Clinical Practice Guideline: Improving Voice Outcomes after Thyroid Surgery (a Summary)

Sujana S. Chandrasekhar, MD; Gregory W. Randolph, MD; Michael D. Seidman, MD; Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH; Peter Angelos, MD, PhD; Julie Barkmeier-Kraemer, PhD, CCC-SLP; Michael S. Benninger, MD; Joel H. Blumin, MD; Gregory Dennis, MD; John Hanks, MD; Megan R. Haymart, MD; Richard T. Kloos, MD; Brenda Seals, PhD, MPH; Jerry M. Schreibstein, MD; Mack A. Thomas, MD; Carolyn Waddington, MS, FNP, CORLN; Barbara Warren, PsyD, Med; and Peter J. Robertson, MPA. This month, the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) publishes its latest clinical practice guideline focusing on improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery as a supplement to Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. This month’s journal and a copy of the guideline are now available at http://oto.sagepub.com/. The following summary presents an outline of the guideline; we encourage all interested parties to read the guideline in its entirety. The intent of this offering is to alert members to the availability of this new multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline so that the complexities of the problem can be fully described and understood. The summary provides an introduction to the topic and the purpose of developing the guideline followed by each of the guideline’s key action statements and related action statement profiles. For more information about the AAO-HNSF’s other quality knowledge products (clinical practice guidelines and clinical consensus statements), our guideline development methodology, or to submit a topic for future guideline development, visit: http://www.entnet.org/guidelines. Introduction Thyroidectomy (surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland) may be performed for clinical indications that include malignancy, benign nodules or cysts, suspicious findings on fine needle aspiration biopsy, dysphagia from cervical esophageal compression, or dyspnea from airway compression. Other indications for thyroidectomy include multinodular goiter, Hashimoto’s and other types of thyroiditis, and thyromegaly with significant cosmetic compromise. Additional surgery may involve neck dissection or completion thyroidectomy, based on the extent of disease and final pathology results. Surgeons performing thyroidectomy include otolaryngologists and general surgeons. Thyroid surgery rates have tripled over the past three decades. Between 118,000 and 166,000 patients in the U.S. undergo thyroidectomy each year for benign or malignant disease.1 Thyroidectomy is performed on patients of both genders, but more commonly on women. Thyroid cancer is the most common malignancy of the endocrine system, and the cancer with the fastest-growing incidence among women. It is estimated that 36,550 women and 11,470 men (48,020 total) in the U.S. were diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2011,2 with 56,000 projected in 2012.3 Palpable thyroid nodules occur in three percent to seven percent of the population; ultrasound indicates that the actual prevalence of thyroid nodules is up to 50 percent. On fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), five percent of thyroid nodules are malignant and 10 percent are suspicious. FNAB has increased the identification of malignancy in nodules from 15 percent to 50 percent predominantly due to increased detection of small papillary cancers.4 The incidence of thyroid cancer in the U.S. rose from 3.6 per 100,000 in 1973 to 8.7 per 100,000 in 2002—a 2.4-fold increase.5 It is the fifth most diagnosed cancer in women, whom it affects more than three times more commonly than it does men. Although peak incidence is between ages 45 and 49 in women and 65 and 69 in men, thyroid cancer accounts for 10 percent of all malignancies diagnosed in young people between the ages of 15 and 29.6 Mortality from thyroid cancer remains low at 0.5 per 100,000.5 The overall numbers of thyroid surgery continue to increase: in 2007, U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) statistics indicated that 37.4 thyroidectomies were performed per 100,000 population. Both increased detection and growing U.S. population (from 281 million in 2000 to 309 million in 2010) enable estimates of thyroid surgery in 2012 of between 118,000 and 166,000. The goals of thyroid surgery remain: complete removal of the abnormal thyroid and any involved lymph nodes, preservation of parathyroid gland function, and maintenance or improvement of voice and swallowing. Reduction in quality of life (QOL) after thyroid surgery is multifactorial, may include the need for lifelong medication, thyroid suppression, radioactive scanning/treatment, temporary and permanent hypoparathyroidism, temporary or permanent dysphonia postoperatively and dysphagia.7-11 Voice disturbance may be identified at least temporarily in up to 80 percent of patients after thyroid surgery, but prevention, evaluation, and management are incompletely defined.8 About one in 10 patients experience temporary laryngeal nerve injury after surgery with longer-lasting voice problems in up to one in 25.12 Although temporary hoarseness is not uncommon in any surgery that involves general anesthesia, the potential for laryngeal nerve injury in thyroid surgery mandates greater concern when hoarseness occurs after this type of procedure.13 The most common site of injury is damage to one or both recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN), which are close to the thyroid gland and are the main nerves that control vocal fold mobility. The other nerves of major interest, and frequently less directly addressed during thyroid surgery, are the bilateral superior laryngeal nerves (SLN), injury to which can impair the ability to change pitch and reduce voice projection.14 Another less common surgical cause for post-thyroidectomy voice change is cervical strap muscle injury.15,16 Non-surgical causes may include laryngeal irritation, edema, or injury from airway management.9 Between 1993 and 2007 the performance of total (over partial) thyroidectomy more than doubled to nearly 40 percent of cases, and that will continue to grow.17 Total (or bilateral) thyroidectomy puts twice the number of SLNs and RLNs at risk. This clinical practice guideline (CPG) seeks to provide guidance to minimize post-thyroidectomy voice impairment in the setting of the increasing number and extensiveness of thyroidectomies being performed by diversely trained and experienced surgeons. This document is intended for all clinicians who diagnose or manage adult patients with thyroid disease for whom surgery is indicated, contemplated, or has been performed. Key terms used in this guideline are as follows: Thyroidectomy is defined as a surgical procedure performed to partially or completely remove the thyroid gland. This term may include total thyroidectomy, or partial thyroidectomy, which