifestations of the EVD for the sensitization/education of its Members globally.

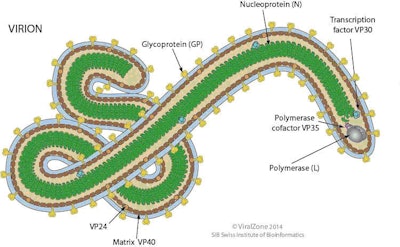

Figure 1: Geography of Ebola Virus (Filoviridae family). Written permission was secured from the Viralzone, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (11/19/2014) for the use of the above figure in illustrating the special features of the Ebola Virus.

Figure 1: Geography of Ebola Virus (Filoviridae family). Written permission was secured from the Viralzone, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (11/19/2014) for the use of the above figure in illustrating the special features of the Ebola Virus.The West African sub-region has been severely affected by EVD, especially Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia. These three countries have not been able to contain the disease. As of November 2014, the other 51 countries on the African continent are Ebola free. Two of the 51 countries, Senegal and Nigeria, both in West Africa, had successfully contained EVD and certified Ebola free by the WHO on 17th and 20th October 2014 respectively. The two classes of countries, contained and not contained, should serve as the world’s case studies on the impediments against and factors for the eradication of this disease. The United States of American Health Agencies are collaborating with the Nigerian Health Authorities toward understudying the method deployed by this nation of more than 170 million in containing and eradicating the EVD brought to Nigeria by a Liberian diplomat. It is of utmost importance that identification of a single case should be managed with the recognition as having the potential to be the start of an epidemic. The cases seen outside Africa serve as a reminder that no nation can live in isolation; trans-border movements, commerce, trade and collaborative relationships among nations cannot be segregated from the existence and growth of the global economy. Hence a total containment of EVD within the identified endemic areas remains a priority although still a herculean task.

The Nigerian Response to the Crisis

The steps taken that lead to the Nigerian success included a quick declaration of the EVD as a disaster by the Nigerian government and massive mobilization of resources toward it. Mass mobilization and sensitization of the public and the entire citizenry of Nigeria including those in the hinter lands through the various arms of government, opinion leaders, religious leaders and importantly the health workers were quite useful. Demystifying the disease to discourage attrition via global and holistic campaign against the “myths” surrounding EVD, deployment of the telecommunication apparatus especially the cellular networks and telephone operators in disseminating unsolicited messages regularly to all subscribers on “facts and fictions” surrounding EVD (bearing in mind that at least 70 percent of the population had access to this media and the mass media) proved efficacious. Modification in life styles and rituals to discourage the spread of EVD in religious houses/place of worships, homes, and villages were enforced through the leaders and voluntary organizations. Ebola hotlines were created and wide publicity created around the country including the establishment of some Ebola centers where primary and secondary contacts including people down with the disease were effectively quarantined for monitoring and/or therapy. Furthermore, the selfless volunteerism by Nigerian medical doctors and other health workers toward serving in Ebola designated centers were quite helpful. In such instances, there was never a shortage in the number of the volunteer health workers needed to offer services in such centers. The rate limiting step was rather the number of Personal Protective Equipments (PPEs) available. Government announced health insurance and remuneration packages to further encourage the volunteer health workers. These measures and more were adopted to make EVD “everyone’s business in Nigeria” within the three months of fight against the containment, treatment of survivors, and total eradication of the disease in the country.

On the contrary, discrimination, stigmatization, and tenacious adherence to some inimical cultural practices, poor and non-prompt response by the Global Health bodies (e.g. UN), among others had been identified as factors affecting the prompt containment and eradication EVD in other neighboring countries.

The Clinical Features of EVD Mimicking ENT, Head and Neck Diseases

Health workers are prone and vulnerable to contracting this disease especially those in emergency services units, general practitioners, pediatricians, and geriatricians. In as much as some disciplines such as otorhinolaryngology may not be as exposed to EVD compared to the former, all the health workers operate within the same health facilities and environments. Furthermore, the modes of presentations of EVD can mimic lots of ORL diseases (Table1) and therefore the need for caution. Every health worker must be acquainted with the modes of presentation and transmissibility of EVD.2

| Ebola Virus Disease Clinical features | Common ENT & Head and Neck manifestations | Common differentials |

|

Headache, fatigue, sore-throat, rhinorrhoea, myalgia, fever. | Influenza, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, infective rhinitis. malaria, rhino sinusitis, typhoid fever, Lassa fever. |

|

High fever, +/- rashes, vomiting & hematemesis, passive behavior, bruising, brain injuries, epistaxis, hematemesis, red eyes, bleeding from eyes and the other orifices. | Epistaxis, measles, rubella, chicken pox, cholera, shigelosis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC). |

