An Evidence-Based Guide to Chronic Aspiration

Treating chronic aspiration in adults requires a personalized, multidisciplinary approach to preserve quality of life and prevent life-threatening complications.

Apoorva T. Ramaswamy, MD, on behalf of the Airway and Swallowing Committee

Population-based studies suggest that oropharyngeal dysphagia affects up to 30%–40% of patients with stroke, 60%–80% of those with advanced Parkinson’s disease, and over 50% of residents in long-term care facilities. Aspiration pneumonia is estimated to account for 5% to 24% of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) cases in adults, especially among older patients.¹ Silent aspiration, often unrecognized without objective evaluation, contributes substantially to disease burden.² In HNC survivors, up to 45% experience chronic dysphagia,³ and 24% develop aspiration pneumonia within five years of chemoradiation—with a 30-day mortality exceeding 30% following hospitalization.⁴

Effective care requires multidisciplinary evaluation, individualized intervention, and close monitoring of therapeutic outcomes.

Goals of Care

Goals of care discussions are essential in managing adults with chronic aspiration, particularly those with advanced age, neurodegenerative diseases, head and neck cancer, or high frailty scores. Marik and Kaplan emphasized the need for individualized care plans in older patients with dysphagia, as aggressive medical treatment can often conflict with patient goals and quality of life.⁵ Similarly, Ocrospoma and Restrepo noted that older ICU patients with severe aspiration pneumonia often experience significant functional decline and limited survival, reinforcing the value of early goals of care planning.⁶ Kuttner advocated aligning interventions such as enteral feeding or tracheostomy with the patient's overall prognosis, cognitive status, and life expectancy.⁷ Gastrostomy tubes (G-tubes) may reduce aspiration from oral intake but do not prevent aspiration of saliva or reflux, and studies show mixed impact on survival or quality of life in frail older adults. Nutritional conversations should be approached with nuance. For some patients, risk-tolerant oral feeding may offer dignity and enjoyment. In others, G-tube placement may be a bridge or a palliative strategy. Sharoni et al. emphasized education and shared decision-making in Parkinson's patients with severe dysphagia, encouraging caregivers to explore all options within the context of values and goals.⁸

Diagnostic Workup

Accurate evaluation of chronic aspiration begins with clinical history and symptom screening, but instrumental diagnostics remain essential due to the high prevalence of silent aspiration, particularly in older adults. The primary tools include fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) and videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS).

Working with a skilled speech language pathologist (SLP) throughout the workup and therapy plan for a dysphagia patient is critical, particularly an SLP with dysphagia specialization. An SLP who considers patient’s goals of care in dietary recommendations and is well-versed in evidence based testing and therapy is essential. During this diagnostic step, an SLP is able to identify functional deficits and evaluate the efficacy of compensatory strategies. Meanwhile, a surgeon uses these assessments to evaluate anatomical deficits and opportunities for medical or surgical interventions.

FEES, a flexible endoscopic exam of the pharynx and larynx during ingestion of various textures of food offers bedside feasibility, excellent visualization of secretion pooling, and no radiation exposure. However, it does not permit evaluation of the oral or esophageal phase. VFSS, a fluoroscopic study of the head, neck and chest during swallowing of various textures of barium, by contrast, provides comprehensive imaging across all swallow phases and is considered the gold standard for aspiration detection—especially silent aspiration. In a comparative study, VFSS detected silent aspiration in up to 38% of cases missed by FEES.⁹ FEES however is essential for functional examination of laterality, allowing providers to understand pharyngeal strength changes, velopharyngeal function and vocal fold mobility. An experienced clinician will be able to identify the appropriate test for a patient, and the correct answer may be both, depending on the circumstances. Evidence based standards for completion of FEES and VFSS, while important, are outside the scope of this overview.

Emerging diagnostics such as cough testing, nasometry, high-resolution pharyngeal manometry and impedance-pH testing are increasingly used to evaluate esophageal and reflux-related aspiration. Multidisciplinary team assessments significantly improve diagnostic accuracy, particularly when combining imaging with functional assessment and nutrition evaluation.10,11

Nonsurgical Interventions

Nonsurgical interventions are foundational to managing chronic aspiration. Speech and language therapy remains a core intervention and collaboration with an SLP with expertise in dysphagia is essential to management of this complex population.² As mentioned above, an experienced SLP will use the diagnostic step of the workup to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the patient’s swallow with various textures, guiding the patient with any compensatory techniques that may help. Additionally, they will assess functional deficits and attempt to address them with a therapeutic plan that will address reinforcement of compensatory techniques in addition to coordination and strengthening of various structures, as needed.