includes subtotal thyroidectomy and hemithyroidectomy. Voice outcomes include the patient’s own perceptions of their vocal quality, the perceptions of others, and objective voice-related measurements. Vocal folds, also known as the vocal cords, are twin infoldings of mucous membrane covering the upper surface of each vocalis (or thyroarytenoid) muscle, which extend from the midline, anterior attachment to the thyroid cartilage projecting posteriorly to the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage.18 The vocal folds vibrate, modulating the flow of air being expelled from the lungs during phonation. They consist of epithelium and lamina propria overlying the vocalis muscle. Vocal fold mobility disorders as used in this document include paresis or hypomobility, which are synonymous with vocal fold weakness, and paralysis, which is immobility of the fold. Voice impairment can range from aphonia, which is absence of phonation, to dysphonia, which could include persistent or intermittent breathiness, hoarseness, reduced volume, vocal fatigue, and/or pitch change. Although thyroidectomy procedures may be performed in all age groups, this guideline is limited to adults (aged 18 and older). In a review of AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from 2003 to 2004, the majority of adult patients (78.8 percent) undergoing thyroid surgery were between 18 and 64 years old, 17.9 percent were between ages 65 and 79 years, and 3.3 percent were 80 years old or older.19 Purpose As defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), CPGs are “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care, that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.” They are based on a thorough review of the best evidence available at the time of writing, as evaluated by a multi-disciplinary panel with representation by as many stakeholders as possible. CPGs are intended to enhance clinician and patient decision-making by collating current best evidence into an explicit and transparent action plan.20 The purpose of this guideline is to optimize voice outcomes for adult patients aged 18 years or older after thyroid surgery. The target audience is any clinician involved in managing such patients, which includes, but may not be limited to, otolaryngologists, general surgeons, endocrinologists, internists, speech-language pathologists, family physicians and other primary care providers, anesthesiologists, nurses, and others who manage patients with thyroid/voice issues. The guideline applies to any setting in which clinicians may interact with patients before, during, or after thyroid surgery. Children younger than 18 years are specifically excluded from the target population; however, the panel understands that many of the findings may be applicable to this population. Also excluded are patients undergoing concurrent laryngectomy. Although this guideline is limited to thyroidectomy, some of the recommendations may extrapolate to parathyroidectomy as well. Actions considered by the guideline development group (GDG) were broadly classified into laryngeal examination, voice assessment, nerve management, and interventions. The group agreed that voice outcomes could potentially be improved: Preoperatively, with examination of the larynx, baseline preoperative voice assessment, and appropriate counseling and education for realistic expectations; Intraoperatively, with targeted communication among the members of surgical team, proper anesthetic preparation including avoidance of laryngeal trauma during intubation and avoidance of paralytic agents where indicated, surgical techniques geared to optimize voice outcomes by preventing injury as well as by recognizing and managing injury, use of adjuvant medications during surgery, and defining a role for intraoperative nerve monitoring; and Postoperatively, with baseline postoperative laryngeal examination and voice assessment, setting expectations for recovery, knowing when and to whom to refer, and discussion of options for rehabilitation of voice impairment. This guideline is intended to focus on quality improvement opportunities judged most important by the GDG. It is not intended to be a comprehensive guide for managing patients undergoing thyroid surgery. In this context, the purpose is to define useful actions for clinicians, regardless of discipline, to improve quality of care and voice outcomes. Conversely, the statements in this guideline are not intended to limit or restrict care provided by clinicians based on the assessment of individual patients. Although there is evidence to guide management of many aspects of thyroid surgery, there is no evidence-based, multi-disciplinary, CPG that specifically deals with improving voice outcomes. This guideline is warranted because of known practice variations in the care of patients who undergo thyroid surgery and the large impact voice impairment can have on a patient’s QOL and functional health status. STATEMENT 1. BASELINE VOICE ASSESSMENT: The surgeon should document assessment of the patient’s voice once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Establish a baseline, improve the detection of preexisting voice impairment, establish expectations about voice outcomes, educating the patient, facilitates shared decision-making. Prioritize the need for preoperative laryngeal assessment and more in-depth voice assessment. Risk, Harm, Cost: Anxiety, cost of assessment tool, patient and provider time. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: Perception by the GDG of a current underassessment of voice prior to surgery. Intentional Vagueness: The proximity of the assessment to the day of surgery is not specified because there was no consensus among the guideline group and there was no data to support the choice of one time-point over another. The group agreed that any change in voice would warrant a new assessment. Role of Patient Preferences: Selection of assessment methods. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 2A. PREOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPAIRED VOICE: The surgeon should examine vocal fold mobility, or refer the patient to a clinician who can examine vocal fold mobility, if the patient’s voice is impaired (as determined by the assessment in Statement 1) and a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Assess mobility of vocal fold, potential diagnosis of invasive thyroid cancer, influence the decision for surgery, extent of surgery, intraoperative technique, preoperative patient counseling, distinguish iatrogenic from disease-related paralysis/paresis. Risk, Harm, Cost: Misdiagnosis (false positive/ false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: None. Role of Patient Preferences: Limited. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 2B. PREOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL ASSESSMENT OF THE NON-IMPAIRED VOICE: The surgeon should examine vocal fold mobility, or refer the patient to a clinician who can examine vocal fold mobility, if the patient’s voice is normal and the patient has (a) thyroid cancer with suspected extrathyroidal extension, or (b) prior neck surgery that increases the risk of laryngeal nerve injury (carotid endarterectomy, anterior approach to the cervical spine, cervical esophagectomy, and prior thyroid or parathyroid surgery), or (c) both, once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Assess mobility of vocal fold, potential diagnosis of invasive thyroid cancer, influence the decision for surgery, extent of surgery, intraoperative technique, preoperative patient counseling, distinguish iatrogenic from disease-related paralysis/paresis. Risk, Harm, Cost: Misdiagnosis (false positive/false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: Even though the prevalence of preoperative vocal fold paresis is low, the consequence of not knowing this prior to surgery could result in substantial morbidity or mortality. For this reason, the GDG was willing to accept a large number of normal examinations in return for an occasional abnormal finding. Intentional Vagueness: The timing of assessment relative to surgery is not stated to allow clinicians flexibility in decision-making, although the guideline development group agreed that the assessment should take place as close to the surgery as possible. The word suspected is used due to the difficulty of identifying extrathyroidal extension through physical exam and imaging. Role of Patient Preferences: Limited. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 3. PATIENT EDUCATION ON VOICE OUTCOMES: The clinician should educate the patient about the potential impact of thyroid surgery on voice once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, RCTs on the value of patient education in general regarding surgery. Grade C, studies on the incidence of voice impairment following thyroid surgery in particular. Benefit: Facilitate shared decision making, establish realistic expectations, help patients recognize voice changes postoperatively. Risk, Harm, Cost: Anxiety. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: Generalize evidence about the benefits of patient education to this circumstance. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: Patient can decline information. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 4. COMMUNICATION WITH ANESTHESIOLOGIST: The surgeon should inform the anesthesiologist of the results of abnormal preoperative laryngeal assessment in patients who have had laryngoscopy prior to thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Allow anesthesiologist to select proper tube, allow anesthesiologist to optimize airway management, identify potential problems with intubation and extubation, plan postoperative care and monitoring, may prevent anesthetic-related voice disturbance. Risk, Harm, Cost: None. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: The guideline development group felt that even though the recommendation followed best practice there was a perception the action was not universally performed. Intentional Vagueness: Timing of discussion is not specified but should occur before the patient enters the operating room. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 5. IDENTIFYING RECURRENT LARYNGEAL NERVE: The surgeon should identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve(s) during thyroid surgery. Strong recommendation based on a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, RCTs and retrospective cohort studies. Benefit: Optimize voice outcome, protect the RLN, preserve laryngeal function, reduce incidence of RLN injury. Risk, Harm, Cost: Inadvertent RLN injury, extended operative time, false identification of another structure as the RLN. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: Thyroid surgery limited to the isthmus. Policy Level: Strong recommendation. STATEMENT 6. PROTECTION OF SUPERIOR LARYNGEAL NERVE: The surgeon should take steps to preserve the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve(s) when performing thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Preserves vocal projection and high frequencies. Risk, Harm, Cost: May leave superior pole thyroid tissue. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: The steps taken to preserve the nerve are purposefully not specified in the statement to emphasize the important issue is preserving the nerve, which may or may not be identifiable during surgery. Therefore, it is the attention to the nerve that is important. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 7. INTRAOPERATIVE EMG MONITORING: The surgeon or their designee may monitor laryngeal electromyography (EMG) during thyroid surgery. Option based on one RCT and observational studies with a balance of benefit versus harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C. Benefit: Added information regarding neurophysiologic status of the RLN (specifically when the nerve is injured), potential improved accuracy in nerve identification, potentially avoiding transient/temporary nerve. Risk, Harm, Cost: cost of endotracheal tube and probe, capital equipment costs, education of key personnel including anesthesia, nursing, surgeon and technician, misinterpretation (both false positive/false negative), may instill a false sense of security in identifying nerve. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Equilibrium. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Option. STATEMENT 8. INTRAOPERATIVE CORTICOSTEROIDS: No recommendation can be made regarding the impact of a single intraoperative dose of intravenous corticosteroid on voice outcomes in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. No recommendation based on observational studies with limitations and a balance of benefit vs. harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade D, observational studies with concerns over methodology and clinical importance. Benefit: Uncertain effect on short-term voice improvement or shortening the duration of vocal fold paralysis or paresis. Risk, Harm, Cost: Hyperglycemia. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Balance of benefit vs. harm. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: No recommendation. STATEMENT 9. POSTOPERATIVE VOICE ASSESSMENT: The surgeon should document whether there has been a change in voice between two weeks and two months following thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, and prospective, observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, cohort studies on the prevalence and duration of voice changes after thyroid surgery and the underreporting of voice changes if not specifically sought. Benefit: Identification of significant voice impairment and early institution of counseling and/or voice rehabilitation; avoidance of patient anxiety. Risk, Harm, Cost: Cost of assessment tools/examinations. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: The guideline development group believes that post-operative voice assessment is not being performed universally, in the identified time frame. Intentional Vagueness: The documentation time is stated as between two weeks and two months because there is no evidence on the optimal time, but the GDG suggests that the evaluation should be late enough to overcome transient postoperative changes but early enough to allow effective intervention. Role of Patient Preferences: No role in documenting the outcome, but a significant role in the choice and extent of outcome assessment. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 10. POSTOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL EXAMINATION: Clinicians should examine vocal fold mobility or refer the patient for examination of vocal fold mobility in patients with a change in voice following thyroid surgery (as identified in Statement 9). Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, QOL data, early intervention data, diagnostic maneuver. Benefit: Detect nerve injury, gain information regarding prognosis, institute rehabilitation as needed. Risk, Harm, Cost: misdiagnosis (false positive/ false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety, by restricting this recommendation to only patients with a voice change some nerve injuries may be missed. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: The timing of the examination is not specified, but should occur expeditiously after the identification of a voice change, as identified in Statement 9. Role of Patient Preferences: Moderate, based on patient self-perception of voice postoperatively, based on type of examination of larynx, based on physician determination and patient consent. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 11. OTOLARYNGOLOGY REFERRAL: The clinician should refer a patient to an otolaryngologist when abnormal vocal fold mobility is identified after thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, before- and after- studies showing voice improvement after surgical intervention. Benefit: Awareness of the opportunities for early surgical intervention, confirmation of the laryngeal findings, determination of appropriate treatment plan, facilitates shared-decision making, facilitates coordination with speech-language pathologist in care of patient. Risk, Harm, Cost: Cost, time, access. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: None. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: None. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. STATEMENT 12. VOICE REHABILITATION: Clinicians should counsel patients with voice change or abnormal vocal fold mobility after thyroid surgery on options for voice rehabilitation. Recommendation based on systematic reviews and observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm. Action Statement Profile Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, systematic reviews on the benefits of counseling in general on healthcare outcomes; Grade C observational studies on the effectiveness of interventions for voice rehabilitation. Benefit: Facilitates informed decision making; reduces anxiety; improves awareness of options for rehabilitation. Risk, Harm, Cost: None for counseling. Cost for implementation of voice therapy may be significant, depending on patient’s insurance status. Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit. Value Judgments: Benefits seen in clinical studies from pursuing these options have been extrapolated to a beneficial effect from counseling the patient and increasing awareness. Intentional Vagueness: None. Role of Patient Preferences: Substantial regarding the method and extent of counseling provided. Exclusions: None. Policy Level: Recommendation. References Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #86. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2010; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb86.jsp. Accessed 6/4/12. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. 2011; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-029771.pdf. Accessed 3/28/12. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. 2012; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf. Accessed 3/28/12. Gharib H, Papini E, Valcavi R, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and Associazione Medici Endocrinologi medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. Endocr Pract. Jan-Feb 2006;12(1):63-102. Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. May 10 2006;295(18):2164-2167. Brown RL, de Souza JA, Cohen EE. Thyroid cancer: burden of illness and management of disease. J Cancer. 2011;2:193-199. Husson O, Haak HR, Oranje WA, Mols F, Reemst PH, van de Poll-Franse LV. Health-related quality of life among thyroid cancer survivors: a systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). Oct 2011;75(4):544-554. Stojadinovic A, Shaha AR, Orlikoff RF, et al. Prospective functional voice assessment in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Ann Surg. Dec 2002;236(6):823-832. Soylu L, Ozbas S, Uslu HY, Kocak S. The evaluation of the causes of subjective voice disturbances after thyroid surgery. Am J Surg. Sep 2007;194(3):317-322. Wilson JA, Deary IJ, Millar A, Mackenzie K. The quality of life impact of dysphonia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Jun 2002;27(3):179-182. Jones SM, Carding PN, Drinnan MJ. Exploring the relationship between severity of dysphonia and voice-related quality of life. Clin Otolaryngol. Oct 2006;31(5):411-417. Jeannon JP, Orabi AA, Bruch GA, Abdalsalam HA, Simo R. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. Apr 2009;63(4):624-629. Mendels EJ, Brunings JW, Hamaekers AE, Stokroos RJ, Kremer B, Baijens LW. Adverse laryngeal effects following short-term general anesthesia: a systematic review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2012;138(3):257-264. Roy N, Smith ME, Dromey C, Redd J, Neff S, Grennan D. Exploring the phonatory effects of external superior laryngeal nerve paralysis: an in vivo model. Laryngoscope. Apr 2009;119(4):816-826. Sinagra DL, Montesinos MR, Tacchi VA, et al. Voice changes after thyroidectomy without recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. J Am Coll Surg. Oct 2004;199(4):556-560. Hong KH, Kim YK. Phonatory characteristics of patients undergoing thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 1997;117(4):399-404. Ho TW, Shaheen AA, Dixon E, Harvey A. Utilization of thyroidectomy for benign disease in the United States: a 15-year population-based study. Am J Surg. May 2011;201(5):570-574. Graney D, Flint P. Anatomy of Larynx, Hypopharynx, Trachea, Bronchus, Esophagus. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 1998. Sosa JA, Mehta PJ, Wang TS, Boudourakis L, Roman SA. A population-based study of outcomes from thyroidectomy in aging Americans: at what cost? J Am Coll Surg. Jun 2008;206(3):1097-1105. Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