|

Massive dehydration and loss of consciousness, seizures, massive internal hemorrhage, multiple organ failures especially renal and hepatic, death. | Head Neck malignancies, lymphoproliferative disorders, HIV, distant metastasis from unknown primaries. |

| Table1: Ebola viral disease and common ENT, Head and Neck manifestations. The classification of the EVD manifestations according to days of disease establishment was partly adapted from the CDC. However, it is worthy of note that the presentations of EVD do not strictly follow the above order. The manifestations are often erratic and fail to follow a clearly demarcated pattern. Factors like the strain of EBV, virulence, patient’s immune status, levels of supportive healthcare, etc. are determining factors. | ||

Early in its course EVD mimics common illnesses like influenza-hence its presentation with flu-like symptoms. The typical malaise, myalgia, initial low fever, and sore throat could be misdiagnosed for pharyngotonsilitis. Bleeding from the nose and oropharynx (although usually late) could present to an ENT surgeon as a case of epistaxis awaiting full investigation and treatment. Infective rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, bleeding disorders as well as other conditions more commonly seen in Africa such as Malaria, Typhoid fever, and Lassa fever would be considered in the differential diagnosis. Head and neck malignancies and advanced cases of cancers with distant metastasis also share similar clinical features with the late phase of EVD as highlighted in table 1.

Basic Safety Measures for ENT Surgeons and Health Workers Against EVD

Principally, every ENT surgeon and indeed all healthcare personnel should make conscious effort to obtain detailed travel history of patients encountered in the clinic and consciously probe on the clinical features of other sick people encountered by the patients within the last 21 days.

A cross-check of the patients’ temperature using the non-contact infrared thermometer before examination is also encouraged. Indeed prompt triaging and invitation of the disease surveillance and infectious disease team to investigate every suspect case and all primary and secondary contacts should be ensured.

There is need to provide and enforce the observation of functional and customized protocols for each health institution — not just for EVD, but for all infectious diseases. Beyond testing suspected samples for EV, there is need to expand frontiers for testing of other common hemorrhagic fever illnesses (emerging and re-merging) to avoid being taken unawares.

Again, every surgeon and indeed operating room personnel (nurses, technicians, and anesthesia staff) are predisposed through surgical operations to such undetected, suspected, or confirmed patients and hence the need to understudy the already outlined EVD surgical protocols of the American College of Surgeons3,4 by all concerned. Availability of personal protective equipment, perfection of the donning and doffing technique, of operating under protective equipment via simulators prior to attending to such suspected or confirmed patient(s) are recommended.

Above all, our consciousness should be aroused to the high probability of an early case being misdiagnosed and therefore the application of primary personal and sanitary hygiene measures before and after attending to each patient in accordance with universal precaution principles.5 On the other hand, outside of an Ebola-affected country and absent such a travel history, the probability that patient has Ebola is exceedingly low.

Every doctor and health worker should remember always that all efforts and technological advancements toward therapeutic cure for EVD had been abortive and therefore supportive treatment/fluid-replacement therapy, prevention, and control remain the only known intervention.

Finally, the divide between protection of the health workers and the violation of patients’ rights can be a thin line. As observed recently, extreme measures such as quarantine and stigmatization of all individuals/visitors from EVD areas could be counterproductive leading to high attrition rates of suspected cases/contacts and even litigations. (www.cbsnews.com/news/ebola-fear-causes-stigma-agaist-west-aficans-in-u-s/) .6,7 To this end, we advise that rules and regulations regarding the control of EVD should conform with the UN and WHO observances.

REFERENCES:

- WHO: New Ebola Cases Could Be Up To 10,000 Per Week In 2 Months. The Huffington Post. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/transmission/human-transmission.html. Accessed 11/11/2014.

- www.facs.org/ebola/surgical-protocol . Accessed 11/11/2014.

- Wren SM, Kushner AL. Surgical Protocol for Possible or Confirmed Ebola Cases. American College of Surgeons; www.facs.org/ebola/surgical-protocol 10/21/2014. Accessed 11/11/2014.

- Siegel JD , Rhinhart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L etal. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. CDC. www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html. Accessed 11/11/2014.

- www.cbsnews.com/news/ebola-fear-causes-stigma-agaist-west-aficans-in-u-s/http://www.cbsnews.com/news/ebola-fear-causes-stigma-agaist-west-aficans-in-u-s/. Accessed 11/11/2014.

- Botelho G, Hanna J. Maine, Nurse at Odds Over Ebola Quarantine. CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/10/29/health/us-ebola/. Accessed 10/29/2014.