Dietary modifications such as texture adaptation and bolus volume control remain widely used. Chen et al. found these reduced aspiration risk when paired with supervised meals.2 Compensatory techniques—chin tuck, head turn—have proven effective in controlled studies. Although texture-modified diets are widely recommended, they are not without risks. O'Keeffe reported that thickened liquids are poorly tolerated, leading to reduced fluid intake and increased risk of dehydration in older adults.12 Modified foods may also contribute to inadequate caloric intake and malnutrition, particularly in frail or cognitively impaired patients. Compliance is often low due to dissatisfaction with taste and texture.13 Recent research by Shimizu et al. confirmed that patients on pureed or liquidized diets during rehabilitation reported significantly lower quality of life scores.14 Common issues include social withdrawal, lack of mealtime satisfaction, and reduced autonomy. These findings underscore the need for personalized nutritional planning that weighs both aspiration risk and the psychosocial impact of dietary restrictions.

Other nonsurgical interventions are more generalizable to the dysphagia population as a whole. Oral hygiene is one such key component. Multiple reviews found that poor oral care correlates with increased pneumonia incidence.15,16 Daily brushing and caregiver education significantly lower this risk, especially in older and institutionalized populations. Boler's implementation study linked structured oral care to reduced hospital-acquired pneumonia.17 Other routine clinical practices such as upright positioning during and after meals, slow feeding, and clear environmental cues can reduce aspiration events. Loeb et al. demonstrated that such compensatory strategies, though low-tech, reduce pneumonia when applied consistently.18 Daily monitoring of vital signs may allow earlier identification of aspiration-related complications, supporting timely intervention.19

Pharmacologic prevention of aspiration pneumonia is controversial. A systematic review by El Solh et al. reported mixed results: ACE inhibitors may reduce pneumonia by improving swallow reflex in stroke survivors, but prophylactic antibiotics were ineffective and potentially harmful.20 Capsaicin showed some promise in stimulating cough reflex but lacks broad validation. Overall, nonsurgical strategies must be personalized, regularly reassessed, and implemented with interprofessional support.

Surgical Interventions

Surgical interventions for patients with chronic dysphagia vary in invasiveness and risk profile. Decisions about the potential surgical interventions depend on history, physical exam and objective testing in addition to extensive patient counseling about risks, benefits and goals of care. For a patient without life-threatening dysphagia, options depend on deficits.

For example, oral dysphagia can include deficits of the lips, cheek and tongue. Correction of facial muscle paralysis may be necessary for oral control and improved oral competence, in the appropriate patient. Others may benefit from simple lip augmentation to improve oral competence in a patient with marginal mandibular nerve damage. Pharyngeal dysphagia may affect the palate function, and velopharyngeal flap, or pharyngeal augmentation or an obturator may be appropriate. In patients with severe issues of efficiency in the pharynx, perhaps interventions at the level of the pharyngoesophageal segment may be most appropriate, with dilation, chemical denervation or cricopharyngeal myotonic being options. A patient may also have vocal fold immobility or glottic incompetence, in which case a vocal fold augmentation or thyroplasty may be appropriate treatments. The need for customization based on FEES and VFSS results becomes apparent as care for these patients may require a combination of interventions.

Surgical interventions for life-threatening dysphagia are reserved for patients with severe, intractable aspiration that is unresponsive to conservative management who are counseled about the risks and benefits of each option and who are capable of having an in-depth discussion about the importance of oral intake for their goals of care.21

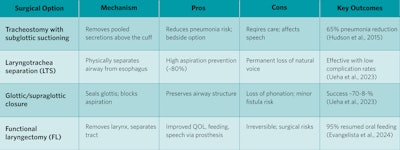

Tracheostomy with subglottic suctioning is a supportive strategy used to reduce secretion burden. Coffman et al. showed significant reduction in aspirated volume using proximal suction tracheostomy tubes.22 Hudson et al. found a 65% reduction in pneumonia with subglottic suction tubes post-cardiac surgery.23 This can be used as a temporary measure and can be reversed based on changes to clinical status. Laryngotracheal separation (LTS), glottic closure, and functional laryngectomy on the other hand are definitive strategies that involve separation of the respiratory and swallowing functions of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Thus, these interventions will change communication and are associated with increased surgical risk. Functional laryngectomy is the best studied. Evangelista et al. demonstrated that functional laryngectomy significantly improved oral intake, speech, and QOL in HNC survivors.24

Table 1. Subglottic suctioning, separation, supraglottic closure and laryngectomy

Conclusion

Adult chronic aspiration requires a structured, multidisciplinary strategy. Diagnostic tools, behavioral modifications, and surgical interventions must be tailored to individual goals. Care planning that integrates early goals of care discussions improves patient satisfaction and outcomes.

References

- Almirall J, Boixeda R, de la Torre MC, Torres A. 2024. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Aspiration Pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 45: 621-625. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1793907.