This month, the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) publishes its latest clinical practice guideline focusing on improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery as a supplement to Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. This month’s journal and a copy of the guideline are now available at http://oto.sagepub.com/.

The following summary presents an outline of the guideline; we encourage all interested parties to read the guideline in its entirety. The intent of this offering is to alert members to the availability of this new multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline so that the complexities of the problem can be fully described and understood. The summary provides an introduction to the topic and the purpose of developing the guideline followed by each of the guideline’s key action statements and related action statement profiles.

For more information about the AAO-HNSF’s other quality knowledge products (clinical practice guidelines and clinical consensus statements), our guideline development methodology, or to submit a topic for future guideline development, visit: http://www.entnet.org/guidelines.

Introduction

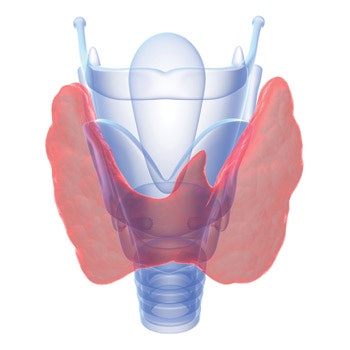

Thyroidectomy (surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland) may be performed for clinical indications that include malignancy, benign nodules or cysts, suspicious findings on fine needle aspiration biopsy, dysphagia from cervical esophageal compression, or dyspnea from airway compression. Other indications for thyroidectomy include multinodular goiter, Hashimoto’s and other types of thyroiditis, and thyromegaly with significant cosmetic compromise. Additional surgery may involve neck dissection or completion thyroidectomy, based on the extent of disease and final pathology results. Surgeons performing thyroidectomy include otolaryngologists and general surgeons.

Thyroid surgery rates have tripled over the past three decades. Between 118,000 and 166,000 patients in the U.S. undergo thyroidectomy each year for benign or malignant disease.1 Thyroidectomy is performed on patients of both genders, but more commonly on women. Thyroid cancer is the most common malignancy of the endocrine system, and the cancer with the fastest-growing incidence among women. It is estimated that 36,550 women and 11,470 men (48,020 total) in the U.S. were diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2011,2 with 56,000 projected in 2012.3 Palpable thyroid nodules occur in three percent to seven percent of the population; ultrasound indicates that the actual prevalence of thyroid nodules is up to 50 percent. On fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), five percent of thyroid nodules are malignant and 10 percent are suspicious. FNAB has increased the identification of malignancy in nodules from 15 percent to 50 percent predominantly due to increased detection of small papillary cancers.4 The incidence of thyroid cancer in the U.S. rose from 3.6 per 100,000 in 1973 to 8.7 per 100,000 in 2002—a 2.4-fold increase.5 It is the fifth most diagnosed cancer in women, whom it affects more than three times more commonly than it does men. Although peak incidence is between ages 45 and 49 in women and 65 and 69 in men, thyroid cancer accounts for 10 percent of all malignancies diagnosed in young people between the ages of 15 and 29.6 Mortality from thyroid cancer remains low at 0.5 per 100,000.5 The overall numbers of thyroid surgery continue to increase: in 2007, U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) statistics indicated that 37.4 thyroidectomies were performed per 100,000 population. Both increased detection and growing U.S. population (from 281 million in 2000 to 309 million in 2010) enable estimates of thyroid surgery in 2012 of between 118,000 and 166,000.

The goals of thyroid surgery remain: complete removal of the abnormal thyroid and any involved lymph nodes, preservation of parathyroid gland function, and maintenance or improvement of voice and swallowing. Reduction in quality of life (QOL) after thyroid surgery is multifactorial, may include the need for lifelong medication, thyroid suppression, radioactive scanning/treatment, temporary and permanent hypoparathyroidism, temporary or permanent dysphonia postoperatively and dysphagia.7-11 Voice disturbance may be identified at least temporarily in up to 80 percent of patients after thyroid surgery, but prevention, evaluation, and management are incompletely defined.8 About one in 10 patients experience temporary laryngeal nerve injury after surgery with longer-lasting voice problems in up to one in 25.12 Although temporary hoarseness is not uncommon in any surgery that involves general anesthesia, the potential for laryngeal nerve injury in thyroid surgery mandates greater concern when hoarseness occurs after this type of procedure.13

The most common site of injury is damage to one or both recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN), which are close to the thyroid gland and are the main nerves that control vocal fold mobility. The other nerves of major interest, and frequently less directly addressed during thyroid surgery, are the bilateral superior laryngeal nerves (SLN), injury to which can impair the ability to change pitch and reduce voice projection.14 Another less common surgical cause for post-thyroidectomy voice change is cervical strap muscle injury.15,16 Non-surgical causes may include laryngeal irritation, edema, or injury from airway management.9

Between 1993 and 2007 the performance of total (over partial) thyroidectomy more than doubled to nearly 40 percent of cases, and that will continue to grow.17 Total (or bilateral) thyroidectomy puts twice the number of SLNs and RLNs at risk. This clinical practice guideline (CPG) seeks to provide guidance to minimize post-thyroidectomy voice impairment in the setting of the increasing number and extensiveness of thyroidectomies being performed by diversely trained and experienced surgeons.

