How the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Changing the Approach to Global Surgery

As the COVID-19 pandemic arose in the spring of 2020, many surgical humanitarian organizations were forced to cancel trips that had been scheduled for months or even years.

Brianne Barnett Roby, MD, Children’s Minnesota/University of Minnesota, member of the AAO-HNSF Humanitarian Efforts Committee and Pediatric Otolaryngology Education Committee

Melesse Gebeyehu, MD, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia

Rajanya Petersson, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University

Dr. Gebeyehu, surgeon, and Dr. Petersson, “assisting” or teaching in Ethiopia.

Dr. Gebeyehu, surgeon, and Dr. Petersson, “assisting” or teaching in Ethiopia.

One such group is Children’s Surgery International (CSI), an organization whose mission is to help provide care to children in under-resourced locations through training local surgeons and medical providers in an effort to achieve sustainability. Organizations such as this are increasingly focusing on teaching local surgeons directly, as well as anesthesia teams, pediatric teams, and nursing teams in the operating room and the wards. It is clear that the education of teams around the world should continue, even if we cannot physically travel. Several organizations have created interactive, tele-education lecture series for local surgeons on topics ranging from cleft lip repair to thyroglossal duct cyst removal. Increased communication with global surgeons has fostered challenging case discussions, with photographs, imaging, and other background information shared between local surgeons and volunteer surgeons from various organizations. Collaborating with talented local surgeons in this manner reveals that they seek continued education and interaction on a continued basis, and not just during short, in-person humanitarian trips.

This does however require a foundation and vision for a model of education, for which many humanitarian organizations have been dedicated. For example, at the Bahir Dar, Ethiopia site, several local surgeons have trained with CSI surgeons twice a year during trips beginning in 2016. Every effort is made on these visits not to undermine the local surgeons and providers with the eventual goal that the group will not need to return once training is completed. For example, during screening, the local surgeons are at the forefront of assessing patients. The local surgeons perform pre- and postoperative discussion and are active on daily rounds. With consistent training, skills can be checked off for various procedures. At this site, the local teams are motivated and passionate about building programs involving cleft lip and palate surgery within their growing otolaryngology and head and neck surgery programs. These are ideals that are shared by many surgeons who participate in humanitarian missions, and building these collaborations are mutually beneficial to all involved. By the end of the last two trips to Bahir Dar in the spring and fall of 2019, prior to the pandemic cancelling the spring 2020 trip, local surgeons were able to complete cleft lip and palate procedures on their own with minimal supervision from CSI surgeons.

One surgeon in Bahir Dar, Melesse Gebeyehu, MD, had spoken of being grateful for the training he had received but was dismayed that he could not often use his skills in between CSI education trips because patients would seek care from other foreign groups also providing care at other times throughout the year. This is not an uncommon story heard from local surgeons around the world. With travel halted during most of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he was able to do several cleft lip and palate cases throughout the year. He sent pre- and postoperative photographs to CSI surgeons for review and feedback and demonstrated excellent results achieved without direct supervision. Unexpectedly, this showed CSI’s education model was working at this site and provided a silver lining for this challenging year.

But Dr. Gebeyehu also provided the following summarized perspective.

"Because of the high prevalence of cleft cases and competing elective cases put on hold during the pandemic, there are still factors that limit what they can do. There are very few otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons, they face a poor healthcare systems and infrastructure, and there are limited medical supplies to address this type of specialized care. These factors continue to challenge and compromise the care they are able to give to cleft patients."

As surgical humanitarian organizations start to discuss returning to travel, it is worth considering that large teams of healthcare providers from the United States travelling to various locations around the world may become a thing of the past. It should be considered that it may be years before many countries receive the COVID-19 vaccine, continuing to restrict travel.

In addition, this would change the way traditional surgical humanitarian trips operate.

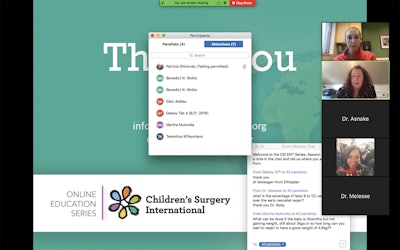

A recent virtual lecture presented by Brianne Barnett Roby, MD, to surgeons in Ethiopia, Gambia, Liberia, and Tanzania.

A recent virtual lecture presented by Brianne Barnett Roby, MD, to surgeons in Ethiopia, Gambia, Liberia, and Tanzania.

The changes due to COVID-19 may help push many NGOs with a teaching mission to advance their goals faster and increase their collaborations with host countries remotely. This continued education of local teams throughout the year, most importantly, allows patients needing care in these countries to receive treatment whether or not an NGO team can travel there. At a time when many groups are trying to achieve sustainability, we have examples showing that the training of local surgeons can be achieved in a relatively short period of time and continued remotely, thereby allowing for care to be delivered without the presence of a foreign surgical humanitarian group. In addition, funds could be diverted to increasing supplies and resources rather than the cost of travel of large teams. This pandemic highlights the need for education-minded surgical groups in order to achieve sustainability in under resourced areas of the world, so that children can receive needed surgical care regardless of the situation preventing travel.