- Chen S, Kent B, Cui Y. 2021. Interventions to prevent aspiration in older adults with dysphagia living in nursing homes: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 21: 429. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02366-9.

- Hutcheson KA, Nurgalieva Z, Zhao H, Gunn GB, Giordano SH, Bhayani MK, Lewin JS, Lewis CM. 2019. Two-year prevalence of dysphagia and related outcomes in head and neck cancer survivors: An updated SEER-Medicare analysis. Head Neck 41: 479-487. doi: 10.1002/hed.25412.

- Xu B, Boero IJ, Hwang L, Le QT, Moiseenko V, Sanghvi PR, Cohen EE, Mell LK, Murphy JD. 2015. Aspiration pneumonia after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer 121: 1303-11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29207.

- Marik PE, Kaplan D. 2003. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest 124: 328-36. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.328.

- Ocrospoma S, Restrepo MI. 2024. Severe aspiration pneumonia in the elderly. J Intensive Med 4: 307-317. doi: 10.1016/j.jointm.2023.12.009.

- Kuttner C. 2023. "Goals of Care and Prevention." In Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine: A Guide for Practitioners, pp. 183-195. Springer.

- Sharoni SKA, Minhat HS, MZ, Nor Afiah, Anisah B. 2015. Preventive care for aspiration pneumonia: a case study of an elderly with Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 2: 88-98.

- Giraldo-Cadavid, LF, Leal-Leaño, LR, Leon-Basantes, GA, Bastidas, AR, Garcia, R, Ovalle, S and Abondano-Garavito, JE (2017), Accuracy of endoscopic and videofluoroscopic evaluations of swallowing for oropharyngeal dysphagia. The Laryngoscope, 127: 2002-2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26419

- Eisenstadt ES. 2010. Dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia in older adults. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 22: 17-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00470.x.

- Perticone ME, Manti A, Luna CM. 2024. Prevention of Aspiration: Oral Care, Antibiotics, Others. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 45: 709-716. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1793812.

- O'Keeffe ST. 2018. Use of modified diets to prevent aspiration in oropharyngeal dysphagia: is current practice justified? BMC Geriatr 18: 167. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0839-7.

- Luis DA, Izaola O, Prieto R, Mateos M, Aller R, Cabezas G, Rojo S, Terroba C, Martín T, Cuéllar L. 2009. Effects of a diet with products in texture modified diets in elderly ambulatory patients. Nutr Hosp 24: 87-92.

- Shimizu A, Yamaguchi K, Tohara H. 2024. Impact of pureed and liquidised diets on health-related quality of life scores in older patients during postacute rehabilitation: A pilot study. J Hum Nutr Diet 37: 227-233. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13250.

- Santos JMLG, Ribeiro Ó, Jesus LMT, Matos MA. C. 2021. Interventions to Prevent Aspiration Pneumonia in Older Adults: An Updated Systematic Review. J Speech Lang Hear Res 64: 464-480. doi: 10.1044/2020_jslhr-20-00123.

- Pássaro L, Harbarth S, Landelle C. 2016. Prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia in non-ventilated adult patients: a narrative review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 5: 43. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0150-3.

- Boler SJ. "Implementation of an Oral Hygiene Protocol for Adults Patients on Acute Care Units." (2021).

- Loeb MB, Becker M, Eady A, Walker-Dilks C. 2003. Interventions to prevent aspiration pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 1018-22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51318.x.

- Yoshimatsu Y, Ohtake Y, Ukai M, Miyagami T, Morikawa T, Shimamura Y, Kataoka Y, Hashimoto T. 2024. "Diagnose, Treat, and SUPPORT". Clinical competencies in the management of older adults with aspiration pneumonia: a scoping review. Eur Geriatr Med 15: 57-66. doi: 10.1007/s41999-023-00898-4.

- El Solh AA, Saliba R. 2007. Pharmacologic prevention of aspiration pneumonia: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 5: 352-62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.005.

- Ueha R, Magdayao RB, Koyama M, Sato T, Goto T, Yamasoba T. 2023. Aspiration prevention surgeries: a review. Respir Res. England. doi: 10.1186/s12931-023-02354-0 (Corrected)

- Coffman HM, Rees CJ, Sievers AE, Belafsky PC. 2008. Proximal suction tracheotomy tube reduces aspiration volume. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138: 441-445. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.013.

- Hudson JKC, et al. Impact of Subglottic Suctioning on the Incidence of Pneumonia After Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Observational Study Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia, Volume 29, Issue 1, 59 - 63

- Evangelista L, Nativ-Zeltzer N, Bewley A, Birkeland AC, Abouyared M, Kuhn M, Cates D, Farwell DG, Belafsky P. 2024. Functional Laryngectomy and Quality of Life in Survivors of Head and Neck Cancer With Intractable Aspiration. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 150: 335-341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2024.0049.