- Thyroidectomy is defined as a surgical procedure performed to partially or completely remove the thyroid gland. This term may include total thyroidectomy, or partial thyroidectomy, which includes subtotal thyroidectomy and hemithyroidectomy.

- Voice outcomes include the patient’s own perceptions of their vocal quality, the perceptions of others, and objective voice-related measurements.

- Vocal folds, also known as the vocal cords, are twin infoldings of mucous membrane covering the upper surface of each vocalis (or thyroarytenoid) muscle, which extend from the midline, anterior attachment to the thyroid cartilage projecting posteriorly to the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage.18 The vocal folds vibrate, modulating the flow of air being expelled from the lungs during phonation. They consist of epithelium and lamina propria overlying the vocalis muscle.

- Vocal fold mobility disorders as used in this document include paresis or hypomobility, which are synonymous with vocal fold weakness, and paralysis, which is immobility of the fold.

- Voice impairment can range from aphonia, which is absence of phonation, to dysphonia, which could include persistent or intermittent breathiness, hoarseness, reduced volume, vocal fatigue, and/or pitch change.

Although thyroidectomy procedures may be performed in all age groups, this guideline is limited to adults (aged 18 and older). In a review of AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from 2003 to 2004, the majority of adult patients (78.8 percent) undergoing thyroid surgery were between 18 and 64 years old, 17.9 percent were between ages 65 and 79 years, and 3.3 percent were 80 years old or older.19

Purpose

As defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), CPGs are “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care, that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.” They are based on a thorough review of the best evidence available at the time of writing, as evaluated by a multi-disciplinary panel with representation by as many stakeholders as possible. CPGs are intended to enhance clinician and patient decision-making by collating current best evidence into an explicit and transparent action plan.20

The purpose of this guideline is to optimize voice outcomes for adult patients aged 18 years or older after thyroid surgery. The target audience is any clinician involved in managing such patients, which includes, but may not be limited to, otolaryngologists, general surgeons, endocrinologists, internists, speech-language pathologists, family physicians and other primary care providers, anesthesiologists, nurses, and others who manage patients with thyroid/voice issues. The guideline applies to any setting in which clinicians may interact with patients before, during, or after thyroid surgery. Children younger than 18 years are specifically excluded from the target population; however, the panel understands that many of the findings may be applicable to this population. Also excluded are patients undergoing concurrent laryngectomy. Although this guideline is limited to thyroidectomy, some of the recommendations may extrapolate to parathyroidectomy as well.

Actions considered by the guideline development group (GDG) were broadly classified into laryngeal examination, voice assessment, nerve management, and interventions. The group agreed that voice outcomes could potentially be improved:

- Preoperatively, with examination of the larynx, baseline preoperative voice assessment, and appropriate counseling and education for realistic expectations;

- Intraoperatively, with targeted communication among the members of surgical team, proper anesthetic preparation including avoidance of laryngeal trauma during intubation and avoidance of paralytic agents where indicated, surgical techniques geared to optimize voice outcomes by preventing injury as well as by recognizing and managing injury, use of adjuvant medications during surgery, and defining a role for intraoperative nerve monitoring; and

- Postoperatively, with baseline postoperative laryngeal examination and voice assessment, setting expectations for recovery, knowing when and to whom to refer, and discussion of options for rehabilitation of voice impairment.

This guideline is intended to focus on quality improvement opportunities judged most important by the GDG. It is not intended to be a comprehensive guide for managing patients undergoing thyroid surgery. In this context, the purpose is to define useful actions for clinicians, regardless of discipline, to improve quality of care and voice outcomes. Conversely, the statements in this guideline are not intended to limit or restrict care provided by clinicians based on the assessment of individual patients.

Although there is evidence to guide management of many aspects of thyroid surgery, there is no evidence-based, multi-disciplinary, CPG that specifically deals with improving voice outcomes. This guideline is warranted because of known practice variations in the care of patients who undergo thyroid surgery and the large impact voice impairment can have on a patient’s QOL and functional health status.

STATEMENT 1. BASELINE VOICE ASSESSMENT:

The surgeon should document assessment of the patient’s voice once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Establish a baseline, improve the detection of preexisting voice impairment, establish expectations about voice outcomes, educating the patient, facilitates shared decision-making. Prioritize the need for preoperative laryngeal assessment and more in-depth voice assessment.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Anxiety, cost of assessment tool, patient and provider time.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: Perception by the GDG of a current underassessment of voice prior to surgery.

- Intentional Vagueness: The proximity of the assessment to the day of surgery is not specified because there was no consensus among the guideline group and there was no data to support the choice of one time-point over another. The group agreed that any change in voice would warrant a new assessment.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Selection of assessment methods.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 2A. PREOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPAIRED VOICE:

The surgeon should examine vocal fold mobility, or refer the patient to a clinician who can examine vocal fold mobility, if the patient’s voice is impaired (as determined by the assessment in Statement 1) and a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Assess mobility of vocal fold, potential diagnosis of invasive thyroid cancer, influence the decision for surgery, extent of surgery, intraoperative technique, preoperative patient counseling, distinguish iatrogenic from disease-related paralysis/paresis.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Misdiagnosis (false positive/ false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Limited.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 2B. PREOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL ASSESSMENT OF THE NON-IMPAIRED VOICE:

The surgeon should examine vocal fold mobility, or refer the patient to a clinician who can examine vocal fold mobility, if the patient’s voice is normal and the patient has (a) thyroid cancer with suspected extrathyroidal extension, or (b) prior neck surgery that increases the risk of laryngeal nerve injury (carotid endarterectomy, anterior approach to the cervical spine, cervical esophagectomy, and prior thyroid or parathyroid surgery), or (c) both, once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Assess mobility of vocal fold, potential diagnosis of invasive thyroid cancer, influence the decision for surgery, extent of surgery, intraoperative technique, preoperative patient counseling, distinguish iatrogenic from disease-related paralysis/paresis.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Misdiagnosis (false positive/false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: Even though the prevalence of preoperative vocal fold paresis is low, the consequence of not knowing this prior to surgery could result in substantial morbidity or mortality. For this reason, the GDG was willing to accept a large number of normal examinations in return for an occasional abnormal finding.

- Intentional Vagueness: The timing of assessment relative to surgery is not stated to allow clinicians flexibility in decision-making, although the guideline development group agreed that the assessment should take place as close to the surgery as possible. The word suspected is used due to the difficulty of identifying extrathyroidal extension through physical exam and imaging.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Limited.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 3. PATIENT EDUCATION ON VOICE OUTCOMES:

The clinician should educate the patient about the potential impact of thyroid surgery on voice once a decision has been made to proceed with thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, RCTs on the value of patient education in general regarding surgery. Grade C, studies on the incidence of voice impairment following thyroid surgery in particular.

- Benefit: Facilitate shared decision making, establish realistic expectations, help patients recognize voice changes postoperatively.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Anxiety.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: Generalize evidence about the benefits of patient education to this circumstance.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Patient can decline information.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 4. COMMUNICATION WITH ANESTHESIOLOGIST:

The surgeon should inform the anesthesiologist of the results of abnormal preoperative laryngeal assessment in patients who have had laryngoscopy prior to thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Allow anesthesiologist to select proper tube, allow anesthesiologist to optimize airway management, identify potential problems with intubation and extubation, plan postoperative care and monitoring, may prevent anesthetic-related voice disturbance.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: None.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: The guideline development group felt that even though the recommendation followed best practice there was a perception the action was not universally performed.

- Intentional Vagueness: Timing of discussion is not specified but should occur before the patient enters the operating room.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 5. IDENTIFYING RECURRENT LARYNGEAL NERVE:

The surgeon should identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve(s) during thyroid surgery. Strong recommendation based on a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, RCTs and retrospective cohort studies.

- Benefit: Optimize voice outcome, protect the RLN, preserve laryngeal function, reduce incidence of RLN injury.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Inadvertent RLN injury, extended operative time, false identification of another structure as the RLN.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: Thyroid surgery limited to the isthmus.

- Policy Level: Strong recommendation.

STATEMENT 6. PROTECTION OF SUPERIOR LARYNGEAL NERVE:

The surgeon should take steps to preserve the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve(s) when performing thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Preserves vocal projection and high frequencies.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: May leave superior pole thyroid tissue.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: The steps taken to preserve the nerve are purposefully not specified in the statement to emphasize the important issue is preserving the nerve, which may or may not be identifiable during surgery. Therefore, it is the attention to the nerve that is important.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 7. INTRAOPERATIVE EMG MONITORING:

The surgeon or their designee may monitor laryngeal electromyography (EMG) during thyroid surgery. Option based on one RCT and observational studies with a balance of benefit versus harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C.

- Benefit: Added information regarding neurophysiologic status of the RLN (specifically when the nerve is injured), potential improved accuracy in nerve identification, potentially avoiding transient/temporary nerve.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: cost of endotracheal tube and probe, capital equipment costs, education of key personnel including anesthesia, nursing, surgeon and technician, misinterpretation (both false positive/false negative), may instill a false sense of security in identifying nerve.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Equilibrium.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Option.

STATEMENT 8. INTRAOPERATIVE CORTICOSTEROIDS:

No recommendation can be made regarding the impact of a single intraoperative dose of intravenous corticosteroid on voice outcomes in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. No recommendation based on observational studies with limitations and a balance of benefit vs. harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade D, observational studies with concerns over methodology and clinical importance.

- Benefit: Uncertain effect on short-term voice improvement or shortening the duration of vocal fold paralysis or paresis.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Hyperglycemia.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Balance of benefit vs. harm.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: No recommendation.

STATEMENT 9. POSTOPERATIVE VOICE ASSESSMENT:

The surgeon should document whether there has been a change in voice between two weeks and two months following thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, and prospective, observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, cohort studies on the prevalence and duration of voice changes after thyroid surgery and the underreporting of voice changes if not specifically sought.

- Benefit: Identification of significant voice impairment and early institution of counseling and/or voice rehabilitation; avoidance of patient anxiety.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Cost of assessment tools/examinations.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: The guideline development group believes that post-operative voice assessment is not being performed universally, in the identified time frame.

- Intentional Vagueness: The documentation time is stated as between two weeks and two months because there is no evidence on the optimal time, but the GDG suggests that the evaluation should be late enough to overcome transient postoperative changes but early enough to allow effective intervention.

- Role of Patient Preferences: No role in documenting the outcome, but a significant role in the choice and extent of outcome assessment.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 10. POSTOPERATIVE LARYNGEAL EXAMINATION:

Clinicians should examine vocal fold mobility or refer the patient for examination of vocal fold mobility in patients with a change in voice following thyroid surgery (as identified in Statement 9). Recommendation based on preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, QOL data, early intervention data, diagnostic maneuver.

- Benefit: Detect nerve injury, gain information regarding prognosis, institute rehabilitation as needed.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: misdiagnosis (false positive/ false negative), cost of examination, patient discomfort, resources, access, anxiety, by restricting this recommendation to only patients with a voice change some nerve injuries may be missed.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: The timing of the examination is not specified, but should occur expeditiously after the identification of a voice change, as identified in Statement 9.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Moderate, based on patient self-perception of voice postoperatively, based on type of examination of larynx, based on physician determination and patient consent.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 11. OTOLARYNGOLOGY REFERRAL:

The clinician should refer a patient to an otolaryngologist when abnormal vocal fold mobility is identified after thyroid surgery. Recommendation based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade C, before- and after- studies showing voice improvement after surgical intervention.

- Benefit: Awareness of the opportunities for early surgical intervention, confirmation of the laryngeal findings, determination of appropriate treatment plan, facilitates shared-decision making, facilitates coordination with speech-language pathologist in care of patient.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: Cost, time, access.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: None.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: None.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

STATEMENT 12. VOICE REHABILITATION:

Clinicians should counsel patients with voice change or abnormal vocal fold mobility after thyroid surgery on options for voice rehabilitation. Recommendation based on systematic reviews and observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.

Action Statement Profile

- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Grade B, systematic reviews on the benefits of counseling in general on healthcare outcomes; Grade C observational studies on the effectiveness of interventions for voice rehabilitation.

- Benefit: Facilitates informed decision making; reduces anxiety; improves awareness of options for rehabilitation.

- Risk, Harm, Cost: None for counseling. Cost for implementation of voice therapy may be significant, depending on patient’s insurance status.

- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponderance of benefit.

- Value Judgments: Benefits seen in clinical studies from pursuing these options have been extrapolated to a beneficial effect from counseling the patient and increasing awareness.

- Intentional Vagueness: None.

- Role of Patient Preferences: Substantial regarding the method and extent of counseling provided.

- Exclusions: None.

- Policy Level: Recommendation.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #86. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2010; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb86.jsp. Accessed 6/4/12.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. 2011; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-029771.pdf. Accessed 3/28/12.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. 2012; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf. Accessed 3/28/12.

- Gharib H, Papini E, Valcavi R, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and Associazione Medici Endocrinologi medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. Endocr Pract. Jan-Feb 2006;12(1):63-102.

- Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. May 10 2006;295(18):2164-2167.

- Brown RL, de Souza JA, Cohen EE. Thyroid cancer: burden of illness and management of disease. J Cancer. 2011;2:193-199.

- Husson O, Haak HR, Oranje WA, Mols F, Reemst PH, van de Poll-Franse LV. Health-related quality of life among thyroid cancer survivors: a systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). Oct 2011;75(4):544-554.

- Stojadinovic A, Shaha AR, Orlikoff RF, et al. Prospective functional voice assessment in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Ann Surg. Dec 2002;236(6):823-832.

- Soylu L, Ozbas S, Uslu HY, Kocak S. The evaluation of the causes of subjective voice disturbances after thyroid surgery. Am J Surg. Sep 2007;194(3):317-322.

- Wilson JA, Deary IJ, Millar A, Mackenzie K. The quality of life impact of dysphonia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. Jun 2002;27(3):179-182.

- Jones SM, Carding PN, Drinnan MJ. Exploring the relationship between severity of dysphonia and voice-related quality of life. Clin Otolaryngol. Oct 2006;31(5):411-417.

- Jeannon JP, Orabi AA, Bruch GA, Abdalsalam HA, Simo R. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. Apr 2009;63(4):624-629.

- Mendels EJ, Brunings JW, Hamaekers AE, Stokroos RJ, Kremer B, Baijens LW. Adverse laryngeal effects following short-term general anesthesia: a systematic review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2012;138(3):257-264.

- Roy N, Smith ME, Dromey C, Redd J, Neff S, Grennan D. Exploring the phonatory effects of external superior laryngeal nerve paralysis: an in vivo model. Laryngoscope. Apr 2009;119(4):816-826.

- Sinagra DL, Montesinos MR, Tacchi VA, et al. Voice changes after thyroidectomy without recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. J Am Coll Surg. Oct 2004;199(4):556-560.

- Hong KH, Kim YK. Phonatory characteristics of patients undergoing thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 1997;117(4):399-404.

- Ho TW, Shaheen AA, Dixon E, Harvey A. Utilization of thyroidectomy for benign disease in the United States: a 15-year population-based study. Am J Surg. May 2011;201(5):570-574.

- Graney D, Flint P. Anatomy of Larynx, Hypopharynx, Trachea, Bronchus, Esophagus. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Richardson M, Schuller D, eds. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 1998.

- Sosa JA, Mehta PJ, Wang TS, Boudourakis L, Roman SA. A population-based study of outcomes from thyroidectomy in aging Americans: at what cost? J Am Coll Surg. Jun 2008;206(3):1097-1105.

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.